Pardon and Parole Board members have drastically increased the number of recommendations for commutations and paroles in the last year.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Pardon and Parole Board members have drastically increased the number of recommendations for commutations and paroles in the last year.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Pardon and Parole Board members have drastically increased the number of recommendations for commutations and paroles in the last year.

Emotions run high with anticipation inside the meeting room where the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board regularly decides the futures of hundreds of state prisoners.

A webcam beams the image of a woman wearing prison coveralls to a monitor at the monthly pardon and parole meeting. She sounds hopeful as she and her brother discuss her case with board members.

Her brother says she deserves a second chance.

“I can’t stress enough, she’s not the same sister she was four years ago,” he said.

The brother told board members his sister was now a full-time college student and was only five credits away from graduating with an associates degree.

The board voted to recommend Gov. Kevin Stitt give the woman a shorter sentence. If the governor agrees, she could also get an earlier parole consideration.

Pardon and Parole Board member Allen McCall says that’s what the board really wants.

“What we want to do is get her back in front of us,” McCall said. “If she keeps doing as well as she’s been doing, maybe give her parole with some conditions to follow so that she has some structure.”

Most of the board’s members are new appointees who joined in 2019. Inside of a year they’ve drastically increased the number of recommended commutations by 2,699 people. They increased parole recommendations by 925 people.

The board approved 635 of those people for administrative parole which is a faster process created by a 2018 reform law.

Not all of those people got parole. Some finished their sentences before the paperwork went through and were released without supervisory conditions, and some were held back as punishment for prison misconduct. Some of the people who weren’t on the administrative parole list also had to get approval from the governor.

The work of the Pardon and Parole Board, combined with a series of reforms that led to the largest commutation in U.S. history last year has helped Oklahoma shed its status as the state with the highest imprisonment rate in the nation.

