Why Groundwater Is Running Out in the Panhandle

Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images

Juan Rico works in an cotton field that is watered by an underground irrigation system July 27, 2011 near Hermleigh, Texas.

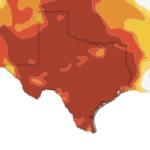

The Texas Panhandle’s corn crops are greener now than they have been in many months. Recent rainfall has given this season’s crops a new lease on life. But, corn crops thirty years from now might not be so lucky. The rapid depletion of the Panhandle’s groundwater supplies could dramatically alter the character of agriculture in the region.

A new study on groundwater depletion in the Central Valley of California and the High Plains Region has placed most of the blame on agriculture irrigation practices. Researchers at the University of Texas claim that the Texas Panhandle will be unable to sustain irrigated agriculture within the next thirty years if current patterns of groundwater use continue.

“Current rates of replenishment in the Panhandle are very low and we are basically pulling out water faster than it is being replenished,” says Dr. Bridget Scanlon, senior research scientist at The University of Texas at Austin’s Bureau of Economic Geology. “It’s just like a bank. If you withdraw money faster than you deposit money, you will eventually run out. The groundwater depletion rate in the northern Texas panhandle is now at least ten times its recharge rate.”

And the Central Valley of California faces a similar situation.

In that region, farmers in the early twentieth century began to meet their crop irrigation needs with groundwater supplies. Heavy use of these resources subsequently led to dramatic drops in groundwater levels. Some places witnessed record four hundred-foot declines. The construction of dams, canals, and reservoirs beginning in the 1930s saw the return of as much as three hundred feet to some groundwater supplies. But according to Scanlon’s research team, increasing irrigation demand since the 1950s has offset these gains by more than one hundred feet.

In response, the Sunshine State has turned to groundwater banking (the storing of excess surface water in natural aquifers) as a possible solution. Two to three cubic kilometers of water are currently stored in California’s groundwater banks, but Scanlon claims that these efforts can be further expanded.

“California is expanding its water banking practices more but it all depends on how much water is available to store in those banks,” said Scanlon.

Unfortunately, groundwater banking doesn’t seem to be an option for the Texas Panhandle.

“There is very little water available to bank in the Texas Panhandle. In California they are diverting water from the north, where it’s humid, to the south, where it’s arid. Unlike Texas, they have extensive infrastructure that was built in the 50s and 60s to divert water this way,” said Scanlon.

If groundwater levels were to drop to the point of no return, farmers might be forced to abandon their traditional irrigated crops and adopt non-irrigated crops such as sorghum instead. Such a shift could create tremendous economic challenges for Texas. Non-irrigated crops tend to produce half the yield of irrigated crops and are particularly fragile in drought.

Sheyda Aboii is an intern with StateImpact Texas.