As Disposal Wells Age, The Risk of Stronger Quakes Grows

Slide Presented by Art McGarr, USGS at the Fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

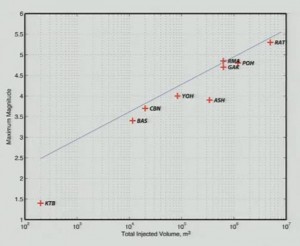

A slide presented by Art McGarr with the USGS, shows a link between the amount of fluid injected into disposal wells and the strength of earthquakes associated with those wells.

There’s already a general scientific consensus that the disposal wells used to store waste deep underground from drilling and hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) can cause earthquakes. But researchers are going into a little more detail about the relationship between quakes and wells at this week’s meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

At a panel discussion Wednesday, three prominent seismologists presented their recent work. One of them was Art McGarr, of the US Geological Survey’s Earthquake Science Center. He’s been looking at whether the amount of fluid stored in a disposal well affects the strength of an earthquake.

His answer: it does.

“I think we’re at the point when, if you tell me that you want to inject a certain amount of waste water, for example a million cubic meters for a particular activity, I can tell you that the maximum magnitude is going to be five (on the Richter scale) or less. I emphasize or less,” McGarr said in his presentation.

The findings contradict the notion that the rate at which fluid is injected in a disposal well impacts the chance of quakes, but it raises another concern. If the findings are correct, they mean the longer a disposal well is injected with fluid, the greater the likelihood of a stronger quake. That means that older wells still in use across Texas and the rest of the country could be growing more and more prone to producing larger earthquakes.

“With time, as an injection activity continues, so will the seismic hazard as measured by the maximum magnitude,” said McGarr at the close of his presentation.

Two other scientists also spoke. Austin Holland, a research seismologist with the Oklahoma Geological Survey, presented work that linked hydraulic fracturing — and not just disposal wells — to earthquakes.

Cliff Frolich, Associate Director of the Institute for Geophysics at University of Texas at Austin, showed work that could link specific Texas earthquakes to drilling operations, including wells.

While the findings had clear policy implications, the panelists were reluctant to address what regulators could do to lessen the risk of earthquakes. One panelist noted that regulation was difficult due to the strength of the oil and gas lobby.

“We’ve made some recommendations, but the regulations become a lot more challenging because, of course, the oil and gas industry has a significant lobby and an interest in providing domestic energy,” Austin Holland said in response to a question submitted online from StateImpact Texas.

Holland also noted that Oklahoma Geological Survey is not a regulatory body.

UT’s Cliff Frolich added that any regulations should take into account whether there are large populations near the site of a disposal well.

“In West Texas, you could have a large earthquake and it wouldn’t affect people very seriously because population is low. A medium-sized earthquake in Dallas-Fort Worth could be serious,” said Frolich.

One final takeaway? You may be hearing more about manmade earthquakes in the future.

“The future probably holds a lot more reported induced earthquakes as the gas boom expands more and more in the coming years,” said the US Geological Survey’s Art McGarr.