The Future of Texas State Parks? It’s All About the Money

For state parks in Texas, the struggle has always been money. In the early 1900s, Texas landowners tried to donate large tracts of property to create state parks. But they were turned down by state lawmakers — they didn’t want to fund the maintenance cost. So when the land was accepted, it was without the promise of upkeep. Now, as the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department winds down its 50th year in operation, it seems like very little has changed.

“I think, in a way, the parks exemplify the worst that we’ve got in budgeting, as far as the Senate and House are concerned,” state Rep. Lyle Larson, R-San Antonio, said at a panel on parks during the Texas Tribune Festival earlier this year.

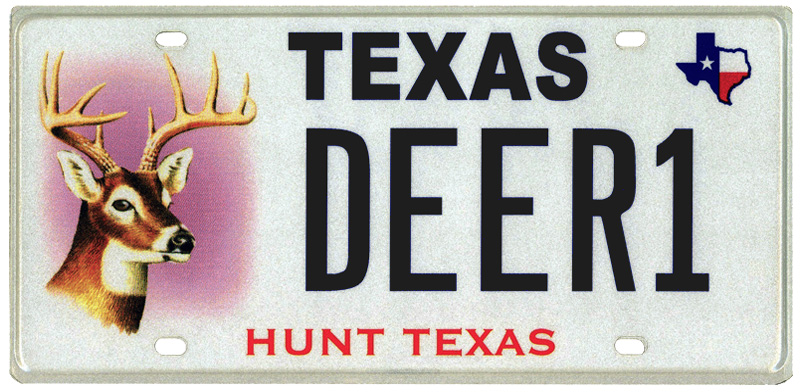

And here’s why he thinks that: Texas Parks and Wildlife is the only state agency with a dedicated sales tax. Under state law, a portion of the sales tax on sporting goods is meant to go for parks. But lawmakers consistently divert some of that money to balance the state budget.

“If you’re raising $260 million, and you’re using 25 percent of that for its intended purpose, and then you’re back-loading to certify the budget the balance of it — Well, then you’re leaving your parks out.”

The situation was even worse for parks a few years back when the department’s budget was slashed along with those of most other state agencies.

This year, lawmakers restored much of that money, but came nowhere close to providing enough for park upgrades, to say nothing of acquiring more parkland.

“So what we have done is looked to the private sector,” said Carter Smith, executive director of Texas Parks and Wildlife. “And we’ve had just an artesian well of support in that regard.”

Courtesy of Texas Tribune (Photo by Spencer Selvidge)

Mose Buchele (far left) moderates panel featuring (left to right) George Bristol, Carter Smith, Port Isabel Mayor Joe Vega, and state Rep. Lyle Larson

Smith spoke at the same panel. He talked about land and money donated form private groups and individuals for parks.

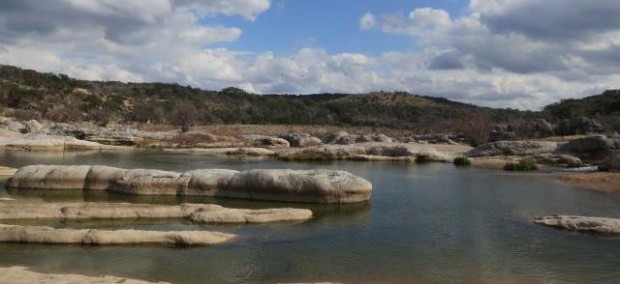

“We’ve acquired big tracts of land on the Devils River, the Kronkosky State Natural Area near Representative Larson’s district, which he knows very well. Literally just 30 minutes from downtown San Antonio, almost 4 thousand acres of spectacular Hill Country that was bequeathed to us.”

But here’s where the age-old problem returns: it’s one thing to have the land, and another thing to have the means to install and maintain trails, campsites and other facilities. That’s why so much of the land donated to parks in recent years has sat unsused, says George Bristol with the State Parks Advisory Committee.

“If we get these lands and then they just sit there, after a while generous people are going to start to say, ‘Maybe we better find someplace else to park our donations,’” says Bristol.

It will take a greater commitment from lawmakers to fund parks to stop that from happening, he says. And that will likely only come from political pressure.

Rep. Larson sees an opportunity for just that in the next year’s statewide elections.

“Talk to the folks that are running for office, and talk to them about parks,” Larson said. “Are they committed to stopping the diversion of the sporting good tax?”

Of course, with hot-button issues like abortion, education funding, and gun control already making headlines, parks advocates will probably have a hard time getting their voices heard over the din.