Life By the Drop: Running Dry in Robert Lee

Photo by Terrence Henry/StateImpact Texas

John Jacobs, Mayor of Robert Lee, says drought is "like a cancer."

It wasn’t until recently that John Jacobs started sleeping well again. The mayor of Robert Lee, a West Texas town of some thousand people, has spent the last few years grappling with the same issue facing all of Texas: How to find water for our people.

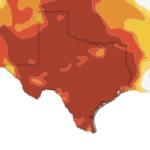

The great drought of 2011 was the driest and hottest period on record in the state. But it crept in slowly. “Drought is like a cancer,” Jacobs says. “It just slowly eats and eats and eats. Your water sources dry up, your businesses start drying up. Without water, people aren’t going to stay there. It’s just a slow, declining death.”

The story of Robert Lee is one that played out in other small towns across Texas last year, like Groesbeck and Spicewood Beach. Rivers and reservoirs dried up. Wells failed. And city governments with little cash rushed to finance lifelines.

The story of Robert Lee is one that played out in other small towns across Texas last year, like Groesbeck and Spicewood Beach. Rivers and reservoirs dried up. Wells failed. And city governments with little cash rushed to finance lifelines.

For John Jacobs, a fourth-generation West Texan and lifelong resident of Robert Lee, the moment his town almost ran dry was actually a long time coming. But it still felt sudden. The town had brushes with running dry before. “But every time we’d go get in a bind, it would rain,” Jacobs remembers. “We’d catch water, and then we’d spend all that money for something else.”

Then came the great drought.

“We knew we were getting in serious trouble about two years ago,” Jacobs says. From November 2010 to October 2011, San Angelo, the nearest city with weather records, received less than six inches of rain. An average year is more than 21 inches. The sole source of water for the town, the EV Spence reservoir, where Jacobs used to fish and camp growing up, dropped to less than one percent of its capacity. As the reservoir shrank, the water that was left became too salty for drinking. “We were using it,” says Jacobs, “but it was just toilet and bath water. You couldn’t buy a soap that would lather in it.” Locals had to buy drinking water from San Angelo.

Now the reservoir is little more than a river valley. You can drive your truck, as Jacobs does on occasion, far below where the water line is supposed to be. As he motions toward the pump that once served the town, a bull snake crosses his path. “What you see is what water’s left,” he says, pointing into the distance. “Right now it’s just a bunch of salt cedar and tumbleweeds, with a blue thread running through it.”

The town started looking in earnest for water two and a half years ago. The best option would have been to secure a groundwater source, but there wasn’t time. They cobbled together some grants and loans from the Texas Department of Agriculture and Water Development Board and set about building an emergency pipeline that would bring water twelve miles from the town of Bronte, which is nearly equal in size to Robert Lee.

It took six months and $2.8 million to build it. The whole town pitched in to do labor, from high school kids to “some fairly senior citizens,” Jacobs says. Everyone helped to dig a stretch of the line. “There were a few, believe it or not, rainy days where we couldn’t work,” Jacobs remembers with a chuckle. “Fighting the drought and running out of water and we couldn’t work for rain.”

Photo by PBS NewsHour

Robert Lee's pipeline to Bronte, twelve miles away, cost $2.8 million to build.

Just a few weeks ago, on May 22, the pipeline kicked into gear, and Jacobs got to sleep. “That’s the first night I slept all night in a long time. You don’t think about it until the time gets tight, but your decisions have a lot to do with the lives of lots of folks.” He pauses for a moment. “Most folks here have been lifelong friends. It’s hard to look them in the face and tell them they can’t use any water. It’s been a tough two years, but we’re getting through it.”

The pipeline is a band-aid, says Jacobs, as the town is still looking for a permanent groundwater solution. They’ve had to increase taxes and water rates. And he worries about more than just Robert Lee. “The rainfalls have quit and the population has grown,” he says. “So far this has been a relatively short drought, but we don’t know when it’s over. It’s certainly not over yet.”

“Numbers count,” Jacobs says. And for small towns like Robert Lee, at the pinch point of limited supplies and money, he suspects big cities will win when it comes to water. “Realistically, in their eye,” he says, “these thousand people can move overnight.”