Permafrost Melting Faster Than Expected in Antarctica

Dr. Joseph Levy / The University of Texas Institute for Geophysics

Research team member Jim O'Connor of the USGS inspects a block of ice calved off the Garwood Valley ice cliff.

New Research Shows Melting at Rates Comparable to the Arctic

Unlike the Arctic Circle up north, where once-permanent sea ice began melting and miles of permafrost began thawing decades ago, the ground ice in Antarctica’s Garwood Valley was generally considered stable. In this remote polar region near the iceberg-encrusted Ross Sea, temperatures actually became colder from 1986 to 2000, then stabilized, while the climate in much of the rest of the world warmed during that same period.

But now, the ice in Antarctica is melting as rapidly as in the Arctic.

That’s not because temperatures are rising. A team of researchers has discovered that increased solar radiation is thawing ground ice in Garwood Valley at an accelerated rate, disrupting normal seasonal ice patterns.

The cause of the increased solar radiation is, for now, uncertain, although it is related to changes in weather patterns. More research will be required to determine why it is happening.

“I’m a geologist—I look down,” explained Joseph Levy, one of two University of Texas at Austin scientists on the research team and co-author of the research paper in Scientific Reports. “The next step is to figure out what’s driving this change in sunlight patterns. It’s going to involve working with meteorologists and climate modelers.”

Antarctica is predicted to warm during the coming century. As a result, the ground ice could melt even more quickly, which would cause more serious sinking and buckling of the landscape.

Few creatures will notice the collapse of these barren landscapes, and the ones that will are mostly microscopic. The Garwood Valley is home to microorganisms, lichens, and algal mats (thin layers of algae and cyanobacteria that are found in the continent’s seasonal streams). Its top predator, according to Levy, is a nematode—a roundworm that is only a millimeter long. But this ancient, almost untouched part of the world has surprising scientific value.

“What makes Antarctica work, and what makes science there important, is not that it’s exotic and far away, but that it tells us fundamental things about how biological systems work, and how the earth system works,” Levy said. “If you want to understand how organisms are going to respond to climate change—whether they are people, crops, or livestock—[then] a good thing to do is to look at the simplest organism you can find, like a nematode [or] an algal mat, and ask, ‘How is this creature adapting?’”

Levy spends about two months* every year in Antarctica’s dry valleys, documenting how they are changing. When he arrives in October, temperatures are around -22 degrees Fahrenheit. It is so cold that almost everything freezes— food, batteries, electronics, beer, etc. The scientists have to zip their laptops inside their parkas to warm them up enough to operate. Antarctica’s harsh conditions are the earth’s best approximation of life in another cold, dry place that Levy studies: Mars.

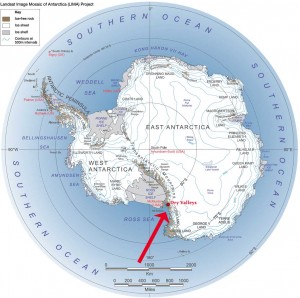

Landsat Image Mosaic of Antarctica.

Garwood Valley lies within the McMurdo Dry Valleys region of Antarctica.

Despite the challenges, Levy says the work is exciting, and the location is exotic. To get there, the research team takes a regular commercial airliner to New Zealand. From there, they board a U.S. military plane that flies them to McMurdo Station, a U.S. research center located on an island in the Ross Sea. Then, the team is flown by helicopter to Garwood Valley. During the Antarctic summer, they are among approximately 50 people living and conducting research in an area the size of Delaware.

“You’re alone with nature, and you can really explore to your heart’s content,” Levy said. “You can run your experiments without fear of interference, without worry about it getting dark. In the summer, it’s light 24 hours a day. It’s a place where you wake up in the morning, you have a question, and you go out and answer it.”

He describes the area as “beautiful in a desolate kind of way”—a place of “sharp mountain peaks and wide, U-shaped valleys.” As someone who has spent a great deal of time in this remote place, he is familiar with the surprising ways in which it has recently changed.

“Every year that I’m back, the ice cliff is different,” said Levy, referring to a research site in Garwood Valley that was brought to the scientists’ attention by a helicopter pilot. “Every year you come back, and basically, the hill [looks] like a big backhoe came in and scooped out the equivalent of a couple of cubic yards of ice and sediment.”

Dr. Joseph Levy / The University of Texas Institute of Geophysics

Meteorology station in front of a meltwater stream coming off the ice cliff and into the Garwood River

This is simply the effect that increased solar radiation has had on Garwood Valley. But what about global warming? For now, Antarctica is shielded from parts of the global climate system by notoriously strong winds and ocean currents that circle the continent, keeping cold air in and warm air out. But fifty years from now, Levy says, global warming will have reached Antarctica, potentially producing more dramatic changes.

And if temperatures rise a couple of degrees by the end of the century, as predicted, then more Antarctic ice will melt and destabilization will occur along the continent’s coasts.

The accelerated melting of the permafrost in Garwood Valley, Levy explained, serves as a “crystal ball” that provides insights into Antarctica’s future.

“The big concern is that the beginning of accelerated melting of the permafrost in the dry valleys is a sign of things to come,” Levy said. “It’s not the end of Antarctica as we know it, but it may be the beginning of the end. It’s a sign that places we think are stable, places where we don’t have an impact, actually, our footprint can be felt there. It’s important to study these places [and] get that baseline data now, because in the coming decades, this is where change is really going to be apparent.”