Sixth grade science teacher Melissa Lau prepares a lesson on climate change using "tree cookies" for her students at Piedmont Intermediate on July 1, 2019.

Sixth grade science teacher Melissa Lau prepares a lesson on climate change using "tree cookies" for her students at Piedmont Intermediate on July 1, 2019.

Melissa Lau is preparing for the coming school year. She teaches 6th grade science in Piedmont, just northwest of Oklahoma City. Inside her classroom, she’s laid out over thirty cross sections from the trunks of red cedar trees. Each ring represents one year of growth. Lau calls them “tree cookies.”

“Once I get them cleaned up a little bit more they’re going to show students a historical record of that dry years are getting drier and our wet years are getting wetter,” Lau said.

The trees grew near a Mesonet station in Guthrie. Lau wants her students to match the varying tree rings to the station’s rainfall data from the past 25 years.

“This is a very concrete representation of the abstract data and numbers,” Lau explained.

Extreme weather patterns are projected to intensify in Oklahoma due to changes in the climate caused by rising carbon emissions. According to the latest National Climate Assessment, alternating flooding and drought events have already increased over the last 50 years.

Lau says she has been educating her students about the connection between fossil fuel combustion and climate change for three years, though she isn’t required to. Oklahoma’s K-12 science standards are based in part on the Next Generation Science Standards, national guidelines developed in 2013 that recommend teaching the concept in sixth grade, but Oklahoma left it out.

Oklahoma’s standards do include language on weather patterns, changes in the environment and variations in regional climate conditions, as well as human activity and its effect on the planet. However, teaching about how fossil fuel combustion relates to these broad categories remains optional.

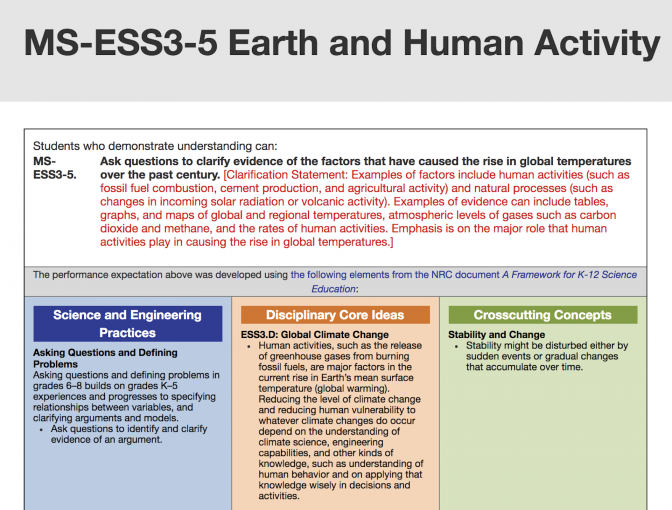

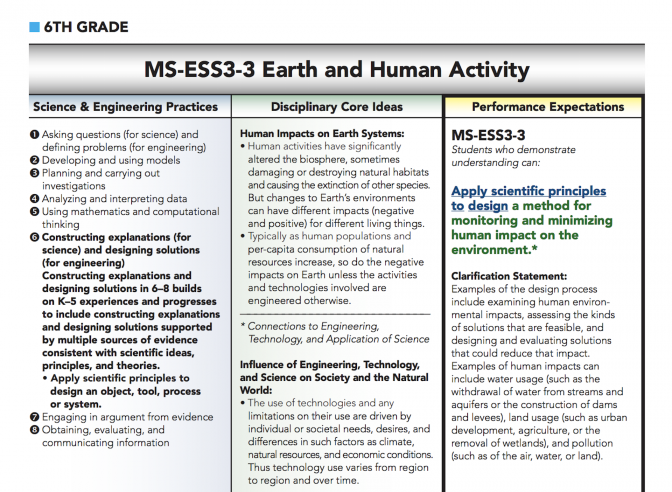

The Next Generation Science Standards include a section on “Earth and Human Activity” for sixth graders that explicitly addresses “the major role that human activities play in causing the rise in global temperatures.”

Oklahoma’s 6th grade “Earth and Human Activity” standard differs significantly from the NGSS equivalent (pictured above). It does not mention fossil fuels, rising global temperatures or climate change.

Past Resistance

Every six years the education department assembles a group of educators from across the state to review and revise state science standards, but state lawmakers have the final say over these education guidelines.

Even without the explicit connection between industrial carbon emissions and rising temperatures, some lawmakers still had misgivings about today’s standards when they went before the state legislature in 2014.

“There’s been a lot of recent criticisms in some sectors as to what some consider hyperbole relative to climate change,” remarked former Republican state representative Mark McCullough in a committee hearing on May 12, 2014.

McCoullough was questioning Tiffany Neill. At the time, she was the director of science education for Oklahoma.

“Do you believe that the sections section specifically relating to weather and climate, particularly at the at the earlier ages, as it’s emphasized here in the new standards could potentially be utilized to inculcate into some pretty young impressionable minds a fairly one sided view as to that controversial subject?” McCoullough asked Neill.

McCoullough wasn’t the only lawmaker who pushed back. There was support in both legislative chambers for two separate resolutions rejecting the standards, though they ultimately failed.

A recent NPR survey showed sixty-six percent of parents believe should teach kids about climate change and its impacts, but among Republicans that number drops to just 49 percent. In a red state like Oklahoma, that division could lead to a political battle as the State Department of Education reconsiders what public school students should learn as part of their science education.

The Next Round

Neill is now the Executive Director of Curriculum and Instruction, and she’s facilitating the current round of science standard revisions. She says teachers are free to teach about fossil fuels and climate change if they want to.

“Every teacher is able to utilize the existing standards to make determinations about teaching anything related to climate that they so choose, and that is really, I believe, where we want the authority for much of the curriculum decisions to lie,” Neill said. “The Oklahoma standards focus on a breadth of ways in which climate is changing, and looking at the variety of mechanisms that may be causing that.”

Lau, the teacher from Piedmont, uses the current standards to teach about human-caused climate change, but she says she knows many science teachers who’d rather not broach the subject. The NPR survey supports her claim. Polling showed less than half of teachers in the United States discuss climate change in the classroom.

“I’m lucky where I am in Piedmont. The community and administration is extremely supportive, but I know that there are other science teachers in the state that avoid it for the reasons of just not wanting to have to deal with the drama,” Lau said.

Lau is one of the educators selected to participate in the revision process. She believes adding more explicit language around fossil fuels and climate change would give science teachers something to fall back on if they encounter resistance from parents or administrators. But she worries it would prompt a political backlash.

“Legislators may just see the term climate change and be like ‘I am against that. My party is against that. I don’t want to support that, so therefore, I’m not going to pass your science standards,’” Lau speculated. “The struggle is do we write our standards for somebody who is not scientifically literate or do we write them for science teachers?”

Twenty-six other states adopted the recommended national standards including language showing an explicit relationship between fossil fuels and the changing climate. Oklahoma’s revision process is just starting, and new science standards are expected to go before the legislature next spring.