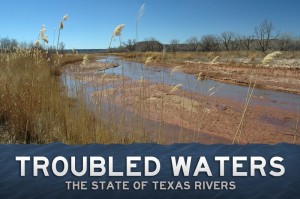

Along the Canadian River, Concerns About Drought and Threatened Fish

AMARILLO — By an interstate overpass along the languid Canadian River near Amarillo, off-road vehicles zooming by are a common sight.

AMARILLO — By an interstate overpass along the languid Canadian River near Amarillo, off-road vehicles zooming by are a common sight.

“They get in the river and run up and down it,” said Gene Wilde, a professor of biology at Texas Tech University. It’s legal, he said, but “they’re not supposed to get in the water. Technically, if there was a federal marshal out here, that is harassing the fish.”

Wilde has reason to care: The Arkansas River shiner — not a beer but a small, silvery minnow — likes to spawn in this river, with its sandy shores. The fish, which is no longer found in Arkansas, has a prime spot on the federal government’s list of threatened species. Drought diminished the river — and the fish — so badly two years ago that Wilde and others collected shiners to take to a hatchery in Oklahoma.

But the Canadian’s challenges go well beyond off-roaders bumping through delicate habitat. The river itself is “pretty puny,” said Kent Satterwhite, general manager of the Canadian River Municipal Water Authority, which supplies water for Panhandle cities and industries. Despite its name, the authority now gets its water from the Ogallala Aquifer, and two years ago it spent tens of millions of dollars to buy more Ogallala rights from the oil billionaire T. Boone Pickens.

It is a sorry state for a storied river, whose banks were once roamed by Billy the Kid and whose name may derive from confused explorers who believed it flowed to Canada. The Canadian rises in the mountains of New Mexico, then meanders northeast through the Texas Panhandle, where it passes landmarks like Pickens’ ranch and the caprock before getting to Oklahoma and eventually flowing into the Arkansas River. Some water in the river filters up from the Ogallala Aquifer, according to Satterwhite. Other Ogallala water flows into the Canadian from manmade lakes on Pickens’ ranch, said Monty Humble, an Austin energy executive who used to work for Pickens.

A half-century ago, the three Canadian River states signed a compact divvying up the river water. New Mexico gets the first rights, to store 200,000 acre-feet of water (roughly equivalent to twice Austin’s annual use). Beyond that, Texas can capture up to 500,000 acre-feet. But these days, with the drought, there is little to capture — which is why Lake Meredith, which was built to hold the Canadian’s flows, is empty. Oklahoma gets any leftovers.

Essentially, the compact was a strategy for managing floodwaters, said James Herring, an Amarillo businessman appointed in 2011 by Gov. Rick Perry as Texas’ compact commissioner. That explains why the compact has been relatively amicable, unlike those governing the Red River or the Rio Grande. Oklahoma has occasionally raised concerns about the Palo Duro reservoir, near the top of the Texas Panhandle; the state has complained in the past that it stores Canadian River water but does not use it to supply cities, as specified in the compact. Texas and Oklahoma had similar complaints about a New Mexico reservoir 20 years ago. But currently, there is no compact-related litigation.

“There’s nothing to fight about when there’s not any water moving down the Canadian,” Herring said.

Compounding the low rainfall is the spread of water-hogging salt cedar, a plague throughout Texas. The Canadian River Municipal Water Authority has spent around $2.5 million to combat it, according to Satterwhite. The latest strategy involves a salt cedar-munching beetle.

“Just this year, it started to really take off,” Satterwhite said. “I’ve been very disappointed with [the beetle] in the past.”

Beating back salt cedar would also help the Arkansas River shiner, which suffered badly when the Canadian River was reduced to puddles a few years ago. During that record-breaking summer of heat and drought, Wilde scooped up shiners and another flailing fish, the peppered chub, to take to an Oklahoma hatchery. The surviving shiners were in poor health: “They had been trapped in pools and warm water for a long time, and a lot of them showed evidence of external parasites,” Wilde said. Because the shiners were so weakened, the hatchery’s spawning efforts fell short.

The shiner is still trying to recover from 2011. But this year, a few decent rains have lifted Wilde’s hopes. This month, he will drive up toward Amarillo, to pull nets through the water and count the number of small new shiners. “We’re hopeful that we’re going to have a good spawn,” he said.

The eventual goal is to allow the shiner to recover enough to get it off the threatened species list, where it has been since 1998. The federal Fish and Wildlife Service is in the process of organizing a team of scientists to discuss the possibility, though they haven’t met yet, according to Wilde.

“There’s ways of managing this,” he said, “but it’s just going to have to take a little bit of thought.”