A warning sign in front of the Keystone Dam in Sand Springs.

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

A warning sign in front of the Keystone Dam in Sand Springs.

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

This story was produced in collaboration with Oklahoma Public Media Exchange’s Graycen Wheeler.

Chuck Graham’s family had five hours to pack up their lives before flood waters filled their Sand Springs home with six feet of water.

Left behind were musical instruments, hunting and fishing gear, Graham’s military equipment, memorabilia from grandparents and years worth of memories. Anything that may have been salvageable was pilfered by looters roaming the destruction.

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

At the Graham’s abandoned Sand Springs home, a waterline marks the peak of the flood waters’ rise. Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

“We lost everything,” Graham said.

While navigating the turbulent waters of flood insurance and restoration companies, their community stepped in to help with the recovery.

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

The Grahams’ Christmas tree stands in their living room. Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

Sitting at his dining room table, Graham surveyed the house the family had been forced to start over in. He gestured to a twinkling Christmas tree in the living room, courtesy of the local community center.

“The guy who runs it, I actually graduated high school with. And he was like, ‘Hey man, I know your family’s lost everything. So I’ve got a Christmas tree for your family.’ And he gave me a Christmas tree,” Graham said. “We weren’t even thinking about a Christmas tree, trying to just get a roof over my family, you know. But we had a Christmas tree. It was pretty neat.”

Graham said between a lack of law enforcement response to looting and a complicated state buyout program that takes years to process, he saw little support from elected officials during the flood recovery. Since the house was abandoned, people have stolen the wiring out of it, their entire carport and looted everything from the attic.

Though Sand Springs residents like Graham experienced catastrophe during the 2019 flood, just eight miles away in Tulsa, it was a completely different story.

1984: A watershed moment for Tulsa

Today, Tulsa is one of the nation’s most flood-ready communities. The city earned a Class 1 rating from FEMA in 2021 — the second city in the country to achieve that accolade.

But Tulsa’s flood readiness looked very different in 1984, when the Memorial Day Flood left 14 people dead, hundreds injured and others temporarily displaced or homeless. It also caused hundreds of millions of dollars in damage.

Gary McCormick, a senior engineer for the City of Tulsa’s stormwater planning, said by the floods of the mid-1980s, much of the city’s infrastructure was still a relic from the oil boom of the early twentieth century.

“There was little to no thought on stormwater issues at that time,” McCormick said. “So we’ve got all these neighborhoods that were built during this timeframe with all these undersized, inadequate storm sewer systems.”

After the 1984 flood, city planners worked with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to address Tulsa’s flooding problems on a grand scale, developing a comprehensive drainage plan to manage water all the way from “rooftop to river.”

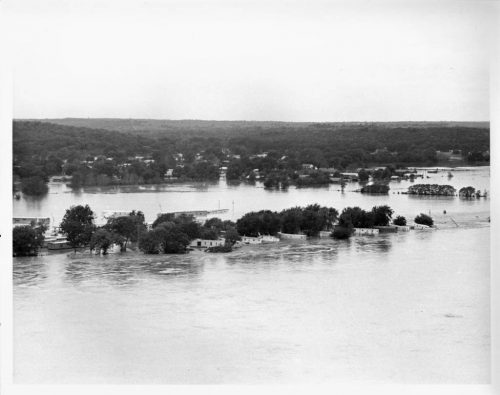

Austin Hellwig Collection / Tulsa City-County Library

Two years after the Memorial Day flood, neighborhoods and mobile home parks in Tulsa flooded from the Arkansas River in October 1986.

The city also developed its own regulatory floodplain maps that are even more conservative than FEMA’s. These maps show where floodplains would lie if they were entirely urbanized, with no pastures or fields to soak up water. FEMA’s floodplains are designed for the way our cities look today; Tulsa’s prepare for the city’s potential.

“City engineers recognized we needed to look at the future and how Tulsa was going to develop,” McCormick said.

That vision has paid off for Tulsa residents. The Class 1 FEMA rating saves Tulsans 45% on insurance through the National Flood Insurance Program. And the city’s floodplain map keeps buildings farther from flood risk, even as the city grows. Although some of the city’s businesses suffered losses in the 2019 floods, no homes were destroyed.

