A Killer of Bats Inches Towards Texas

Photo by Al Hicks, NY Dept of Environ. Conservation.

A little brown bat found in a New York cave exhibits fungal growth on its muzzle, ears and wings.

Before Winifred Frick enters a bat cave in Wisconsin, she and her colleagues strip to their underwear and wipe themselves down with Lysol. When they leave, they bag everything up and wash it with Lysol as well.

“Spores can definitely get on peoples’ boots or pants or whatever, so it’s been really important that cavers, as well as researchers, do decontamination,” Frick, a bat researcher and adjunct professor at UC Santa Cruz, says.

She’s talking about the spores of a fungus that’s responsible for the deaths of millions of bats. It’s the cause of “white-nose syndrome,” so-called because of the white growth that appears on the noses of infected hibernating bats.

Researchers are still unclear about how the fungus kills bats, but it appears to wake them from hibernation, leaving them malnourished.

“They’re also finding that these bats are incredibly dehydrated,” says Ronald Van Den Bussche, Professor of Zoology at Oklahoma State University. “They’ve seen bats up in the Northeast licking snow and licking ice. It’s a combination of starving to death and de-hydration.”

And it’s spreading, transported by bats, cavers or even careless scientists. That leaves those in the South and West to wonder, “What will happen when white-nose syndrome gets here?”

“We’re really concerned with the Ozark big-eared bats,” says Van Den Bussche. “There’s only about 1,500 left. Where white-nose syndrome has shown up in North Central Arkansas is also a place where [they’re] found.”

Gone to Texas?

Different bats appear to react differently to the fungus. That could be good news for some Texas species like the Mexican free-tailed bat.

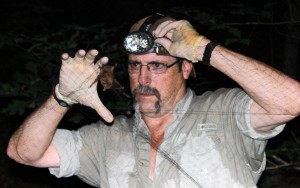

Photo courtesy of Ronald Van Den Bussche

Ron Van Den Bussche is concerned what white-nose syndrome could mean for some bats in Arkansas.

“You know, I don’t think it’s going to impact those populations,” says Van Den Bussche.

White-nose syndrome seems to attack bats when they are in a deep torpor, a time when their immune response is compromised. Free-tailed bats like the kind that live in a vast colony under the Ann Richards Bridge in downtown Austin migrate between Texas and Mexico. They never truly hibernate, so they may be spared.

But the same isn’t true for some other Texas species.

“The species up in North Texas that they’re looking at, like the cave myotis and tri-colored bats, those are true hibernating species,” says Frick.

Because the fungus impacts different species in different ways, scientists are also studying which bat populations may actually increase as the syndrome moves through a region.

“As certain bat species are removed from the landscape by white-nose, the bat species that remain, we’ve been documenting how they rush in to fill that empty niche,” says Mark Ford, a researcher with the United States Geological Survey based at Virginia Tech. “It’s very real, and it’s very apparent, and it probably will have profound ecological implications.”

Photo courtesy of the USGS

Dead bats litter the floor of a cave in Vermont. Some researchers believe bats in warmer climates could fare better when faced with white-nose syndrome.

Some researchers believe southern states may be saved form those “ecological implications” simply because of their mild winters. Van Den Bussche says that Texas bats — even if they do hibernate — could fare better if infected with the fungus.

For one thing, the fungus takes weeks to grow on a hibernating bat, and bats in the South don’t hibernate for long periods of time.

Secondly, they’re less likely to starve if they wake up.

“I know here in Oklahoma, except for the real coldest part of the winter, the rest of the year we see moths and other insects out. Which is a food source,” he says.

A Clue in the Ancient Past

Every researcher who spoke to me was quick to highlight how little is still understood about the toll white-nose will take, even in the Northeast where it’s been most active. But there does appear to be one possible clue, far across the Atlantic.

“It’s pretty much accepted now that the fungus came from Europe,” Dr. Lynn Robbins at Missouri State University, says.

Photo by Mose Buchele

Mexican Free Tail bats leave the Ann Richards Bridge on their nightly hunt. Odds are these bats will resist the fungus. Many of them winter in Mexico where they do not hibernate deeply.

The theory is that the fungus was brought over to caves in New York State by a human visitor some time around when it was first discovered. That begs the question: If white-nose exists in Europe, why aren’t bats in Europe dying?

“We don’t know,” says Dr. Robbins. “It may have come through [Europe]10,000 years ago when nobody was noticing.”

The bats that survived that event may have developed something – a new diet, a habit or an immunity – that protects them.

“They may have lost large numbers of bats in the past, and these are the species [in Europe now] that were not as heavily impacted. We don’t know if the bats may have changed their roosting habitats,” says Robbins.

And if some bats in Europe found a way to survive the plague of white-nose syndrome, could the same thing happen here?

“We hope so,” says Robbins. “We hope that the bats will somehow develop an immunity. Those that survive will able to better cope with this fungus. But we just don’t know.”