How Stressed-Out Plants Are Better Prepared for Drought

Photo courtesy of Center for Plant Science Innovation/UNL

Professor Michael Fromm says plants remember stress, and that can help them weather droughts.

Do you remember the last time you were stressed out? You’re not alone. According to a new study, plants are feeling it, too. The report says that plants have a sort of “stress memory,” and it could help them survive drought.

Researchers at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln have recently confirmed what gardeners have long claimed: after surviving the stress of a drought, plants are better able to withstand future droughts—in the short-term, at least.

The team worked with Arabidopsis, a member of the mustard family, to compare stressed plants (plants that had been previously dehydrated, like in a drought) to non-stressed plants (plants that had never been dehydrated) in a simulated drought situation. The pre-stressed mustard plants consistently rebounded far more quickly than the non-stressed mustard plants.

Fromm and his team repeated this study with two other species, and the results were the same: plants are smart. They remember they’ve been in this situation before, says Michael Fromm, professor at the Center for Plant Science Innovation at Nebraska and lead researcher on the study. “We believe that what we’re studying is most important during the drought. It turns out that plants experience kind of a day-night cycle of drought stress,” he says. During the day, Fromm says, plants are losing more water than they can take out from the ground; but at night when it cools off a little and they’re not busy photosynthesizing, they’re no longer losing water and they can replenish themselves. “It’s really the plant remembering day-to-day, gee, it was nasty yesterday and I bet it’s going to be that way today and I’m going to be ready for it,” he says.

It’s worth noting that this plant memory seems transient. After five days of watering, the mustard plant “forgot” the previous stress memory . Other plants, however, might remember for longer or for less.

And the results of this study aren’t entirely unexpected. “This phenomenon of drought hardening is in the common literature but not really in the academic literature,” says Fromm. The understanding of the molecular mechanisms that make this memory work is the most revelatory aspect of Fromm’s research.

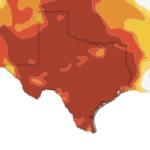

So what does this mean for Texas farmers and gardeners? Mustard plants aren’t exactly a Texas cash crop, after all. But mustard plants are considered great models for general plant research. Still, do all plants have this transcriptional memory? Are some plants smarter than others? Should farmers start choosing which crops to plant with degrees of plant-smartness in mind? Those are some of the questions the team and others like them will be looking at. And Fromm and his fellow researchers are already playing around with the genetic-modification of plants in order to enhance their “memory.”

Lily Primeaux is an intern with StateImpact Texas.