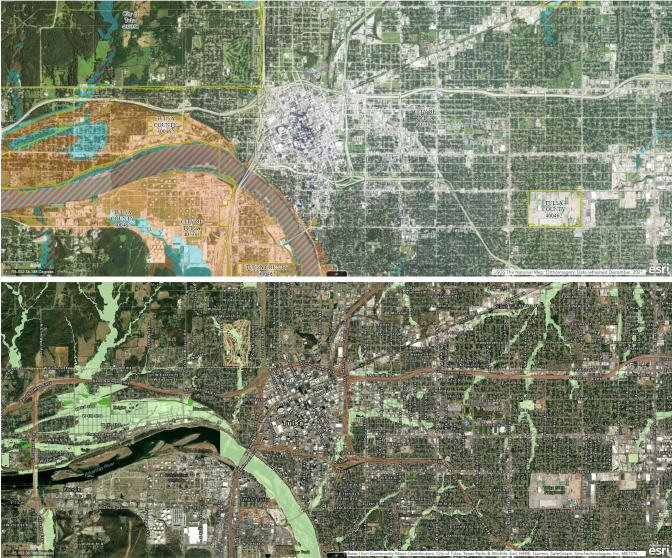

Graycen Wheeler/OPMX

The top panel shows a section of FEMA’s National Flood Hazard Layer Viewer; areas marked with blue and red stripes denote FEMA’s regulatory floodplain. The bottom panel shows the same section from the City of Tulsa’s Floodplain Map; light green denotes the city’s regulatory floodplain.

Decades of flood preparations put to the test

In late May of 2019, storms dumped between 10 and 16 inches of relentless rainfall on most of northeastern Oklahoma. Much of that water made its way where it’s supposed to go — flood control reservoirs.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers operates 38 flood control dams across the state, many of them in northeastern Oklahoma. They collect runoff and control the flow of the excess water down Oklahoma’s rivers.

David Williams, the chief hydrologist for the Corps of Engineers Tulsa District, estimated flood control reservoirs saved Tulsa County around $1.8 billion in damages during the 2019 floods.

The Corps of Engineers also helps maintain Tulsa’s levees, which keep water within the river’s banks even when it’s flowing high and fast. By 2019, it had been decades since the levees had seen so much water.

The Army Corps’s engineers stood by, along with hundreds of National Guard members who patrolled the levees.

“What you need are eyes on the ground,” Williams said. “Because if you can identify areas where a problem has occurred or is occurring, you can address it before it becomes a full failure.”

Because the Corps and its collaborators found problems so quickly, the levees held.

“We have disasters that define us, and this is one of those for me,” said Annie Vest, a hazard mitigation expert who’s worked on flood planning with government agencies and on her own for decades. “We had so much data, and we were ready for it in the City of Tulsa.”

But even with all the safeguards working as they should, businesses still suffered.

The Muscogee Nation owns the River Spirit Casino in Tulsa, which sits on its land next to the Arkansas River. The casino saw over a yard of water in its parking garage and up to a foot in the building.

The resort resumed operation after a month of recovery. But Bobby Howard, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s director of emergency management, said the Nation is working to brace for future flooding. The tribe is investing in flood infrastructure and developing temporary measures it can take when waters start to rise.

“Using that battle sheet and working with the Corps [of Engineers], we could protect the facility to about 10 feet above where the water was in the 2019 flood,” Howard said.

The tribe’s flood preparations at River Spirit will cost around $30 million but Howard said they’re worth it.

“You have to do it to protect your investment and to protect the citizens in that whole area,” Howard said.

But while some communities are working to protect their investments against future flooding, individuals in Tulsa and Sand Springs are asking themselves, is flood insurance worth it?

‘A tax on low income people’: Navigating the waters of flood insurance

McCormick said more and more residents are choosing not to get flood insurance — a situation he says likely stems from people wholly trusting the city’s mitigation measures.

Just down the road in Sand Springs, there’s also been a downturn in residents buying flood insurance — but for a completely different reason.

Beau Wilson works as an insurance agent in Sand Springs and is also the city’s vice mayor. While his home wasn’t affected by the 2019 flood, he had to evacuate his grandparents from their house, hours before it was submerged up to its roof.

“If your flood and homeowner’s insurance is $3,000 collectively, and then you have property taxes at $1,200 or $1,300 — for a community that’s probably lower income, that effectively works as a tax on low income people,” Wilson said. “The government can come in and raise the rates however they want. And so that, in my estimation, is looked at as a tax on people that aren’t in a place to pay for that.”

While getting people to buy flood insurance may be an uphill battle in Sand Springs, the city is investing in more preventative infrastructure, like raising its pump stations and installing a new flood siren system.

Buying in to a buyout

Infrastructure and planning can protect people during future floods, but those who have already lost their homes have fewer options. In some cases, the government will offer to buy out damaged or flood-prone properties. But while the need is high, the funds are limited.

Sand Springs, which is located in Tulsa County, is utilizing another tool: the county’s plan to buy out residents from their flood-prone homes. But federal funding for the program only goes so far.

Deputy Director Joe Kralicek of the Tulsa Area Emergency Management Agency said while there are over 170 properties that need to be targeted, there are only enough funds to buy out 50-60 of those homes. Kralicek said he’s brought in national experts to help prioritize which homes to buy.

