Life By the Drop: Dry, the Beloved Country

Photo by Mose Buchele for StateImpact Texas

A cow that perished on a ranch outside of Marfa was dried "like jerky" by the drought.

Jake Silverstein of Texas Monthly contributed to this article.

It’s a disaster unlike any other. Floods, hurricanes and earthquakes enter swiftly and destroy efficiently. But a drought doesn’t herald it’s arrival. And people usually don’t pay attention to drought until the damage is already done.

For most Texans, especially those living in big cities, a drought is usually little more than an irritation—a brown lawn or a high water bill.

But for Texans living in the country, it’s a little different. For them, a drought is impossible to ignore.It can mean the end of a family tradition or a way of life.

Yet it requires a truly extreme drought, like the one we suffered last year, before the average city-dweller sits up and takes notice.

What happened during the drought was unprecedented—an average of just 14.8 inches of rain fell across the entire state. It was the driest year in recorded Texas history.

Photo by Filipa Rodrigues/StateImpact Texas

Pati Jacobs on her cattle ranch outside of Bastrop, Texas

When Texas Monthly, KUT and StateImpact Texas sat down to plan our special coverage of the drought, we knew we had to begin with the folks who are at the front lines. The people who watched clouds form on the horizons. People like Bastrop rancher Patti Jacobs.

“We lost effectively between 600 thousand and a million head of cattle in this state,” Jacobs says. “And what most people don’t realize is, this wasn’t a one year drought. It’s been going on for 3 or 4 years.”

Agriculture losses eventually topped $7 and a half billion. Ranchers sold off whole herds; some gave sound horses away to keep them from starving. Hay salesmen like Valentine Hernandez traveled half the country each week to bring food back to desperate cattlemen.

“Oh yeah its hell,” explains Hernandez. “Cause we gotta go so far to get hay to sell to people around here. Hay comes from Florida, California Tennessee. Everywhere. Ain’t no hay in Texas cause we ain’t had no rain.”

Hay prices skyrocketed. Those with animals were stretched to the limit. Stephanie Reed owns a small ranch in Dale, Texas. She started last year with 22 horses. By October she was down to 6.

“I have a couple of horses that are dear to my heart,” Reed says. “Those horses, I would starve myself before I had to get rid of them. Sell my truck, my trailer, I’d get whatever I could to pay for feed for them. There are days we don’t eat dinner. There’s so many thing that need improving around here things that were plans and dreams that are not gonna happen. Not in Texas, not here.”

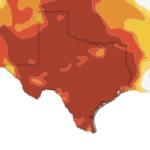

By the fall, the U.S. Drought Monitor Map showed eighty-eight percent of the state was in “exceptional drought.” In many towns, what wasn’t turned to dust by the heat was burned to ash by wildfires. In Central Texas, Bastrop was hit by the 6th worst fire in U-S history. 13-year-old Connor Tausch saw firsthand how fast life could change.

Photo by Terrence Henry

The Tausch family (clockwise from upper left): Chuck, Kasey, Connor and Jesse

“I was at a friend’s house and someone said there was a fire on 21 and so we were getting our stuff,” Tausch recalls. “And I look out the front door and it was just pitch black going over the front of our house. And we took off to go help our neighbor friend to get out of her house because the fire was right there and here I am uh, the fire was right there in his back yard, and oh, I started crying and stuff and usually I don’t do that. It kind of freaked me out.”

And still the drought wore on. Towns like Spicewood Beach, Groesbeck, Robert Lee and Llano grabbed headlines. As one by one, they began to run out of water.

But by spring of this year, plentiful rains had pulled most of the state out of extreme drought.

Neal Newsom farms wine grapes in the High Plains of West Texas.

“Well the dryland farms in our area are pretty much abandoned, they’ve done all they can until they get more rain,” Newsom says. “You can scratch it a few times and rough it up where it doesn’t blow. But there’s nothing to do until it rains again and we’ve been waiting on that for a year now.”

For some, like Doris Steubing, there will be no coming back from the drought. She raises cattle in Maxwell. “A lot of people they just didn’t want to fight the drought, they just sold out,” Steubing says. “They didn’t have the means to afford the feed for their cattle.”

Photo by Terrence Henry/StateImpact Texas

John Jacobs looks out over the dry EV Spence reservoir in West Texas.

It’s impossible to predict when the next drought will come; or even how bad this one might still turn out to be. State climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon sees it as a kind of warning.

“This drought at least has woken people up to the concept that it’s possible to be worse than the 50’s,” Nielsen-Gammon says. “We certainly had the worst one-year drought on record. The rain at least means part of the state it’s not gonna last long enough rival the 1950’s. But in other parts of the state it still can. And there’s no guarantee that the summer will be wet or next year will be a wet year.”

There’s a very simple idea that this all adds up to: Life in Texas would be easier if our climate was wetter, but it wouldn’t be life in Texas. Drought is part of our heritage. This was probably more widely understood when the state was more rural. In 1950 the population split between cities and rural areas was around sixty to forty; today it’s almost ninety to ten.

But though the residents of our growing, thirsty cities may be more insulated from the effects of drought than their counterparts in the country, they are the very ones whose policies, routines, and expectations will determine whether our supply of water will be enough to go around.