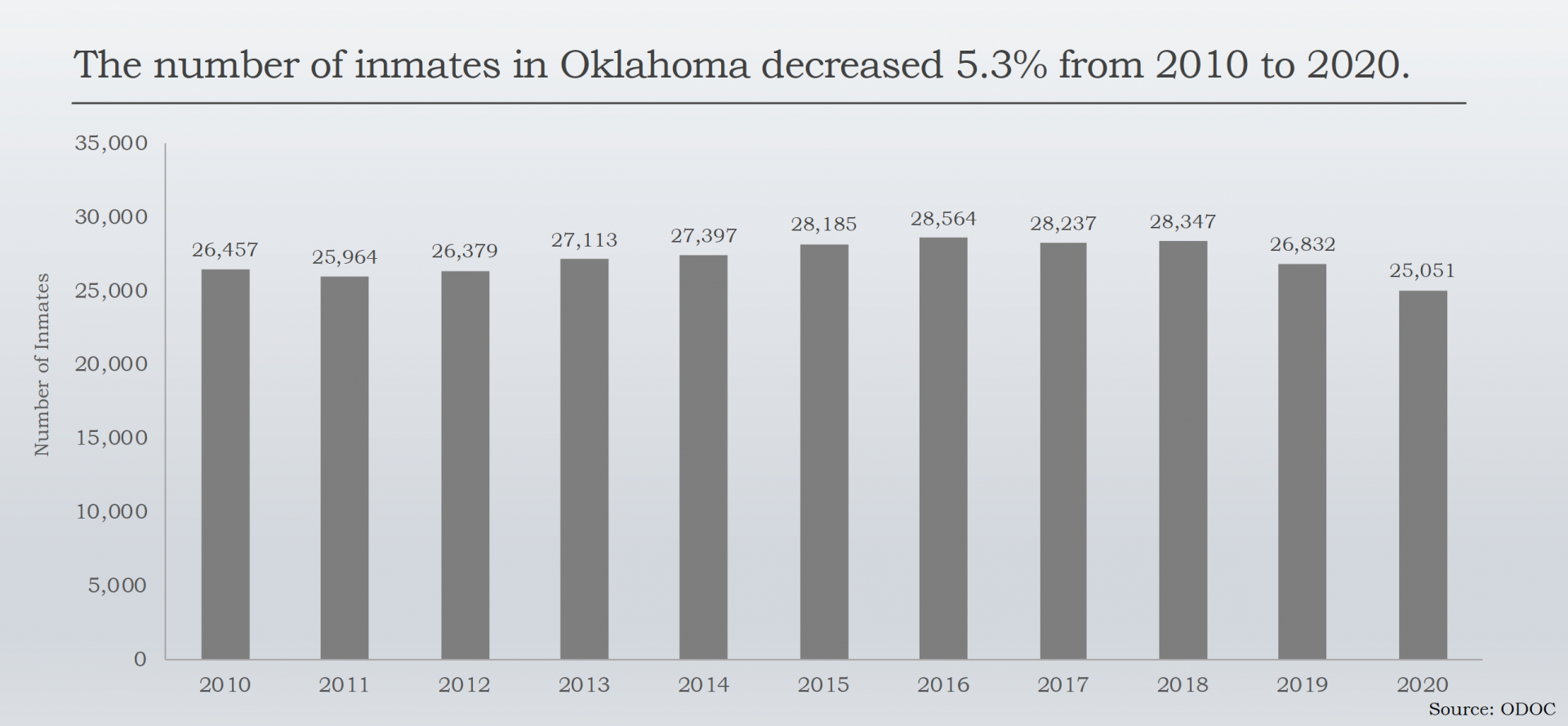

Gov. Stitt, legislators and other state leaders cheered the progress. The state has almost eliminated its system-wide overcrowding, and state Department of Corrections data presented at a forum in January suggests the prison population is at its lowest point in 10 years.

But, criminal justice expert Len Engel a policy director with the Boston-based Crime and Justice Institute, warns that these gains are temporary.

Engel and his team were invited to Oklahoma after Gov. Mary Fallin and lawmakers requested federal assistance. The federal government paid the consultants to give lawmakers advice on how to fix Oklahoma’s prison population crisis. When Engel came to the state in 2016, state leaders feared prison overcrowding would lead to a disaster.

Prisons were more than 110% over capacity, and the population was growing.

Oklahoma Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs / StateImpact Oklahoma

This graph was presented during a public safety forum hosted by the Department of Corrections.

