Why Flood Insurance Is Likely Going to Cost More in Texas

Mose Buchele

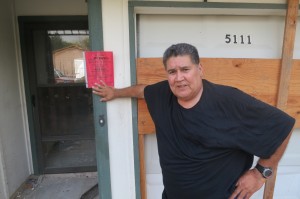

Richard Rivera stands in front of a red sticker that marks his house as "uninhabitable" due to recent flooding.

It’s been three weeks since a flood swept through Richard Rivera’s Austin, Texas home. There’s still a dead car, washed up by the waters, deposited on his front yard. A crack has formed on his concrete driveway. A result, he says, of the deluge. He doesn’t know where his air conditioning unit floated off to. His home bears the red sticker, left by city inspectors, that deems it uninhabitable.

But unlike many of his neighbors, Rivera can take solace in the fact that he was prepared. He paid about $2,000 annually for flood insurance.

“You pay it, and you pay it, and pay it, and hopefully you never need it, but when you need it, you’d like to have it,” he says with a rueful smile, standing in the wreckage.

In a decision he now looks back on with some degree of awe, Rivera had increased his insurance coverage just months before the flood, expanding it to cover an additional $60,000 in damages.

Around the same time, he says, his neighbors dropped their insurance altogether.

“He got laid off and his wife got laid off. “That was one of the deals where the payment was about as high as the mortgage so he let it go,” Rivera says.

“That guy is really having some problems right now” he adds. “They’ve got kids.”

There’s a growing concern that more people will find themselves in the situation of that neighbor if changes to the National Flood Insurance Program move ahead.

Flood insurance is administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). That’s because private insurers wouldn’t offer coverage to some homeowners without the backing of the government, says Professor David Maidment, head of the University of Texas Center for Research in Water Resources.

“After Hurricane Katrina, the Federal Flood Insurance Program took a huge hit,” he says, “and it’s now $24 billion dollars in the hole.”

To fix that, Congress came up with an overhaul of the program, called the Biggert Waters act – after its two Congressional authors. It passed in 2012 and began to take effect last month.

“[The law] was designed to bring more money into the flood insurance program by eliminating subsidies for flood insurance, and having people pay premiums that reflected the real risk of having them incur flood losses,” says Maidment.

That means people who had received subsidies will start paying more.

Around twenty percent of all policy holders nationally receive government subsidized insurance. Over 60,000 of those policyholders are in Texas. And FEMA says there are many different categories of policyholders who will see a price increase.

“It could change if there’s a flood, it could change if you’re policy lapses, it could change if you sell your home and somebody get s a new policy, it could change if this is a business property and this is not your primary residence.” Kevin Shunk, Floodplain Administrator for the City of Austin says. “There are a lot of reasons this could change.”

Some of those increases will be gradual, with smaller price hikes every year. Some will be immediate. For example, if you bought under the old rules in the year after Biggert Waters passed, you will immediately pay more under the new system.

“I’m talking thousands of dollars of difference,” says Shunk. “Maybe flood insurance policies for below the hundred-year flood plain may be on the order of $15,000 a year, whereas before maybe it was 2,000 a year.”

So City and State official are advising people to contact their insurers.

“I just want to make sure that people who have a flood policy, don’t let it lapse,” Patty Lapshaw a VP with the insurance company Wright Flood says. “Because if they let it lapse, they’re gonna be affected with full risk rates as well. They’ll lose their subsidies.”

Lapshaw says the consequences of Biggert Waters have been “confusing” for many insurers. (Lawmakers also appear to have been caught off guard by the steep increase in cost). Like many others, she advocates an overhaul of the bill to make the impact less severe, and perhaps more gradual on some policyholders. Though she’s concerned that the overhaul of Biggert Waters (itself an overhaul of the original flood program) could lead to even more confusion if not done right.

A vote on postponing some price hikes could come in the US Congress within days.

On Tuesday at a meeting of the House Committee on Financial Services, legislators heard from another group that would like to see that postponement: realtors. They worry that high flood insurance rates could make some properties unsellable.

“That’s the concern with flood insurance, as it is with lots of other costs of homeownership, is that we want to be sure there’s not specific and targeted barriers to homeownership,” Emily Chenevert with the Austin Board of Realtors, says.

Of course, supporters of the new system argue that that’s the point. They say home ownership in areas at risk of dangerous flooding should be discouraged. And higher insurance rates eventually will be necessary.

In the case of Richard Rivera, the flooded homeowner, he doesn’t think he’ll have much luck selling his property either way.

“Would you like to buy this house, especially with what happened to me?” he asks. “No, you wouldn’t! Especially if you got little ones.”

For the time being he’s just recovering what he can, and trying to decide where to re-build once his insurance claim is finalized.