Stilwell High School teacher and local author Faith Phillips.

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Stilwell High School teacher and local author Faith Phillips.

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Faith Phillips is a great teacher.

In only two years teaching English and creative writing at Stilwell High School she’s got a few accomplishments under her belt:

She helped her students put together a podcast that was a finalist in NPR’s student podcast challenge. She wrote a grant for new exercise equipment at the middle school gym. She even led a crowdfunding campaign to buy laptops for students to use in class.

The 42-year-old is hanging it up after a difficult time. She never really wanted to teach more than one year, but she felt like she couldn’t leave the classroom in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Now she’s leaving the profession, which she said is the most difficult job she’s ever had.

“When you have 120 souls that are leaning on you and need your ear, and they want to tell you their problems, when you get home at the end of the day, you’ve got nothing left for anybody, not even yourself,” she said.

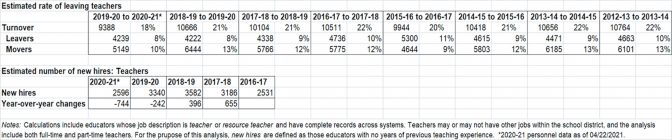

Thousands of Oklahoma teachers make a similar decision every year. Annually, more than 4,000 of Oklahoma’s roughly 45,000 teachers leave the profession in the state and the number of new hires is consistently lower.

And at Stilwell, the job is just plain hard. More than 90% of the school’s students are economically disadvantaged and nearly ⅔ are below target for academic achievement on the state’s school report card. That means there’s lots of trauma in the school, Phillips said.

“You’re expected to wear so many hats. You’re a counselor, your family member if you do it right,” Phillips said. “Especially with the students that I work with, if you do it right, you’re a family, you’re a support for people who don’t have support… it’s draining.”

Oklahoma State Department of Education

Joy Hofmeister, State Superintendent of Education

The teacher shortage isn’t a new problem. In the most recent school year, Oklahoma had 2,785 emergency teachers – teachers who aren’t fully qualified but allowed to teach if there’s a need. Ten years ago, there were less than 100.

“We’re just not retaining teachers,” said Robin Fuxa, Director of the Professional Education program at Oklahoma State University.

Fuxa is in charge of a program at OSU that trains new teachers in college. That program and others like it around the state can’t keep up with the turnover that Oklahoma schools see annually.

Many of the problems come down to money, she said.

Low pay and high stress are consistently cited as a reason for leaving. A 2018 survey – conducted before Oklahoma’s teacher walkout – cited those two factors as the top reasons teachers quit.

And the resulting shortage has been the most important issue of concern for Oklahoma’s highest education official – state schools superintendent Joy Hofmeister.

“You can have high standards,” she said, “you can have great facilities, but if you don’t have the teachers to teach, what good is it?”

The state has laid out a number of initiatives since 2015 when Hofmeister took office.

That includes a raise in 2018 around the time of the teacher walkout, a decrease in mandates from the state of what should or shouldn’t be done in the classroom and additional supports to dealing with student trauma.

And Hofmeister is cautiously optimistic that the measures are having an impact across the state.

In fact, the 2020-21 school year teacher turnover rate – the numbers of teachers leaving or moving districts – was the lowest it’s been since at least 2013, according to Oklahoma’s State Department of Education.

Nationally, a mass exodus of teachers due to the pandemic never really materialized. Economists think that’s because of a desire to keep a stable job during the unpredictable COVID-19 pandemic.

Regardless, the number of teachers leaving the profession had been steadily decreasing after the walkout in 2018, according to state numbers. Additionally, teacher pay is rising in comparison to the state’s neighbors.

“We have made improvements and I don’t want that lost in the recognition that, yes, we are not out of the woods and no, we have not yet achieved what our kids deserve,” she said. “But we will keep our eyes on what is most important for students. And that is a great, well-rounded education. And it starts with great teachers.”

Despite the progress made, Oklahoma is facing another problem, Fuxa said.

A so-called “retirement cliff” is approaching. Teachers’ pensions are determined by their last three years on the job so many might be looking to retire after completing their third year of school after the 2018 raises, Fuxa said.

“We have a lot of boomers who are retiring,” she said.

The key to replacing those teachers, Fuxa said, will be getting more who are traditionally certified into the classroom. Emergency and alternative certified teachers are less likely to stay in the field.

Fuxa said state leaders need to look at incentivizing Oklahoma teachers’ college graduates to stay in the state. Districts from other states are regular attendees at OSU’s teacher job fairs, she said.

Hofmeister said a sudden, massive influx of federal dollars will help with stabilizing the workforce.

“The federal relief funds are coming at just precisely the right moment,” she said.

Teacher turnover happens in districts that are the most poorly funded, Hofmeister said. So the state is looking at ways to better leverage the billions of federal dollars to retain and recruit qualified teachers, she said.

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

This sign proclaiming Stilwell as the “Strawberry Capital of the World” greets visitors as they come into town.

For Phillips in Stilwell the job was worth it.

Sure, it was hard. Easily the hardest job she’s ever had and she previously worked as a corporate lawyer.

While she’s writing, she doesn’t want to completely lose contact. Phillips said she plans to stay involved in the arts in Stilwell.

Working with the youth in her old town was inspiring too. Helping them develop podcasts and tell the story of their community was tremendous.

“It makes me sad,” she said. “It does. And I know that I’m going to be missing out on a lot.”