An inmate uses a lathe to machine a trailer part at the Skills Center inside McCleod Correctional Center near Atoka, Okla..

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

An inmate uses a lathe to machine a trailer part at the Skills Center inside McCleod Correctional Center near Atoka, Okla..

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

An inmate uses a lathe to machine a trailer part at the Skills Center inside McCleod Correctional Center near Atoka, Okla..

Confinement is only part of the mission at Oklahoma prisons.

More than 25,000 people were incarcerated at state prisons last year, data from the Department of Corrections show. Most of those people will be released one day. Felons vow to never return. Officers and taxpayers — who are on the hook for $20,000 per inmate every year — hope they don’t.

One of the best ways to increase the odds, corrections officials and criminologists say: Help felons find jobs.

Researchers have identified a litany of risk factors when it comes to criminal behavior and recidivism. Felons in Oklahoma often come from poverty, are poorly educated and enter prison saddled with addictions, mental health and severe behavioral issues.

Many simply can’t read, says Clint Castleberry, programs administrator for the state Department of Corrections. And while treatment and teaching might not seem “tough on crime,” it helps make offenders more employable.

Ex-offender jobs issues affect all Oklahomans. Here’s why and how:

Source: U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics / Via: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation

Oklahoma ranks No. 3 in prisoners per-capita. Click here to see a state-by-state breakdown.

There are about 654 prisoners per 100,000 Oklahomans, data from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics show.

That means Oklahoma is No. 3 when it comes to state incarceration, trailing Mississippi and Louisiana.

Roughly one in 12 Oklahomans has a felony conviction, according to the DOJ. But state corrections data show that number could be as high as one in eight, says Justin Jones, director of the Oklahoma Department of Corrections.

Employment increases an offender’s odds of staying out of prison once he or she is released, state corrections officials say.

“You need to find meaningful employment, you need to stay busy,” Jones says.

National research confirms this.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

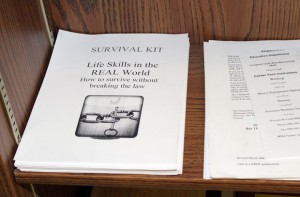

Job training at the Skills Center at the McLeod Correctional Center starts with the basics.

Employment has a side benefit of reducing other recidivism risk factors. A 2009 study on Pennsylvania’s parole system by the Center for Criminal Justice Research at the University of Cincinnati (click here to download) examined a program that required offenders, as a condition of their parole, to find and maintain verifiable employment. This cut down on offenders interacting with other risk groups and increased the likelihood that those offenders wouldn’t return to prison.

Another 2009 study, published in the October 2010 International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, supports the claim that employment reduces recidivism. While employment doesn’t significantly reduce the likelihood of re-incarceration, it does significantly increase the amount of time an offender will spend beyond prison.

“… Those who obtain employment spend more time crime-free in the community before returning to prison,” researchers concluded.

Helping felons find jobs is a start, but giving them training for a career is even more effective, says Jim Meek, superintendent of the prison Skills Centers. A job “turning burgers” isn’t enough, he says.

“If we’re able to place them in a training-related position, there is a significant difference in their recidivism,” Meek says.

Oklahoma offenders who received career training had a 10 percent greater “survival rate” than their untrained prison peers, a 2009 study of state Skills Centers shows. That translated into 55 fewer felons returning to prison, according to the study, which used 2004 state prison data.

Oklahoma spends big on prisons. The Department of Corrections received more than $459 million last year — more than Oklahoma spends on courts, the Highway Patrol and all state police agencies combined.

Inmates receive education and some jobs training through the Department of Corrections. Selected inmates receive training — such as welding, equipment operating, machining and construction — at the Skills Centers.

Both have suffered from state budget cuts.

Skills Center training costs taxpayers about $3,260 per prisoner, records show, and the total cost of training the 545 offenders examined in the 2009 study was about $1.78 million. But giving offenders career training saved the state more than $3.3 million in inmate housing costs, the study shows.

Employed offenders are also taxpayers. After five years, those 55 prisoners collectively added more than $1.5 million to state tax coffers, the study shows.