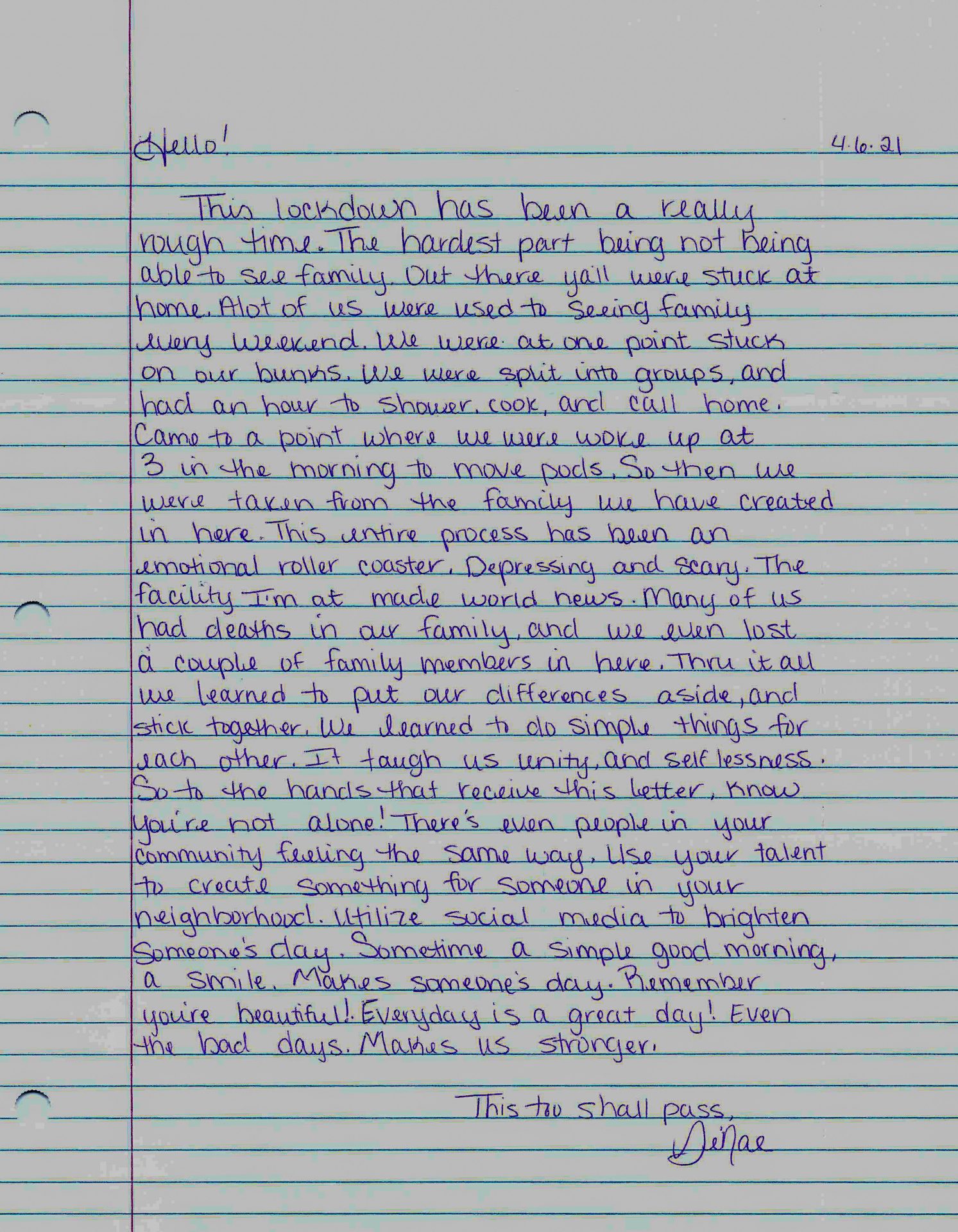

Se'Nae Starnes' letter offers simple advice on making it through the pandemic a day at a time.

Courtesy Poetic Justice and Se'Nae Starnes

Se'Nae Starnes' letter offers simple advice on making it through the pandemic a day at a time.

Courtesy Poetic Justice and Se'Nae Starnes

COVID-19 built new walls that further isolated Oklahoma’s prisoners from the rest of the world.