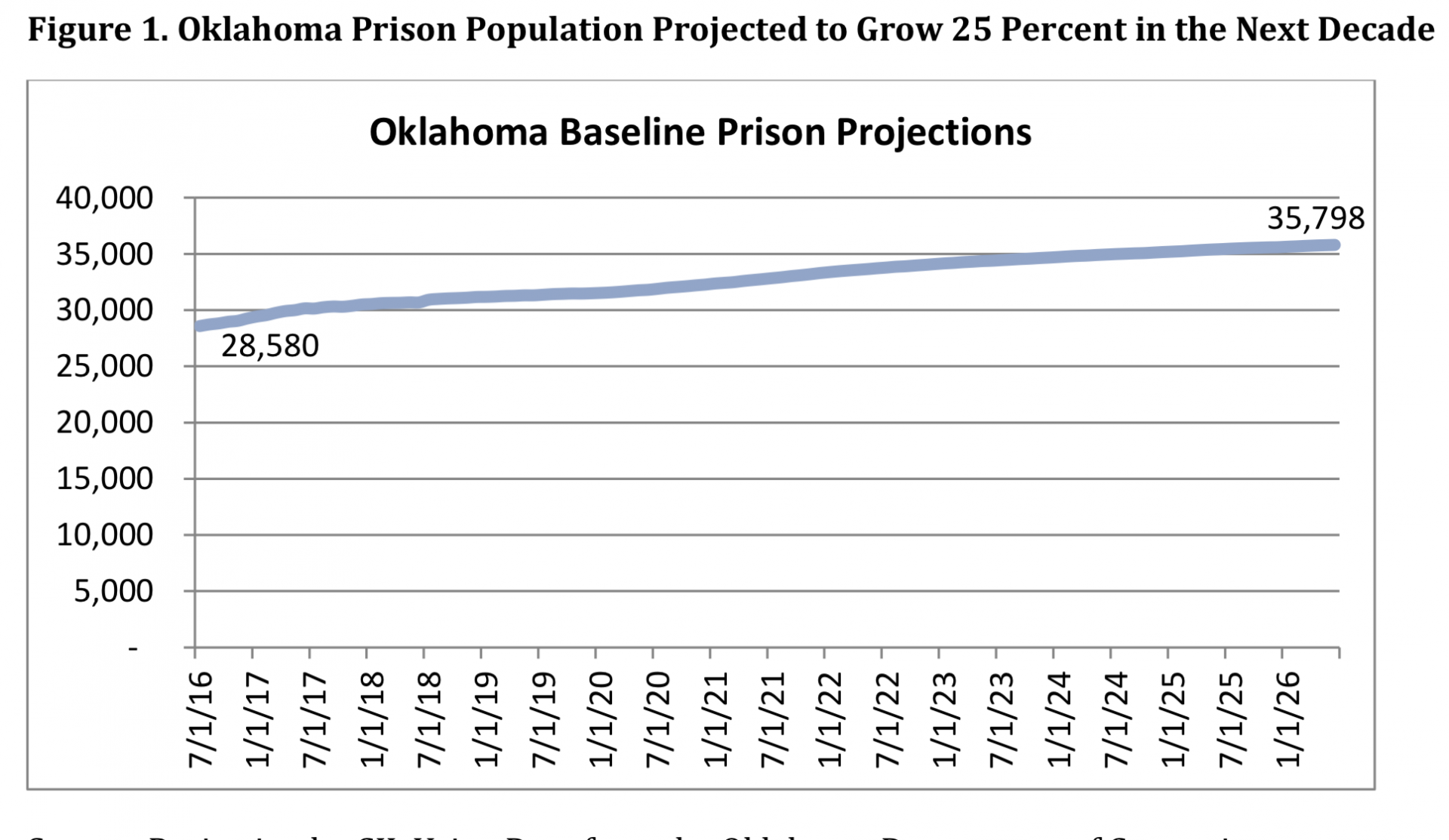

Engel says Oklahoma is in a better place than it was years ago, but the state deferred criminal justice reforms other states were adopting for so long that recent actions have only slowed its prison population growth.

“You’ve addressed the immediate urgency of overcrowding, but you haven’t addressed the projected growth, which is going to continue and lead to more overcrowding unless more policy changes for the long term are adopted,” Engel said.

Engel’s team projected with no changes, the population would grow by more than 7,218 people between 2016 and 2026. He says reforms passed under Fallin and Stitt have helped, but people are still receiving long prison sentences.

Engel doesn’t know how much recent reforms have reduced the state’s projected growth.

Other policy experts are calculating new projections now. However, he and other reform advocates are asking: Will the Oklahoma Legislature enact policy reforms that change future growth rates?

Oklahoma Justice Reform Task Force / StateImpact Oklahoma

This trend line shows how much Engel’s team predicted the state’s prison population would grow by 2026. The graph was included in a 2017 report prepared for the Legislature by a task force formed by former Governor Mary Fallin.

House Majority Leader Jon Echols cosponsored the legislation that led to the state’s mass commutation last year. This legislative session, he wants to tackle recidivism – the percentage of people released from prison who are rearrested.

“How do we give drivers’ licenses to individuals? How do we give more access to services,” Echols asked.

He says if the state invests more in people leaving prison, it can mitigate predictions that nearly 25% of former prisoners will go back behind bars. A task force created by Gov. Stitt has also highlighted recidivism as a key challenge.

Echols and Senate Democrats also want to replace criminal fines and fees sent into state agencies’ budgets with state appropriations. Advocates say heavy fines and fees make it harder for people to start a law abiding life after prison.

But, Len Engel says that’s not enough. He says reducing recidivism is important but it won’t stop the state’s long term growth.

“I don’t see how it can be done without new policies focusing on people that are coming in the door and the amount of time that they’re spending,” Engel said. “You’ve got to do both things.”

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

House Majority Leader Jon Echols (second from right) listens to the Pardon and Parole Board Meeting where more than 450 state prisoners sentences were commuted at once.

A small number of lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have proposed bail and sentencing reforms including eliminating mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent crimes.

Echols says he’s not opposed to sentencing reform, but he believes the wide range of opinions in the Legislature will block those efforts.

“We (have to) engage in the art of the possible,” Echols said. “We had a huge deal last year with the retroactivity bill. I don’t know that we’re going to have that level every year. I think that’s unrealistic.”

The retroactivity bill Echols referenced is responsible for the 2018 sentence commutations for more than 450 prisoners. There were other bills addressing sentencing that initially got strong support but languished when the House and Senate deadlocked.

Len Engel says higher level sentencing reforms are often hard sells in state Legislatures, but other states made the changes when they decided they wanted to spend more money treating addiction and other problems driving crime, instead of paying for more prison beds.

Oklahoma lawmakers are considering more than two dozen bills this year addressing prison overcrowding and criminal justice reform.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this story said Len Engel was hired by former Gov. Mary Fallin. Engel and his team were invited to Oklahoma after Fallin and lawmakers requested federal assistance. The team’s work was funded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance through the Justice Reinvestment Initiative. Engel’s name was also misspelled.