A sign is seen outside of 50 Penn Place in Oklahoma City where Epic Charter Schools leases 40,000 square feet for administrative use.

Whitney Bryen/Oklahoma Watch

A sign is seen outside of 50 Penn Place in Oklahoma City where Epic Charter Schools leases 40,000 square feet for administrative use.

Whitney Bryen/Oklahoma Watch

Courtesy Christina Glenn

Christina and Brendan Glenn. Brendan is a senior student at Epic Virtual Charter Schools and his mom says despite negative headlines, the school has helped him academically.

Christina Glenn knows her son’s success is due to Epic Virtual Charter Schools.

Brendan Glenn had been struggling in high school before transferring to Epic halfway through 9th grade. And now, the senior is on track to graduate.

“They’ve done a fantastic job,” Christina Glenn said in a telephone interview from her Stillwater home. “And they’ve helped him become successful. Working his own pace, his grades have gone from barely making it to he’s now making all As and Bs.”

Epic has been in the headlines for all the wrong reasons in recent days following the release of a state audit report:

But this leaves families like the Glenns puzzled.

Their main conduit to the school is Pat Walker, Brendan’s Bartlesville-based teacher. And she’s tremendously helpful, answering emails and texts at almost any hour and offering in person tutoring time in Bartlesville, where the Glenns lived when Brendan started at Epic.

So, they’re just pressing on.

John Harrington, the chairman of the Statewide Virtual Charter School Board says families like the Glenns are doing exactly what they need to do.

“Despite this present difficulty, your school is still in session, your homework assignments are still due and your tests still need to be graded,” Harrington said Tuesday while addressing Epic families and teachers. “That is not changing today.”

And it’s unlikely to change this school year. Because of the length of the termination process, Epic will have multiple chances to defend itself over the coming months, it won’t close its doors in the middle of the spring 2021 semester either.

But changes are coming. Epic proponents say they’re the result of a politically motivated witch hunt while opponents say it’s change that’s long overdue.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact

An Epic advertisement at an Oklahoma City mall. The school has been criticized for its aggressive advertising campaigns.

Turmoil has swirled around the school for years.

The virtual charter’s first sponsor, the University of Central Oklahoma pulled out and eventually paid a $60,000 settlement to end its association with the school in 2011. The district sued the State Department of Education for not releasing its school district report card at the same time as others in 2013. And it’s been the subject of an Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation criminal probe starting in 2013 that included a warrant filed last year alleging its founders pocketed $10 million in state funds.

The controversy has drawn in critics from every level of state government and in 2019, Gov. Kevin Stitt called on State Auditor Cindy Byrd to perform an investigative audit on the district.

The audit alleges a laundry list of violations.

“I have seen a lot of fraud in my 23 years,” Byrd said. “And this situation is deeply concerning.”

Her report said Epic was given almost half a billion dollars over the last five years. And of that, at least $125 million has been siphoned through a learning fund that goes to families and a for-profit management company operated by Epic’s founders Ben Harris and David Chaney.

Because there’s no oversight of that money, it’s unknown if that money actually went toward educating kids, Byrd said. And that’s a big problem.

Those records remain tied up in litigation as Epic says they should remain private. But Byrd continues to fight for a full accounting of those dollars in court.

The audit report concludes that Oklahoma should consider that for-profit organizations running charter schools might not be a good idea.

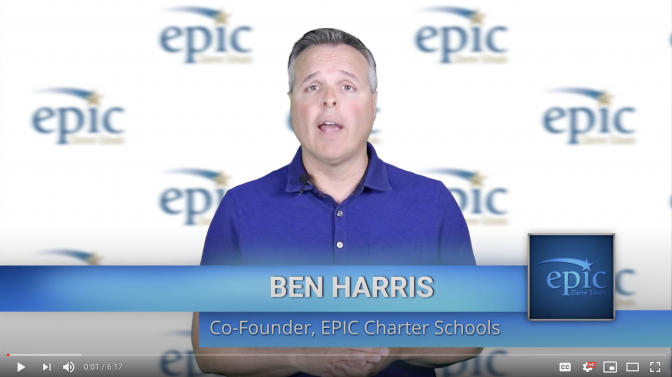

Screen capture, Epic Virtual Charter School video

Ben Harris touted Epic Virtual Charter Schools in a 2020 promotional video.

Epic Virtual Charter Schools is the largest school district in the state with more than 60,000 students – almost double Oklahoma City and Tulsa Public Schools combined.

Much of that surge has been generated by an influx of students who wanted to move to a distance learning option because of the coronavirus pandemic. In a July video, co-founder Ben Harris touted the school’s ability to educate kids, even under intense scrutiny from outside forces. And he said that’s why families were flocking in despite headlines garnered by the school.

“Some of those families coming to us may be skeptical of sending their children to us because of the negative and unfair and often flatout inaccurate news about us the past few years,” Harris said.

Epic was already on pace to outgrow other school districts. It had consistently been increasing in popularity and size for years.

The growth had to do with aggressive advertising campaigns that have been scrutinized over they years and the district’s learning fund. Epic characterizes the learning fund as a way for parents to pay for $1,000 worth of educational materials. Critics call it a bribe.

The money in the learning fund has been the subject of legal battles. During her audit, Byrd tried to access the fund, which has received $80 million in public money over the last five years. However, Epic blocked auditors from analyzing it, contending that it was disbursed by their private management company Epic Youth Services. There is a court case about whether the auditor’s office should have access to the funds scheduled for December.

The fight over the fund feels far removed from the virtual classroom, though.

“It’s school as usual for us,” Amanda Cole, an Epic parent who manages an Epic family Facebook page, wrote in a message to StateImpact. “This is a long process that I don’t foresee affecting the current school year.”

Cole’s children have been enrolled in the school for years. And she said she trusts its leaders.

In the promotional video, Harris said the district would prove itself using its educational model while facing down the pandemic.

“I’m glad we are here to make sure they don’t have to choose between a school they don’t think is safe for their child and their child having a quality education,” he said. “No parent should have to make that choice.”

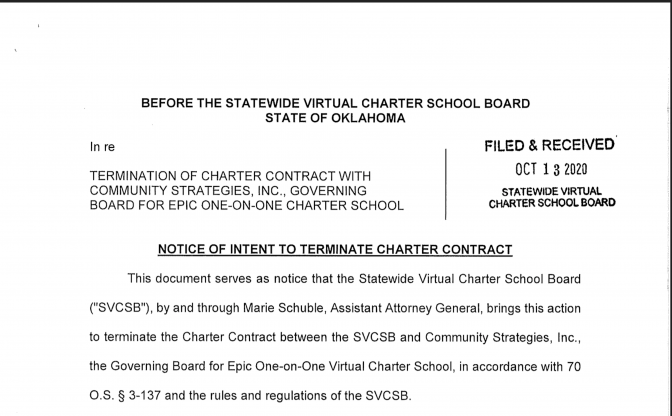

A copy of the notice of intent to terminate Epic Virtual Charter School’s Contract with its state authorizer.

There will likely be a long, protracted battle over the future of the massive school. Millions of dollars are at stake as well as the lives of 60,000 Oklahoma school children.

The next significant event will be a January trial of sorts before the Statewide Virtual Charter School Board.

At that hearing, Epic will have a chance to defend itself against the allegations made in a 30-page intent to terminate document prepared by Assistant Attorney General Marie Schuble.

Schuble’s argument will be that Epic broke state laws, handled money inappropriately and didn’t cooperate with the state audit.

If the contract is subsequently terminated, Epic will have a chance to appeal to the State Board of Education.

If the state education board upholds the termination, there’s then another lengthy closing process that could take months.

Additionally, Epic is actually two schools and this contract only impacts the one-to-one model of virtual education. The charter for blended schools in Oklahoma City and Tulsa is actually managed by Rose State College. And that college has given no indication of what it might do should Epic’s virtual contract be terminated.

But all of this is far removed from the day-to-day life of Epic families. Christina Glenn said her son Brendan was a little worried about it until they had a conversation about the actual implications it would have on him. He’s a senior, and because of that process it’s practically impossible for the school to close before he graduates.

So for the short term, the Glenn family isn’t worried. Going forward, and for different people, though it’s a different story.

“There’s hundreds of other Brendans in this world,” Christina Glenn said. “What’s going to happen to them?”

Regardless of what’s occurred, Epic’s model needs to be available for struggling students, she said. They don’t deserve the same level of criticism as the folks who’ve put Epic in the news.

“If someone higher up did something bad, the teachers didn’t do it, the students didn’t do it,” she said. “I don’t feel like everything should suffer. I’m very passionate about this because it turned around a lot of things for my child.”

This COVID-19/education reporting is made possible through a grant from the Walton Family Foundation.