Life By the Drop: A Tale of Drought Told in the Flow of the Colorado

Photo by Terrence Henry

The Colorado River winds it's way near the town of Robert Lee. The town's reservoir dried up last year and water is now pumped in by pipeline.

Running from headwaters near New Mexico, the Colorado cuts southeast through Texas, feeding cities, farms, power plants and ecosystems before flowing into the Gulf of Mexico. It’s the longest river to start and end all within the state of Texas.

Running from headwaters near New Mexico, the Colorado cuts southeast through Texas, feeding cities, farms, power plants and ecosystems before flowing into the Gulf of Mexico. It’s the longest river to start and end all within the state of Texas.

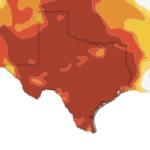

In good years, its water is enough to sustain communities at every point as it cuts its course through the state. 2011 was not a good year.

To hear the voices of people who depend on the Colorado for their lives and livelihoods is not just to hear about the drought of 2011. It teaches us about the looming water crisis that faces Texas. If trends continue, our state will keep growing but our water supplies will stay the same, or even diminish.

Taken individually, each stop along the river puts a human face to last year’s drought. Taken as a whole, the stories paint a picture of competing interests and a state struggling to manage a limited but vital resource.

Running Dry in Robert Lee

In West Texas there sits a reservoir that isn’t. The E.V. Spence reservoir was built in 1969 to protect communities from just the type of catastrophic drought that hit the state a decade earlier. It worked, until last year. What had been a stable water supply turned into a muddy pit carved out of the high plains, and the town of Robert Lee had to find other ways to stay alive.

The story of Robert Lee is one that played out in other small towns across Texas last year, like Groesbeck and Spicewood Beach. Rivers and reservoirs dried up.Wells failed. And city governments with little cash rushed to finance lifelines.

For John Jacobs, a fourth-generation West Texan and lifelong resident of Robert Lee, the moment his town almost ran dry was actually a long time coming. But it still felt sudden. The town had brushes with running dry before. “But every time we’d go get in a bind, it would rain,” Jacobs remembers. “We’d catch water, and then we’d spend all that money for something else.”

Then came the great drought.

High and Dry on the Highland Lakes

As the Colorado flows southeast it fills one of the most extensive reservoir systems in Texas. The Highland Lakes feed Hill Country communities, the booming urban population in Austin and communities and farms downstream. They’ve also become an attraction in their own right.

Over the years, more and more communities have sprouted up along the shores of the lakes, attracted to stunning vistas and clear waters. People here see the reservoirs not just as water supplies, but as something to be enjoyed in their own right.

Then, last year, the lakes began to dry.

By early 2012 you’d likely find yourself stepping on gravel, fish bones and fresh-water clam shells while walking the dry river and lake beds. Water wells in the area also began to fail. That happened most noticeably in Spicewood Beach, where the Lower Colorado River Authority (LCRA), the agency that owns the well, needed to haul water in by truck for the people who live there.

Earlier this year, when the LCRA had started hauling water into town and constructing a long-term water storage system, town residents Robert Salinas and Martin Peterson happened to be on their lunch break. As the two men watched the LCRA at work they speculated about what went wrong, and whether things will ever get better.

A Growing Thirst in Austin, Texas

During roughly the same time frame that Texans endured the worst single-year drought in the state’s history – Austin, a city that depends on the Colorado River for its very existence – was the second fastest-growing city in the U.S. In fact, six of America’s ten fastest growing large cities are found in Texas.

Like many of those places Austin ramped up its conservation during the drought. It strictly limited outdoor watering and other major water intense practices. At the same time, the city undertook a controversial new water treatment plant project to meet its growing needs – needs that some groups said could be answered with more conservation.

Finally, the city fought for changes in how water along the Colorado River is managed. Many in Austin watched in near disbelief as water from the Highland Lakes was diverted downstream to agricultural interests at the height of 2011 drought, It was an experience that prompted the city to supported a new water plan for the region.

As Greg Meszaros, head of Austin’s Water Utility, told StateImpact Texas, “we pay almost 20 times as much per gallon of water compared to agriculture, so we work to make sure we get the full benifits of the water we paid for.”

Farming When the Water’s Cut Off

2011 was not only Texas’ worst single-year drought. By a strange twist of fate, it was also the year the state formed its new long-term water plan. Some planners viewed this as a blessing-in-disguise: as least the drought was raising awareness of water issues.

The planning process forced some hard questions: what role will agriculture play in the future of Texas? Should Texans continue to raise water-intensive crops like corn and rice?

Currently, more than half of the state’s water resources go to agriculture. Much of what’s left of our untapped supplies exist in rural parts of the state, far from population centers. For cities to have enough water in the future, state planners estimate that agriculture, especially water-intensive agriculture, will have to cut back.

Those cuts were already forced this year in the lower regions of the Colorado River, where rice farmers were not given water stored in the Highland Lakes, to ensure that reservoirs upstream remained adequate for population centers like Austin.

The cut-off was an extraordinary measure prompted by the drought. It was the first time in the history of rice farming in southeast Texas that they weren’t given water. But it could serve as a preview of things to come.

Now, rice farmers like Ronald Gertson are fighting upstream interests over the area’s regional water plan. At issue: how low do reservoir levels have to go before the water is cut off again.

Where the Colorado Meets the Gulf

The view of the drought is different standing on a boat off the Coast of Texas. When you hear the cries of seagulls and the steady roll of the surf you would be forgiven for thinking that nothing is wrong. But as last year’s drought pushed through the summer, the Colorado brought less and less fresh water into the Gulf of Mexico.

In Matagorda Bay, where the river empties into the sea, the water quality suffered. Oyster harvesting was shut down and fishermen reported fewer crabs and fish in the bay.

With more and more interests competing for Colorado water, including rice farmers, a booming upstream population, and a coal-fired power plant project, some worry that fresh water scarcity could become the new normal.

That’s the fear of Captain Jerry West, a fishing guide in Matagorda Bay.