With Rain Falling on Texas Cities, Drought Rages on in the Rural West

Photo by Mose Buchele for StateImpact Texas

A cow that perished on a ranch outside of Marfa was dried "like jerky" by the drought.

Driving a pickup through a ranch outside of Marfa, Texas last week, grad students Justin Hoffman and John Edwards came across a sight sadly common for their region in far West Texas. A cow that had perished in the field.

What was strange about the grisly discovery was the condition of the body. After months in the elements, the animal still looked very nearly intact. The arid weather had dried its skin and organs “like jerky,” says Edwards. He gave its side a knock with his fist, the hollow drum-like thud illustrating his point.

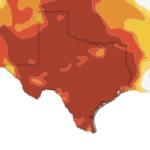

For many Texans who came close to forgetting what rain looked like, this past winter was a welcome surprise. Unusually-wet weather helped Central and East Texas crawl their way out of last years historic drought. But the same can’t be said for the Trans-Pecos region, the far western point of the state, where the drought persists unabated.

Photo by Mose Buchele for StateImpact Texas

Justin Hoffman (left) and John Edwards (right) study resource management at Sul Ross University in Alpine.

Unfortunately, that region is also one of the least populated parts of the state, causing some to worry that its plight could be forgotten if wet weather continues in Texas’ population centers.

“Last year, the whole state was in drought at one time or another and most of the state was in exceptional drought, so we can call it ‘the Texas drought’ and say it’s bad everywhere. That’s the easy five-second statement. But now things are complicated,” John Nielson Gammon, the State Climatologist tells StateImpact Texas.

Now Nielson-Gammon says there’s no more “Texas Drought.” There are different regions in different levels of recovery. And some are not recovering at all.

Dr. Louis Harveson directs the Borderlands Research Institute in Alpine. He says the drought has become so bad in the western point of the state that birds have skipped it over in their annual migrations. Bears are encroaching in thickly settled areas. In one high profile incident last February, a mountain lion even attacked a young boy on a well-trafficked trail in Big Bend National Park. The boy survived, but Harveson, who is an expert in mountain lion behavior, says he expects there will be more conflicts with wildlife if the drought persists.

Photo by Mose Buchele for StateImpact Texas

He knows them, Horatio. Dr. Louis Harveson is an expert in Mountain Lion behavior. He says wildlife has been deeply impacted by the drought in West Texas.

“Even if you’re just walking out there not even looking, it’s like you’re walking on glass. I mean the grass is so dried out and desiccated that you know something’s wrong, How these animals are finding anything to eat is beyond me” he says.

The area will also see more economic hardship and anxiety over its water supply if the drought continues. That’s something that could be exacerbated if political power centers like Austin, Houston and Dallas, stop paying attention.

“Texas is a crisis management state. We lurch from crisis to crisis, the legislature reacts to whatever the crisis du jour is,” State Rep Pete Gallego [D-Alpione] tells StateImpact Texas. “So if there is a perception that the drought isn’t an issue anymore, then the legislature will move on to other issues. Which is unfortunate for us, because we’re not out of the drought.”

If the weather doesn’t improve, it will pose fresh challenges to a population that’s already dealt with its fare share of them.

“This may last longer than we think it’s going to,” Albert Miller, a lifelong rancher and County Commissioner in Jeff Davis County says. Like many ranchers, Miller was forced to cull his herd dramatically last year because of the lack of rain. If this summer brings more dry weather, he says he doesn’t know how ranching will survive.

“If the state could do one thing it would be to fund more studies of where there is groundwater, how much is there and what’s our lifetime on this, particularly out here,” he says.

Like many others, he also wonders whether larger, thirsty cities will try to take the decreasing amount of water that remain n the Trans-Pecos for their own use.

“El Paso is the 800-pound gorilla in the room,” he says with a laugh. In fact, he says, large tracts of land outside of his hometown of Valentine have already been purchased by El Paso for the water that exists underneath.

Photo by Mose Buchele for StateImpact Texas

Albert Miller is a lifelong rancher and County Commissioner in Jeff Davis County. He says no one knows exactly how much water is available for the small rural communities of West Texas.

“We don’t mind sharing, the challenge is that we want to make sure that we’re not giving our lifeblood away,” says Representative Gallego.

“We’ve got this growing business of water speculators that out there who are looking for pockets of water that they might be able to tap into, that they might be able to sell in bigger cities,” he says.

Gallego also worries that the State Water Plan, which received a lot of attention last year when the whole of Texas was in drought, may fall by the wayside if Texas’ populations centers become greener, wetter and more complacent.

Photo by Mose Buchele for StateImpact Texas

Pete Gallego has served as a State Representative out of Alpine, Texas for about 20 years.

“The legislature has chosen not to fully fund the water plan,” he said.

While some wait to see how policymakers will respond, others wait for rain.

Back on the ranch in Marfa, the grad students Edwards and Hoffman watch clouds forming over a distant mountain range. Hoffman wonders if anyone else is paying attention.

“The way I think of it is, this part of Texas is almost like a whole other state, there’s so many differences. And with all your population elsewhere a lot of people forget this part of the state,” he says.

That night, at least, it did rain, bringing a little more relief to a region in dire need of it.