Why Texas Cattle Ranching Continues to Decline

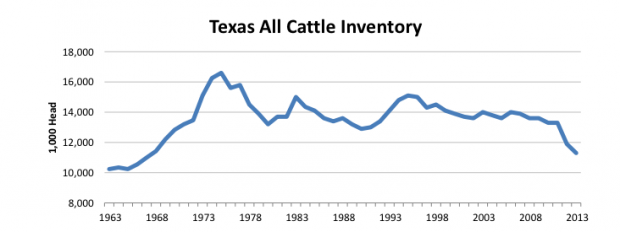

Ranchers and farmers were undeniably the worst-hit when it came to the Texas drought of 2011. After over $7 billion in losses in the agricultural sector that year (with most of those losses in cattle and cotton), some never recovered. Over a million head of cattle were sold out of the state in 2011, and ranching hasn’t made a comeback since:

As of January 1, cattle and calf numbers were at their lowest levels since 1967, with a drop of 11 percent in beef cattle from the year before. Earlier this year, the Cargill Beef Processing Plant in Plainview closed, laying off 2,000 employees. That was about ten percent of the town’s population.

As the drought that began in October 2010 persists in most of the Western half of the state, there’s good reason to worry that another dry year will be devastating for many Texas ranchers.

In the Panhandle, one of the main ranching areas of the state, conditions are “extremely dry,” says Ted McCollum, Professor and Extension Beef Cattle Specialist with the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service.

“Since this drought started in 2011, our rainfall has been in the 10-13 inch range for the last couple of years,” McCollum says. A typical year will have nearly double that, with much of it coming in the summer months. That’s when forage is grown and then used for cattle through the rest of the year.

But without rain, forage for the cattle doesn’t grow, leaving two options: ranchers can buy hay or feed, or sell off part of their herds, both of which cut into the bottom line. “We have some people who have completely sold off their herds,” McCollum says, “because of the drought.”

Current forecasts call for the drought to continue or get worse in the Panhandle, much of which is already in the most severe stages of drought. Even if the region gets normal rainfall this summer, McCollum says conditions are now so bad that range areas “aren’t just going to spring back to full productivity.” It could take two to three years of normal rainfall before ranching areas in the Panhandle are as productive as they once were.

In South Texas, some ranchers are helped by an oil drilling boom.

“The cows seem to be doing quite well around the oil wells,” says Ed Walker, Manager of the Wintergarden Groundwater Conservation District.

Ranchers that sell or lease their land to drilling companies can afford to buy feed to keep their herds going, Walker says, but overall cattle numbers are down in the region. “The guy that’s just out there running cattle on his place, he’s sold out or sold [his herd] way down, because he doesn’t have any grass.”

For the less fortunate, there are drought insurance programs for ranchers available. But cattle losses continue to pile up, and for some older ranchers, rebuilding a herd isn’t an attractive option. “They may be looking at it and going, ‘I don’t know if I want to spend the rest of my life rebuilding a cow herd,'” says McCollum.

The Texas legislature approved funding for new water infrastructure this session, with $2 billion in seed money. If voters approve the water funding, ten percent goes towards rural projects and another 20 percent towards conservation that could be used towards agricultural projects.

But it’s not clear how the water funding would solve challenges brought by drought in places like the Panhandle.

“There is no rebuilding occurring in this part of Texas right now,” McCollum says. “We’re still coping with conditions. And a lot of folks are hoping they don’t have to cull their herds any more than they already have.”