Texas’ Biggest Cash Crop, Cotton, Makes Gradual Rebound

Flickr/Creative Commons

The white fruit of the cotton is called the boll. Texas has led the nation in cotton production for over a century.

Texas is cattle country, an image known the world over. What’s perhaps not so well known is the primacy of the other big C: Cotton. In fact, Texas has led the country in cotton production for over a century.

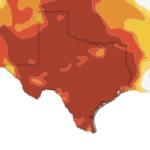

The fate of the state’s cattle industry as it recovers from last year’s drought is well documented. But what of an industry that rivals ranching in economic dominance? How has cotton faired?

To find out we talked to State Extension Cotton Specialist, Dr. Gaylon Morgan. His overall take is positive, especially when compared to last year.

“35 percent of the [state’s] crop is good to excellent right now, 39 percent is fair, and then 26 precent is poor to very poor,” Morgan says. This time last year, he contrasts, “nearly 60 percent of the crop was poor to very poor.”

Even though farmers “were quite cautious” this year because of last year’s foreboding conditions, the wet winter allowed growing conditions to improve somewhat, says Morgan. But just how good improvement has been depends on the region.

For farmers in the Panhandle and Rolling Plains to the south, the weather really has not been wet enough to promote growth. Although there was some moisture, the ground was not saturated enough at the time of planting to “fill up the soil profile, basically how deep those roots go in the soil.” There was enough rain “to get the crop up” but not enough to promote strong growth. At this point, it’s a wait-and-see game if the rain will come to drive growth.

In the area of Central Texas from roughly Austin over to Houston, on the other hand, “the cotton looks great cause they did get a decent amount of moisture, and they’ve had some during the season.” Morgan adds that South Texas has also done quite well with the exception of the Corpus Christi area that “missed a couple of critical rains in the winter and spring.” As a result, “their cotton yields are gonna be horrible this year.”

Texas’s cotton yields may not be robust as of late, but it’s precisely because of the state’s volatile climate that it is suitable for growing cotton. Cotton can yield fruit – the downy, white boll – even when conditions are pretty dry. Dr. Morgan explains that this has much to do with the fact that growers treat it as an annual even though it is actually a perennial. Meaning: instead of letting it grow over the years as it is programmed to do, like a tree or bush, it is taken out of the ground and replanted each year.

The reasons for this are several, Morgan says. Too big of a plant would preclude mechanical harvesting, getting rid of the plant every year also rids it of pests, and it is not tolerant enough of the cold to survive harsh winters.

The side benefit of its perennial nature is greater adaptability to ambient circumstances. Unlike annuals that must focus a lot of energy on reproduction, a perennial’s first order of business upon planting is “to put a deep root system down because it thinks it’s gonna be there…one year, two, three years from now,” says Morgan. Deeper roots means access to more groundwater.

In addition, it adapts its yield of fruit to how much water is available. A lot of water is not a bad thing; it simply means more fruit. “If things get dry or stressful” though, Dr. Morgan explains, “it will actually abort fruit, and then if it gets rain it will put fruit back on again.”

This flexibility is precisely why it is well-suited to Texas’s volatile climate. But it is possible to be just too dry to bear any fruit. That’s what happened last year.

Department of Soil and Crop Sciences website / Texas A&M University

Dr. Gaylon Morgan is the State Extension Cotton Specialist. He is also an associate professor in the Department of Soil and Crop Sciences at Texas A&M.

And last year’s conditions may seem like natural impetus for farmers to adopt a more conservative stance, but this is more easily said than done. Much of this has to do with the upfront cost of efficient irrigation. Drip irrigation systems, the most efficient method for drylands, are expensive. “It’s literally in the thousands of dollars an acre to put it in.” Still, about 25 percent of cotton cropland in the Pandhandle uses it.

This doesn’t mean that farmers aren’t seeking alternative ways to save water. Morgan notes that many West Texas farmers are saving water by changing their tillage practices. Tillage basically means how a farmer decides to move up and down a field for the various processes needed to produce a crop, from soil preparation to planting to applying fertilizer, etc.

Each time a farmer makes a trip through a field, the machinery can turn up the soil, releasing stored up moisture to evaporation. The machinery can also strip away valuable plant residue, or mulch, which acts as a natural moisture retainer.

“Right now,” Morgan says, “we’re probably a quarter of the tillage events that they were doing 20 years ago.” Part of this involves investment in new, more efficient equipment that minimizes soil disruption, but another part is simply reducing how often and how many trips through a field are made.

Morgan’s overall outlook for the industry seems positive due to the advancements being made in practices and technology. For instance, he explains that more economical center-pivot irrigation structures are being designed to minimize water loss to evaporation. Other innovations will be “site specific irrigation based on soil type or yield potential” or a combination of these factors.

But innovation is only as good as a conservation of resources allows. In the meantime, Texas remains a cotton king.