Where We Stand: The Texas Drought

Texas is now in its third year of drought—but is the end in sight, or are conditions getting worse?

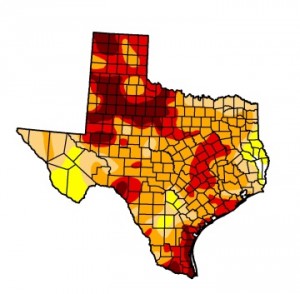

Far more of the state is in extreme or exceptional drought now than in July 2012. The Panhandle and the Southeast Texas coast, which are important regions for ranching and agriculture, have been especially hard-hit. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, over 90 percent of Texas is in drought, and about 35 percent is in extreme drought.

To prevent water shortages, 665 public water systems have implemented mandatory water restrictions, according to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. In many rural areas, farm and pastureland soils are dry, and grasshoppers, which eat crops, have become a problem. (The insects’ populations increase during droughts because the fungus that naturally limits their growth does not grow without moisture—although an extreme drought can prevent grasshopper eggs from hatching.)

The drought is not just a Texas problem. Most of the American West is in drought. The worst-affected regions are the state of New Mexico, and the entire Ogallala Aquifer region, stretching from the Texas Panhandle to Nebraska.

The Ogallala Aquifer, which has a storage capacity approximately equal to that of Lake Huron, provides nearly all the residential, industrial, and agricultural water in the surrounding High Plains region. Drought in the High Plains has led farmers there to pump additional water from the aquifer, accelerating its decline. Depletion of the Ogallala has been especially severe in Texas. In only a year, wells have dropped an average of 1.87 feet in a 16-county area from Amarillo to south of Lubbock.

While the West struggles, the eastern half of the United States has almost entirely pulled out of last summer’s drought, according to U.S. Drought Monitor data. A series of storms, including Tropical Storm Andrea, brought significant rainfall to the entire Atlantic seaboard, according to the National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center.

By 2100, U.S. temperatures are predicted to increase by 3 to 5 degrees, according to the 2013 National Climate Assessment. If global greenhouse gas emissions continue rising, national temperatures may increase by as much as 5 to 10 degrees. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, climate change is expected to put greater strain on water resources in the Southwest.