“My fear is that something goes wrong and we don’t ever get a chance to do this again,” Kralicek said. “And so we want to make sure that we’re doing this absolutely right.

Buyout programs can be an effective way to mitigate future destruction from severe weather events, but some iterations of the process have been criticized for unfair market practices, gentrifying neighborhoods or being too difficult to access.

Kralicek said valuations on properties will be determined based on its fair market value, pre-disaster. Residents can also receive relocation assistance.

“We want to make sure that when people leave, they’re not in a worse situation,” Kralicek said.

But the federal program takes years to implement. In the meantime, residents like Chuck Graham are waiting to see if they’ll be one of the lucky few picked for the buyout. He put his name on the list to be considered, but was told it would be 3-4 years until something would happen.

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

Chuck Graham stands in front of his Sand Springs home. Three and a half years later, the Grahams are still waiting to know if they’ve been chosen for the buyout.

Flood buyout programs are becoming more frequent across the country. And as climate science continues to reveal more troubling predictions for the future, local governments will likely be responding to more serious and more frequent severe weather events.

The ‘big, big problem’ ahead

In May 2019, the National Weather Service office in Tulsa issued over 1,500 flood watches or warnings. Many of those were for flash flood events, which happen quickly when heavy rains overwhelm low-lying areas.

The U.S. will likely see more flash flooding as climate change progresses, especially in the central part of the country. A research team led by Yang Hong from the University of Oklahoma modeled how increased temperatures from carbon emissions would affect rainfall and flooding. Higher temperatures lead to more water that’s stored in plants and soil ending up in the atmosphere.

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

Professor Yang Hong stands in front of his office bookcase in the National Weather Center in Norman.

”Doesn’t mean it’s necessarily all going to fall out at once, but you have this potential riding around in the atmosphere,” explained JJ Gourley, a researcher from the NOAA and the National Severe Storms Laboratory. “And then if the conditions become right, it can turn into a big, big problem and cause flooding.”

The research found flash floods will rise more quickly. The floodwaters will swell higher and cover a larger area. And the flooding season in the central U.S., which normally peaks in May and June, will creep into other seasons.

“We need to update our infrastructure — not just new infrastructure, but more climate-resilient, flooding-resilient infrastructure,” Hong said.

As climate change continues, the United Nations projects social inequality will create even bigger gaps in how communities fare during disasters. That means rural communities and historically marginalized groups of people may not have the resources to implement preventative infrastructure or may be left to take care of themselves in the face of disaster.

In 2019, one of those communities was Braggs, Oklahoma.

Saving Braggs Island

In the rolling, green hills of eastern Oklahoma sits the tiny farming town of Braggs, with a population of about 300 people. The town, which spans just over a quarter of a square mile, backs up to the Army National Guard training facility Camp Gruber. It also sits right beside the Arkansas River.

In May 2019, Braggs resident Roger Moore watched the water slowly rise around his town over the course of a few days. Soon enough, the small — and fortunately slightly elevated — community found itself surrounded by floodwaters, blocking every way out.

“We became an island,” Moore said.

Courtesy of Braggs resident.

May 2019 flood waters creep toward a Braggs house. The waters came just feet from the house, even though the river is past the treeline.

The few places in town with food — a malt shop, a gas station and a bar — quickly ran out. Over the course of the next few days, Moore’s community would band together to take care of each other, as the outside world figured out creative ways to get supplies into Braggs.

“Ultimately, we served I think somewhere around a thousand meals in those days,” Moore said. “We had people that were bringing in all of their hamburger meat that they had at home and said, you know, ‘Here. We can replenish ours later.’ … We just took care of each other.”

Moore said he felt like the town was well-taken care of by emergency responders during the disaster, but isn’t sure what this small, local government can do in the meantime to bolster flood protections — or where that money would come from. He said he doesn’t see many tools in the preventative toolbox other than potentially maintaining an access road out of Braggs.

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

Braggs resident Roger Moore found himself in charge of feeding hundreds during the May 2019 flood. Moore still volunteers at his local American Legion.

And that’s where smaller local governments like Braggs and Sand Springs find themselves in preparing for a wetter future — implementing a checkerboard of affordable measures with limited impact.

“I think your [state and national elected officials] focus on the population centers, which is natural. I mean, that’s where the most people are,” Sand Springs Vice Mayor Beau Wilson said. “But I think we need to look out for our rural communities. And Sand Springs isn’t that rural, we’re only eight miles away. But I do get the feeling that sometimes we’re kind of the stepchild out here.”

The Army Corps of Engineers will aid smaller governments that ask for assistance in making better flood plans, David Williams said. But amid the backdrop of climate change accelerating the shift to more unpredictable and severe events, residents’ levels of access to flood protections in Oklahoma boil down to one factor: their zip code.