How Texas Voted On Prop 6, and What it Could Mean for the Water Plan

How Texas counties voted on Prop 6. Counties in Blue passed the measure; Counties in Red voted against it. Map by Matt Wilson/StateImpact.

There wasn’t much nail-biting on either side of the Proposition 6 debate as people watched the votes come in on Tuesday. The measure, which will move $2 billion dollars from the state’s Rainy Day Fund to start a fund for water projects, won approval from over 73 percent of the state.

But as poll watchers began digging into the turnout, competing versions of what those numbers mean for the future of water in Texas began to take shape.

Speaker of the House Joe Straus, R-San Antonio, led the Water Texas PAC, which spent nearly two million dollars to promote the measure, pointed to the broad base of support to call the victory a triumph for bi-partisanship and coalition building.

“Small businesses, manufacturing, the energy industry, farmers and ranchers all came together very strongly,” said Straus at his PAC’s election night party.

Opponents of the measure say the way people voted points to a looming confrontation between water-rich rural areas and thirsty urban consumers.

“Let it not go unnoticed that home of the Speaker’s efforts to move groundwater — Bastrop and Lee counties, and our neighbors in Austin County — (not to mention nearby Fayette, and Lavaca counties) Nixed Prop 6!” Linda Curtis of the Libertarian group Independent Texans, which opposed Prop 6, wrote today.

Several of the 18 counties that voted against Prop 6 are in wetter parts of the state. “Along the Louisiana-Texas border, they get about 45 to 50 inches of rain per year,” says Victor Murphy, Climate Program Manager with the National Weather Service Southern Region. That’s significantly more rain than Seattle gets on average.

Head out to Far West Texas, and you’ll find average rainfall of ten to fifteen inches, Murphy says. Those areas of the state tended to pass Prop 6 by a larger margin.

The potential for the new system of funding water projects in Texas to create conflict was already on display on election night.

Luke Metzger with the group Environment Texas, supported Prop 6. But at the Water for Texas party he was already speaking out against some projects in the water plan.

“We need to make sure that as they’re investing in our water infrastructure they’re avoiding projects that are really harmful to our rivers and our forests like the Marvin Nichols Reservoir,” said Metzger. “That would flood 25,000 acres of increasingly rare forest area in Northeast Texas.” Residents in the one of the counties where the proposed reservoir would lie, Red River County, voted against Prop 6 with 57 percent of the vote.

There’s a large dividing line of rainfall in the state, and one big question going forward is where the new water projects will be, and what form they will take. East of the I-35 corridor, Murphy points out, the reservoirs are doing pretty well. “They’re all 80 percent full or greater,” he says. But in West Texas, lakes and reservoirs in that area of the state are only a between 24 and 34 percent full, according to data from the Texas Water Development Board.

The history is instructive. After building massive reservoirs in the late 1960s and early 1970s in West Texas, the water supply in that region expanded dramatically. But Murphy says that those healthy reservoirs were also the result of good luck: the decades after they were built were a historically wetter- and cooler-than normal period in the state. “Times were good, the reservoirs stayed relatively full and no one even thought about it,” Murphy says.

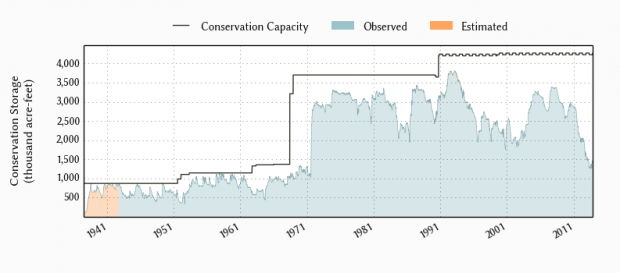

Graphic by TWDB

After several reservoirs were built in the 70s, water supply in West Texas increased dramatically. But it also coincided with a wetter-than-normal period in the state. Since rainfall returned to normal, and then extreme drought struck, the reservoirs have dropped precipitously.

Since then, rainfall has returned to normal. Then during the last few years, drought has taken over, and those reservoirs have dropped dramatically. Some, like E.V. Spence and O.H. Ivie, now sit nearly empty, rendering them useless. The reservoirs in that region, despite having increased their capacity four times over since the drought of record, are now holding near the same amount of water that they did during that very dry time.

“Are these things sustainable?” Murphy asks. And if reservoirs aren’t working, what will? If the rain in Texas falls in the east, why not just build new reservoirs there, then pump the water where it’s needed?

“By and large, the Western part of the state is higher in elevation than the eastern part of the state, and it costs a lot of money to build huge pipelines” to move the water, Murphy of the National Weather Service says. Moving water from rain-blessed parts of the state also opens up a host of other issues: regulatory issues, environmental impacts, and property rights.

How to provide water to West Texas will be one of the big challenges for the new water fund, Murphy says. “I think we’re finding out from all these reservoirs drying up that the answer isn’t building new ones in West Texas.”

Supporters of Prop 6 downplayed the notion that much of the new money will go to reservoir building, whether in the east or the west. “Unfortunately, Texas is becoming way way too dependent on mother nature,” State Senator Troy Fraser, R-Horseshoe Bay said at the election night party. “What I’m hoping we’ll do with the Water Development Board is we’re going to think outside the box.” That means projects like groundwater desalination (Texas sits on an ocean of salty water that could potentially be tapped), wastewater reuse, and storing water underground in aquifers, where it would be spared from losses to evaporation.

“We’re not going to ignore reservoirs,” Fraser said. “We’re going to continue to build them. But we’ve got to do things that are ‘Mother Nature-Proof’.”