It started last March. The Department of Corrections turned away visitors. Prisoners began losing access to outdoor space and they could no longer go to classes and common areas. The changes were safety precautions.

Se’Nae Starnes has young children and before the pandemic she was already limited to seeing them on the weekends. She says when COVID-19 hit even that was taken away.

“Like, my daughter especially, she’s not able to write and read and be able to communicate that way,” Starnes said. “So we have to be creative and draw pictures because we weren’t always able to get to the phone.”

Starnes is incarcerated at Eddie Warrior Correctional Center in Taft. The Department of Corrections allowed prisoners’ friends and family to come back more than two months after stopping visits.

Then the agency suspended visitation again in late September when COVID-19 cases in the prison system were increasing rapidly. That final suspension was lifted for most prisons, including Eddie Warrior, in April of this year.

Despite the dangers of COVID-19 and prison limitations, 470 incarcerated women used a long distance writing program to connect with people outside prison walls.

The women and their writing partners helped each other get through the pandemic.

Last month, participants wrote letters and poems meant to help people who were having a hard time coping with the harsh realities of the coronavirus.

Starnes wrote in hers that the pandemic was “an emotional roller coaster” but it taught the women she is locked away with to stick together, like family.

“It taught us unity and selflessness,” Starnes wrote. “So to the hands that receive this letter, know you’re not alone.”

She recommended her reader take time to help other people. She suggested making something for a neighbor, telling someone good morning, and she said, “Remember, you’re beautiful! Everyday is a great day. Even the bad days make us stronger!”

Asked about her letter, Starnes said she “finds comfort in comforting people.”

Courtesy Poetic Justice and Se'Nae Starnes

Se’Nae Starnes’ letter offers simple advice on making it through the pandemic a day at a time.

Getting these letters into their readers’ hands wasn’t straightforward. The participants had to work around the strict security employed in prisons without meeting face to face.

The correspondence class is made up of women inside Mabel Bassett and Eddie Warrior Correctional Centers, and their writing partners outside of prison.

The women and their partners sent messages to each other and then they passed the letters they received on to someone else.

“So it’s written to somebody you don’t even know. You don’t even know who is going to get it,” Kate Forest, board vice president of the nonprofit writing project Poetic Justice explained.

In addition to sitting on Poetic Justice’s board, Forest is a part-time staff member. The Oklahoma-based organization created the correspondence course in which Starnes wrote her letter. During normal times, Poetic Justice offers in-person restorative writing and creative arts programs to incarcerated women. The pandemic forced them to adapt.

Forest says it’s hard for people in state prisons to have fluid communication with the outside world even in the best of times. They can’t receive phone calls. They can get emails but they can’t send an email back.

If they try to call someone and the person doesn’t pick up, they may have to wait hours before they can try again. Forest says often when someone in prison wants to communicate with people outside, the prisoner has to reach out.

“I think a lot of what we wanted to do was simulate people reaching out to them as much as possible,” Forest said. “How can we get companionship to them with all the restrictions and barriers that are in place?”

Poetic Justice’s leaders and Department of Corrections staff hoped these letters would remind the women that their thoughts and feelings are still valuable to people outside of prison.

“I think one of the benefits is … processing through the shared sense of isolation, it’s reminding us that we all went through this pandemic and we’re still going through it,” Forest said.

Starnes says these letters and the rest of the correspondence course have been a bright spot in a very hard year.

One woman wrote that the past year was the hardest of her life. Nearly every woman inside Eddie Warrior caught COVID-19 last fall.

Starnes says a few women didn’t show symptoms at all.

“But the majority of us felt like we were on our deathbed,” she said. “When one of us was feeling good that day, we had to look out for the other ones and vice versa.”

People Starnes knew – people she calls her prison family – died. Other women lost actual family members to COVID-19.

They mourned inside packed dorms and outside when they got the chance.

Starnes expects to be released on parole soon and she says when she gets out she wants to work with a program like Poetic Justice to help the women who won’t be leaving with her.

When in prison, Starnes says hearing your name at mail call means a lot.

“Being encouraged by things like that, you’re less likely to fall back into what you were into before,” she said. “You have people that love you around you and that keeps you going.”