The Race to Save the Pronghorn of Far West Texas

Photo Courtesy of Dr. Louis Harveson.

Death has been stalking the Pronghorn of West Texas Their numbers have dropped dramatically in the last five years, leaving people wondering if the species will continue in the region.

If you think pronghorn don’t hold an iconic place in the story of the old west, consider the lyrics to the tune Home on the Range. Remember, “where the deer and the antelope play?”

Those “antelope” you’ve heard about your whole life weren’t really antelope at all. They were pronghorn.

The confusion started with European settlers who mistook them for the old world species. In fact, the pronghorn is a uniquely American creature. The the fastest land mammals in the Western Hemisphere, they are the second fastest in the world after the cheetah. They evolved that way to out run a long-extinct species of North American Cheetah.

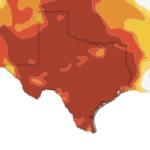

Pronghorn once roamed Texas from the Hill Country all the way to the state’s western tip. Today, though they still maintain healthy populations in many parts of the Midwest, their range in Texas is diminished to the point of disappearing.

“The Trans-Pecos region of far West Texas and the Panhandle, really are the strongholds of pronghorn in the state. So habitat fragmentation, brush encroachment, all these things, basically have forced them really to the last refuge in West Texas.” Dr. Louis Harveson, Director of the Borderlands Research Institute at Sul Ross University, told StateImpact Texas.

Harveson says about five years ago people in that “last refuge” in the Trans-Pecos, where around 17,000 pronghorn once roamed, noticed the animals were disappearing there too.

“We really couldn’t figure out what was going on. The animals were really just dropping dead in the field. It wasn’t predation or anything, they were just dying,” he said.

In 2008 alone, as many as 3,000 pronghorn died. The population in far West Texas now stands at around 4,000 animals total. Those numbers are still dropping. No one’s sure why, but a coalition of scientists, hunters, and conservationists called the “Trans-Pecos Pronghorn Working Group” have found elevated numbers of a blood parasites and a general malnutrition in the species. The extremely dry weather has also contributed.

Experts like Harveson says the grasslands themselves may be sick and that the animals are simply suffering the consequences. “So we’re trying to figure out a way to reverse that,” he says.

A Failed Restoration

Photo by Dr. Louis Harveson.

Helicopters and net guns were used to relocate pronghorn from the Panhandle to the trans pecos region.

Last year, Texas Parks and Wildlife moved 200 pronghorn from the Panhandle, where their population remains stable, to far West Texas.

But they arrived just in time for the 2011 drought.

“We got dealt a horrible hand: drought, heat, wildfires, everything but waves of locusts have come down to West Texas and made this a very difficult year for restoration,” said Harveson.

Eighty percent of the transferred animals that researchers kept track of died over the following year. Now, Parks and Wildlife has put all restoration projects on hold until the drought ends.

Lessons in Drought and Fire

Even though the impact of the drought and accompanying wildfires was devastating to the pronghorn, researchers say the conditions have also provided unexpected insights into the what might help the animal thrive.

Driving through the ranch lands outside of Marfa, resource management graduate students Justin Hoffman and John Edwards discuss the great Rock House wildfire that scorched over 300,000 acres of land in the region last year. They say the bones of long-dead pronghorn shone white on the blackened grassland for weeks afterwords, but the fire could prove to have its benefits.

Photo by Mose Buchele for StateIMpact Texas.

Justin Hoffman (left) and John Edwards study resource management at Sul Ross University.

Hoffman says he has two pronghorn radio-collared that survived the blaze, but never left the burn zone. He has no idea what the animals are eating, but “there must be something about fire” that is actually good for the animals, he speculates.

On their drive they encounter a second way the blaze may have helped.

A young pronghorn, one of the few that’s managed to survive in recent years, is running between the dirt road and a new fence that’s been put up since the wildfires. The animal seems spooked. and as Hoffman slows down to observe, it ducks under the specially designed fence and makes its escape.

“These are all pronghorn-friendly fences that they implemented after the burn,” he says with a note of satisfaction. “Unfortunately [the ranchers] lost a lost of infrastructure, but they opened up a lot of country for those pronghorn to move around.”

Landowners interested in installing pronghorn-friendly fences have been helped by federal and state programs that defray the cost of installation.

“One really good program that we’ve had is the National Resources Conservation Service equip program, so a landowner can put in pronghorn friendly fences, brush control, improving water distribution,” TPWD’s Shawn Gray told StateImpact Texas. “And at Parks and Wildlife we actually have a similar program called the Landowner Incentive Program.

For many of landowners it makes economic sense to encourage pronghorn. Landowners can make money selling hunting leases in West Texas to sportsman eager to bag a pronghorn, but permits to hunt the animals have disappeared along with the pronghorn themselves. Landowners who control large tracks of land with herds of the animals used to get dozens of permits a year to hunt bucks, these days they’re lucky to get one or two, Louis Harveson told StateImpact Texas.

Faith in the Strength of an Ancient Species

“The pronghorns been here thousands of years, this is not new. These droughts have happened before, may have been more severe, they survived through that,” says Albert Miller, sitting in the County Jailhouse in Valentine, Texas.

Miller is a lifelong rancher in Jeff Davis County, he’s met me at the empty jailhouse because it’s one of the few centralized meeting spots in this sprawling region.

Photo by Mose Buchele

Albert Miller is a lifelong rancher and County Commissioner in Jeff Davis County, he's trying to encourage a pronghorn population on his land.

He is an example of what people in the Pronghorn Working Group would like to see more of, a rancher whose amenable to trying new land management techniques to encourage the pronghorn population. Two fawns were born on his land last year, even in the worst of the drought. And though he can’t shake the idea that all the efforts to save the pronghorn amount to pointless “meddling,” he says he plans to leave some of his land ungrazed by cattle for the pronghorn.

In fact, Miller wonders if the drop-off in cattle in West Texas might help the wild animals. Ranchers like him had to cull their cattle herds to nearly nothing last year. That meant “less competition for forage,” says Miller.

But despite these signs of hope, the die-off continues. And more pronghorn won’t be relocated to the area until the drought breaks, leaving preservationists to wonder if there will be any pronghorn left in far West Texas when the clouds return to their home on the range.