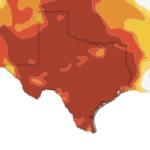

San Antonio’s Lessons for a Nation Parched By Drought

Photo from Nan Palmero via Flikr http://www.flickr.com/photos/nanpalmero

San Antonio is considered a leader in municipal water policy, and with much of the country in drought other cities may start taking notice.

With families picnicking, children playing, and ducks quacking along the river, visitors to San Antonio’s Brackenridge Park on a recent afternoon would be forgiven for forgetting the drought that’s plagued Texas for well over a year.

That is, until they hear the pumps.

Tucked discretely behind the Witte Museum, the water pumps produce a steady hum, churning treated waste water into the river and allowing it to flow with the strength of a waterway in a far wetter place. The water re-use system keeps the San Antonio River rolling, and keeps people visiting the popular River Walk.

That’s right, this park’s beauty is brought, in part, by water that was recently flushed down the toilets of the Alamo City.

“It’s kind of gross, but it’s okay. It doesn’t bother me too much,” Ashley Castillo says as she fishes off the riverbank with her husband and two small daughters.

“I like how the water lilies grow on the water, and then all the little fish have their little homes down,” said Castillo. “Its really pretty. It doesn’t look like it’s recycled water it just looks like their natural habitat.”

Though, in case you were wondering, she doesn’t eat the fish she catches.

“No!” she says with a laugh, “I wouldn’t recommend that!”

‘Water’s Most Resourceful City’

Water re-use is just one reason why San Antonio bills itself as “Water’s Most Resourceful City.”

Since a lawsuit in the 1990s forced San Antonio to conserve water for endangered species in the Edwards Aquifer, the city has become a poster child for conservation. Now, as drought grips parts of the country less accustomed to water shortages, officials here think they may have some lessons for other cities. So many lessons that they’re sometimes hard to keep track of, says Chuck Ahrens, Vice President for Water Resources and Conservation for the San Antonio Water System (SAWS).

“In fact, I made myself a list,” Ahrens tells StateImpact Texas. “I thought, ‘Wow, I don’t even know all of our programs.'”

Photo by Mose Buchele

Charles Ahrens is VP of Water Resources and Conservation for the San Antonio Water System.

That list includes big-money projects like water re-use, brackish water desalination, and underground aquifer storage. But the city’s greatest success is found in simple conservation.

In San Antonio, regardless of the drought conditions, people cannot water their lawns between 10:00 AM and 8:00 PM in order to curb evaporation.

The city has given out over a quarter million “low-flow” toilets to cut back on water use. That’s done more than just save water, it’s also saved money in water treatment.

“And we see that at our waste water treatment plant, a reduced load of waste water that needs to be treated. So there’s benefits beyond the obvious,” says Ahrens.

The city also offers free audits to show home owners where they can save water. And if they can’t afford new pipes, there’s a program called “Plumbers to People” in which the city subsidizes water-saving home improvements.

A History of Growth

As important as the specifics of these programs is the fact that San Antonio has managed them during a time of explosive population growth. In a recent census report, San Antonio was listed among the fastest-growing cities in the country, but its water use hasn’t increased. In fact, the city still uses about the same amount of water it did in the early 90s.

“Other cities have the advantage that they can see that San Antonio has managed water conservation and we are still growing,” says Calvin Finch, Director of Texas A&M University’s new Water Conservation and Technology Center. (It should also be noted that he used to work for the San Antonio Water System.)

Photo by Mose Buchele

Calvin Finch used to work for SAWS. He now heads Texas A&M's Water Technology and Conservation Center.

But exporting that expertise is sometimes easier said than done. A few years ago, Robert Puente, the Director of the city’s Water System, was called out to Atlanta when that normally water-rich city faced a serious drought.

“[We] went out there and gave some talks and made some presentations,” Puente remembers. “They were well received. But [the attendees] did leave scratching their heads. They didn’t necessarily understand or agree with what we were doing here in Texas.”

He sums up SAWS’ business philosophy this way: “To convince customers to buy less of our product.” And he says that seems backwards in parts of the country where drought it uncommon. In San Antonio, for example, the more water you use, the more you pay per gallon. Currently only about half of water utilities nationally use so-called “tiered” rates, according to the American Water Works Association. Some even have the opposite rate structure.

“There’s a number of communities that still reward extra water use,” says Calvin Finch. “Like if you buy in volume, you get a discount. And then there’s even more communities where I think the cost per unit is not much different.”

A San Antonio model for water conservation may be an even harder sell during times of fiscal belt-tightening, when cities might be less willing to create dedicated funding for conservation, as they have in San Antonio.

And even as the city holds its conservation program up as an example for others, officials there admit that San Antonio is not immune to the pressures of growth.

“Even if you do fulfill the full potential of water conservation, a lot of cities still will need new water resources,” says the Water Conservation and Technology Center’s Finch.

San Antonio is one of those cities.

Challenges Ahead

“Despite all of our water conservation measures, and the business community loves to hear this, that’s not the total water supply that we’re looking into,” says SAWS’ Puente. He says the city is investing big money into water supply projects “that we previously had been able to push off.”

Those include more re-use, like the system at Brackenridge Park. They also include a multi-million dollar brackish water desalination project, and an ambitious underground aquifer storage system. The expense of those projects has forced SAWS to raise rates, and everyone interviewed for this article agrees further rate hikes are inevitable.

“The cost of water is definitely going to go up,” says Ahrens of SAWS. “There’s only so much out there, each project is going to probably be more expensive than the last.”

But, he says, more expensive water is not completely undesirable, especially in San Antonio where water has traditionally been very inexpensive.

“When I was growing up [in San Antonio] there were no watering restrictions, and I never remember my dad saying ‘Hey, shut the sprinkler off!’ But you did hear ‘Hey, close the door! The air conditioning is on!'” says Ahrens.

“And I think over time, with the pricing of water, that [concern over waste] will be a reality as water gets more expensive,” he says.

There will be regional shifts in water use as well, says the Water Conservation and Technology Center’s Finch.

“Not every farming area is going to able to afford the high cost of water in the future,” Finch says. “We’ve gotta identify those crops and cultural practices that allow agriculture to prosper. And it may include some shifting of agricultural production from one area to another area.”

Those are the types of projects that will ensure that the San Antonio River keeps flowing well into the future for people like Ashley Castillo and her husband Miguel back in Brackenridge Park, who ended up pulling in a fish on their family outing, much to the delight of their daughter Addie.

“It’s a little perch, that’s all,” says Miguel as his daughter dances around the shining catch. It may be “just a perch” but it’s also something that wouldn’t be possible in this time of drought if not for years of planning and investment.