Evaporation, the Unseen Reservoir-Killer

EPA/LARRY W. SMITH /LANDOV

Dried up mud from the lake bottom at Lake Arrowhead State Park near Wichita Falls, Texas, September 2013.

Even if Rains Return, Climate Change Still Puts Texas Water Supplies at Risk

After years of drought, the city of Wichita Falls in North Texas is going to Stage 4 water restrictions this week, which bans all outdoor watering: No car washes. No more city water for golf courses. And no watering your lawn, of course. It’s the first time the city has moved to this stage, declaring a “drought disaster.”

While a lack of rainfall is certainly to blame for the sorry state of reservoirs in the region, it isn’t the only culprit. Evaporation has also played a big part in making the drought so destructive.

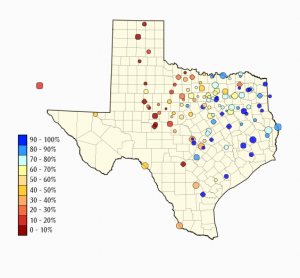

Map by Texas Water Development Board

Reservoir levels across the Western half of Texas remain dangerously low.

A typical year in Wichita Falls will see around 28 days with temperatures of a hundred degrees or higher. In 2011, they had 100 days over 100 degrees.

“Think about that for a minute,” Rusell Schreiber, Public Works Director, said while announcing the new restrictions this week. “That’s over three months of temperatures over a hundred degrees. One-fourth of the entire year.”

All that heat leads to more evaporation in the large, shallow reservoirs of North and West Texas. And it’s not limited to that region. Last year, the Highland Lakes, reservoirs for the city of Austin, lost more water to evaporation than the entire city used from them over the whole year.

Using large reservoirs for water supply allows Texas to capture large amounts of water. But it also creates a vulnerability.

Victory Murphy, Climate Program Manager with the National Weather Service Southern Region, ran down the numbers for us. While the several decades after reservoirs were built in West Texas were relatively cool and wet, it didn’t last. “That flipped in 2000, and temperatures rebounded to above normal,” Murphy says. “The increase in water lost to evaporation had to have skyrocketed. The numbers speak for themselves.”

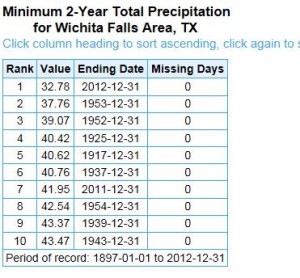

As you can see in the graphs below, precipitation has fallen in the region of Wichita Falls while evaporation has risen rapidly:

The same is true of other reservoirs across West Texas:

For Wichita Falls and other parts of West Texas and the panhandle, having back-to-back two of the hottest and driest years on record has created a massive water deficit. “Obviously, that’s never happened before” in the recorded history, Murphy says. “It’s a double-whammy.”

- This graph shows from 2011-2012, Wichita Falls had its lowest consecutive calendar year rainfall in recorded history.

The combined levels of the two reservoirs serving Wichita Falls, Lakes Arrowhead and Kickapoo, are now at 30 percent. They’re continuing to drop, about a percent each month. (Austin isn’t far off, with its reservoirs at a combined 36 percent of capacity).

The City of Wichita Falls, anticipating the continued drop, adopted the template for the new Stage 4 restrictions in June. They’ll go into effect Saturday. “It is nothing short of a natural disaster that we’re dealing with,” said Darron Keiker, Wichita Falls’ City Manager.

How the community deals with the crisis could provide lessons for other cities that face similar situations in the not-so-distant future. The city points out it has pushed for conservation, saving 2-3 billion gallons so far this year, and cutting their water use in half this summer. While the city is involved in an emergency pipeline project, their lead strategy comes down to conservation: one of the big projects is to reuse wastewater for the drinking water supply.

It has also stepped up enforcement of water restrictions, encouraging citizens to call in reports of water waste and ticketing violators on the first offense. “We’re past the stage for warnings,” Mayor Glenn Barnham said while announcing Stage 4 this week.

While rains may one day return, there is a strong likelihood of higher temperatures in the future due to manmade climate change. That worries climate-watchers like Murphy. If precipitation does return to normal, it may not be enough for the Western half of the state that relies on large surface reservoirs.

“If we have, over a long-term period, one to two degrees of warming [over the next few decades], that is going to lead to more evaporation and more stress on surface water supplies,” Murphy says, pointing to the research of state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon and to the National Climate Assessment. “Even if average rainfall stays the same.”