In Texas, Using Fire to Protect and Expand Water Supplies

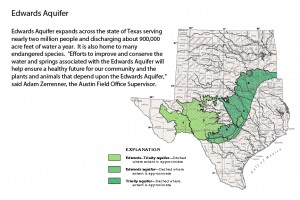

Fire and water may seem at odds with each other, but Austin’s city-owned water utility is using prescribed burning in an effort to help more rainfall make its way underground to the Edwards Aquifer.

Courtesy of Austin Water's Wildland Conservation Division

A fire official with the Wildland Conservation Division starts a blaze with a drip torch at a 2009 prescribed burn on Water Quality Protection Lands in Hays County.

Austin Water’s Wildland Conservation Division is conducting the burns on over 380 acres of Hay County that feed into the Barton Springs Segment of the Edwards Aquifer. The goal of each blaze is to remove brush, cedar, large plants and invasive species that can crowd the land and displace the native grasses. The division oversees prescribed fires on between 2,500 and 5,000 acres of preserved land each year.

“If there’s a woodland environment and it rains, about 30 to 40 percent of that water will be captured in the canopy of those trees,” says Amanda Ross, spokeswoman for the Wildland Conservation Division. “But grasses will allow the water to come down to the ground and run off slowly into nearby creeks or percolate into the soil through the deep root systems of the grasses.”

The fires mimic naturally-occurring wildfires in order to maintain a grassland habitat, Ross says.

The Wildland Conservation Division manages about 26,000 acres of Water Quality Protection Lands – city-owned preserves first established in 1998 to maintain healthy recharge of Austin’s groundwater through urban growth and development.

About 60,000 people rely on the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer as their main or only source for drinking water, says Brian Smith, a scientist with the Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer Conservation District. There are even several hundred wells in Austin. But unlike surface reservoirs, the aquifer can’t fill up in a single heavy rain.

“When we’re in very severe drought conditions and we get a rainy period with a lot of good storm flow in the creeks, it still takes several months for the aquifer to get back to non- drought conditions,” he says. “It’s not something that can just fill up overnight because only a small portion of water flowing in streams actually recharges the aquifer. Even in a heavy flow, there’s a limit to how much water can go into all these openings to fill up the aquifer.”

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services / Warren Grove Range

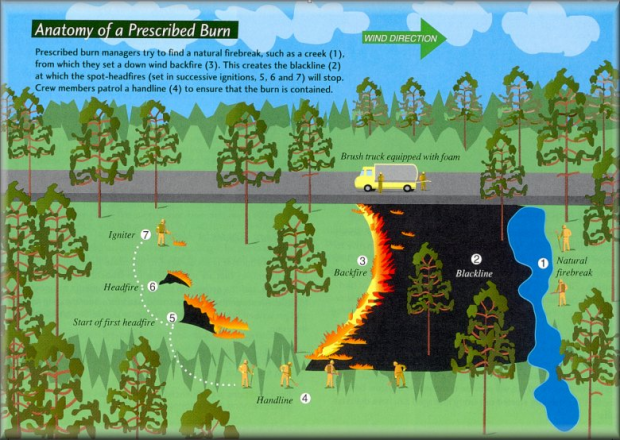

In a prescribed burn, firefighters set a line of fire to burn against the wind then start flames upwind at the place they would like the blaze to stop.

Austin was the first U.S. city to create Water Quality Protection Lands. In 1998, Austinites voted to issue $65 million in city bonds to acquire 15,000 acres of land, most of which was slated for development, and preserve it for the express purpose of protecting groundwater recharge zones to the south and west of the city. Since then, the city has continued to buy out land in the recharge zones to protect water quality. Other cities, including Denver, Colorado, have followed Austin’s example and taken steps to prevent development in groundwater recharge zones, says Ross.

A recent study from Texas A&M found that statewide groundwater levels have fallen substantially over the last 80 years, partly due to concrete ground covering in cities and neighborhoods, which prevents rainwater from reaching the aquifers.

Most of Texas has grappled with strained water supplies for several years. Even though the Barton Springs Edwards Aquifer Conservation District declared no drought conditions for the aquifer last November, maintaining the supply of groundwater remains a serious concern.

“It’s very likely that at the next board meeting on the 24th of July our board of directors will meet to consider all the data and very likely we will be going back into drought status,” says Smith. “Water levels in the aquifer are going down because we’re getting very little rain and we don’t have very much water in the creeks while water continues to flow out of Barton Springs.”

In addition to Austin Water’s Wildland Conservation Division, Monday’s prescribed burn was also managed with the Austin Fire Department, The Texas A&M Forest Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.