Rice Farmers Used More Than Three Times as Much Water as Austin Last Year

Photo by Jeff Heimsath/StateImpact Texas

Rice farmer Billy Mann says that in the future, they'll have to grow more rice with less water.

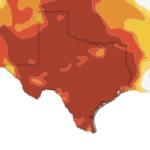

New numbers put into perspective just how much water rice farmers in southeast Texas used out of the Highland Lakes for their water-intensive crop compared with city-dwellers in Austin last year. The Highland Lakes consist of two large reservoirs, Lakes Buchanan and Travis, and several pass-through lakes. Buchanan and Travis are still only half-full, despite a wetter-than-average winter.

A new report from the Lower Colorado River Authority (LCRA), which manages water in the Highland Lakes for the city of Austin and farmers downstream, shows that rice farmers used 367,985 acre-feet of water from the lakes in 2011. (An acre-foot is a measurement of water, i.e., how much water it would take to cover one acre with one foot of water, which is roughly equivalent to 325,800 gallons.) Another 65,266 acre-feet of water was released from the lakes downstream but not used, due to evaporation, seepage, or “conditions changed that eliminated the need for the water,” according to the LCRA, bringing their total to 433,251 acre-feet used from the Highland Lakes.

The city of Austin, on the other hand, used 106,622 acre-feet of water from the Highland Lakes, less than a third of the amount used by rice farmers. And the same pretty much holds true for previous years. (Another 192,404 acre-feet of water straight up evaporated from the lakes last year.)

So why do rice farmers get to use so much water, when some towns are running out?

Rice farmers downstream on the Lower Colorado will tell you it’s because they were here first.

“In a sense it’s our water,” Haskell Simon, a rice farmer and representative of the industry in Matagorda County told StateImpact Texas earlier this year. “In order to give a more assured supply of water for that burgeoning industry, there was a pressure to develop those storage facilities which are now the Highland Lakes,” he said. Texas water laws can be confounding, but in the case of the rice farmers it essentially boils down to this: they were here first, so as long as there is enough water around, they get to use it for their crops.

The LCRA says as much on their website:

“According to state water law, first in time is first in right. Downstream rice farmers were given first water rights in the Colorado basin, and these rights are senior to LCRA’s water rights for the Highland Lakes. In fact, without the support of the rice farmers, the Highland Lakes and dams might never have been built. Rice farmers were among the strongest supporters of building the Highland Lakes and dams in the 1930s. They recognized the value of the dams in easing flooding and making water available during droughts.”

“At the time that our water rights system was created, there was not only no one living on these lakes, they [the lakes] weren’t here… so the water flowed down to rice farmers on the southern part of the basin and they got all they needed,” Andrew Sansom, executive director of the River Systems Institute at Texas State University, told PBS NewsHour earlier this year in an interview published by StateImpact Texas. “Today, the economic engine gendered by recreation, residential growth, and tourism up on [Lake Travis] far exceeds the [size of the] rice industry, and so there is a pitched battle underway as to who should get the water and it’s going to get worse. Essentially, we’re struggling with a system [created] hundreds of years ago… and bears no resemblance to what we look like [today].”

Rice farmers not only use much more water than Austin, they also pay less for it. That’s because their supply is “interruptible,” meaning that if the amount of water in the Highland Lakes reaches a certain level, they’ll be cut off. But that’s never happened until this year.

On March 1st, under the guidelines of an LCRA emergency drought plan adopted last fall, the authority cut off water to the rice farmers downstream in Matagorda, Wharton and Colorado counties because there wasn’t a enough water in the lakes. They were about a billion gallons short. And under a new water plan currently under review by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), they’ll be less likely to get water in the future, especially during dry years like 2011.

You can read the full LCRA report here: