Shawnee Superintendent April Grace.

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Shawnee Superintendent April Grace.

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Shawnee Public Schools custodian Lavonne Harris wipes down a door knob at the district’s central office.

Lysol is Lavonne Harris’ most powerful weapon against pandemic.

The custodian for Shawnee Public Schools is wielding the disinfectant inside her district’s school board room to fight off the novel coronavirus that’s infected hundreds of thousands worldwide.

This stuff will “kill all the germs,” she says.

Across the state, people like Harris are taking similar actions to sanitize areas where large groups of people congregate daily in public.

StateImpact reporters checked in with leaders of schools and jails to see how they’re preparing for a pandemic.

School districts are prepped for the virus to spread and will be closed for at least three weeks after an order from the state. But district leaders are concerned about finding ways to feed and educate students moving forward.

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Shawnee Superintendent April Grace.

Shawnee Schools Superintendent April Grace said she is most concerned about exhibiting leadership in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The number of confirmed cases in Oklahoma ticks up daily, and with it, general anxiety does too. That means decisive leadership is necessary.

“I think our job as leaders is always to handle things as effectively, and efficiently and as calmly as possible, try to put people at ease and always try to consider that larger scope of what our responsibility is to kids,” Grace said.

Grace applauded the move by State Superintendent Joy Hofmeister and the State Board of Education to close schools for three weeks. But it does leave superintendents like her scrambling to provide services to kids.

A vast majority of the 3,800 students in Shawnee receive free or reduced lunch, and Grace said it’s critical they continue to get meals daily.

The district will take similar action to what it did during the 2018 teacher walkout that closed schools for weeks. Buses will deliver food to students along their normal routes, Grace said.

“In some cases that may mean meeting them at either the doorway, or the porch or driveways,” she said.

But more urban districts want to feed their children, too. Oklahoma City Public Schools Superintendent Sean McDaniel said that was one of his chief concerns during a school board meeting Tuesday.

“We want to feed two meals a day as long as we’re out,” he said.

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Oklahoma City Public Schools Superintendent Sean McDaniel at a January press conference.

In Oklahoma City, going door-to-door would be impractical. However, the district is exploring ways to centralize grab-and-go options for students to get food.

Another concern is for the well-being of hourly employees. Teachers and administrators will be paid throughout the closure. But other employees who miss work for extended periods won’t likely get as many hours as when school is in session.

McDaniel said the district is exploring ways to get them work and to perhaps get some paid leave as well.

Once those issues are figured out, a big hurdle remains for superintendents across the state.

And that won’t be solved easily: how can students continue to learn in the face of massive, long-term closures.

“We’ll have to revisit what does instruction look like? How do we take care of our most vulnerable kids?” McDaniel said.

So far, advocates for Oklahoma sheriffs say they haven’t heard of any coronavirus cases inside county jails.

However, jails are perfect places for a contagious virus to spread.

Oklahoma County Sheriff P.D. Taylor told county commissioners this week the jail has to run 24 hours a day and it can’t be shut down.

That means the jail’s staff and its prisoners have no choice except to stay and keep the virus outside.

Captain Gene Bradley, helps run the jail for the sheriff’s office. He says a person who could be infected with coronavirus would be isolated inside one of seven negative airflow cells in the jail. These cells are designed similarly to some rooms found in hospitals.

Air that enters the cell is vented outside of the building instead of being allowed to circulate through the rest of the jail.

“Fortunately, with (the) renovation of the jail and the lower population, we’ve got two pods that are available to do large scale isolation as well,” Bradley told Oklahoma County Commissioners.

Oklahoma County and around half of other county sheriffs in the state have contracts with a company that provides medical care for prisoners. The rest will rely on medical professionals in their communities to help them through the pandemic.

Multiple sheriffs say their jail staff will be screening new prisoners for symptoms of coronavirus. If someone shows symptoms they could be sent to a hospital or put into isolation. New prisoners will also be asked a list of questions such as whether they’ve travelled outside of the United States recently.

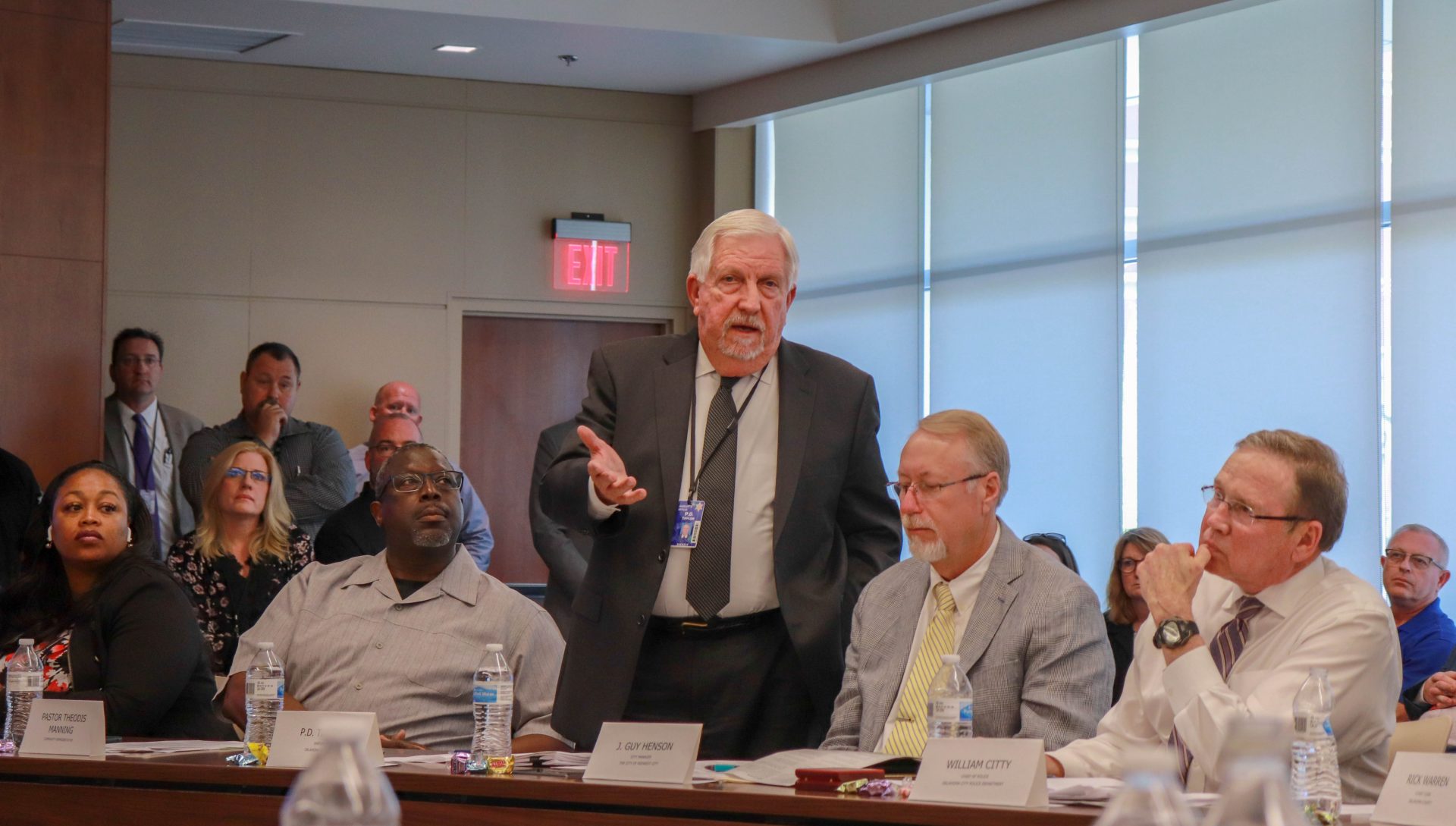

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Oklahoma County Sheriff P.D. Taylor says his jail must operate for 24 hours a day and telecommuting is not an option for many of his staff.

News 9 reported two years ago that Oklahoma County had to shut off the water to its jail in order to make badly needed repairs.

In the same year, the station reported prisoners clogged their toilets so that raw sewage flooded the basement of the jail, near the kitchen – it wasn’t the first time.

Old flawed buildings and the maintenance problems that come with them are a familiar headache for jail administrators, but lack of water or bad plumbing could be a serious weakness in efforts to stave off coronavirus.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Oklahoma State Department of Health, American Correctional Association and other organizations offering advice on preventing a viral epidemic in Oklahoma’s jails all say keeping the buildings clean is extremely important.

Some of the most simple and effective measures large populations can take to stop the virus are regular hand washing and cleaning heavily used surfaces often.

Sheriffs around the state say they can only keep prisoners’ living areas as clean as the prisoners are willing to make them.

Many jails also prohibit prisoners from having alcohol-based hand sanitizers. Jail supervisors fear prisoners would abuse the alcohol.

Ray McNair, executive director of the Oklahoma Sheriff’s Association says it’s also harder for smaller counties to quarantine prisoners.

He says to keep sick people in their own cell, some counties may have to resort to “double celling or possibly even triple celling (prisoners).”

McNair says sheriffs and their deputies are also having trouble finding protective equipment like masks and gloves. The supplies they need to wipe down surfaces as suggested are also harder to come by.

Public defenders and other prisoner advocates are calling for jails to open their doors and release low level offenders during the pandemic. Oklahoma County officials are considering doing it and so is Tulsa County.

Steve Kunzweiler, Tulsa County’s district attorney, says he’s hopeful his prosecutors and public defenders can negotiate resolutions to multiple cases.

He’s focused on cases that would typically end with the defendant serving a probation term, being released for time served or some combination of the two.

Multiple criminal justice stakeholders want fewer people in jails while the pandemic plays out.