Background

At least forty people have died from the West Nile virus in Texas as of early September. The neuroinvasive strain of the virus has been confirmed in nearly 500 cases in the state, more than any other year before. Naturally this brings up a lot of questions: Is it always fatal? Where in Texas is it a problem? How did it get here in the first place?

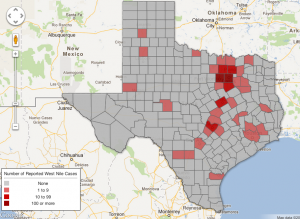

Where West Nile Has Hit Texas

Let’s start with where West Nile is in the state. As you can see in the map to the right by Texas Tribune, the virus is mostly in North and Central Texas. (Click here for an interactive version.) But new numbers reported by KUT News on September 6 show that the problem is becoming worse in Central Texas — mostly the area around Austin — while it’s improving in Dallas County, which has likely already hit its peak number of cases.

“If you look at Texas as a whole, the percentage of infected mosquitoes has gone down in the North Texas area but is staying up in the Central Texas area,” Texas Department of State Health Services (TDSHS) Commissioner Dr. David Lakey tells KUT News. “We’re still seeing about 28 percent of the mosquitoes that we test, as of earlier this week in Travis County, about 28 percent are still positive for the virus.”

Dallas has spent the past weeks spraying insecticide to kill mosquitoes, but there has been no aerial spraying in Central Texas. Travis County Health and Human Services says that the area can expect to see more West Nile cases, and that it’s everywhere in the county, not necessarily just in one place.

“There are mosquitoes carrying disease throughout Austin-Travis County,” Barasch says. “This is very pervasive and there’s not one particular spot that’s being hit harder than another. It’s out there, it’s everywhere, it’s here to stay in our community.”

What is West Nile Exactly, And Am I at Risk?

According to TDSHS, West Nile virus is an illness carried to humans by mosquitoes, “commonly found in Africa, West Asia, and the Middle East.” It first appeared in Uganada in 1937. “It is closely related to St. Louis encephalitis virus found in the United States,” TDSHS says. “The virus can infect humans, birds, mosquitoes, horses, and some other animals.” It first appeared in the U.S. during an outbreak in New York in August 1999, when several wild crows and exotic birds at the Bronx Zoo became ill with the virus and died. The virus may have come to the states in the first place from an infected mosquito or bird.

In most cases (up to 80 percent), those infected with West Nile will have no symptoms at all and simply recover without ever knowing they were sick.

But it’s the elderly and those with compromised immune systems who are in danger of having a potentially fatal reaction to the virus.

For the twenty percent that will show symptoms, they can experience either the milder West Nile illness or a more serious case of the virus. In the former, known as West Nile fever, “mild symptoms such as fever, headache, body aches, and occasionally a skin rash on the trunk of the body and swollen lymph glands,” according to TDSHS. This has infected over 500 Texans since the beginning of the year.

In the cases where there’s a “severe infection,” known as the neuroinvasive version of West Nile, the symptoms are much more serious. They include “headache, high fever, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, convulsions, muscle weakness, and paralysis,” according to TDSHS. “Only about one out of 150 people infected with West Nile virus will develop this more severe form of the disease.” But in Texas this year the numbers have been very high, with 495 people in the state confirmed to have West Nile nueroinvasive, of which 40 cases have been fatal.

Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

A mosquito control specialist releases skeeter-eating fish into a stagnant pool during a West Nile outbreak in California in 2009.

Overall, West Nile Fever and West Nile Nueroinvasive have shown up in over 1,000 cases across 82 counties in Texas this year. TDSHS says that the risk of getting West Nile is very low. “Even if the mosquito is infected, less than 1% of people who get bitten and become infected will get severely ill,” the agency says on its website. “The chances you will become severely ill from any one mosquito bite are extremely small.”

It takes three to fourteen days for the virus to incubate in humans, according to TDSHS. The milder symptoms last just a few days, but in the severe cases it can last several weeks and “neurological effects may be permanent.” TDSHS says it’s possible that once you’ve gotten the milder form of West Nile without even realizing it, you “would develop a natural immunity to future infection by the virus, and that this immunity would be lifelong.” But that immunity could go down in your later years.

Pets are at risk of West Nile, too, but TDSHS says that “the good news is they rarely, if ever, become sick from the virus.”

What Can I Do To Prevent Getting Bit?

Act the same you would if you were avoiding mosquitoes. The Texas Department of State Health Services recommends the following:

- Use bug spray with DEET, picaridin or oil of lemon eucalyptus.

- When outside, where long sleeves and long pants. (Easier said than done during a week of 100 degree-plus temps in Central Texas.)

- Don’t go outside at dusk and dawn, when mosquitoes are at their busiest.

- Get rid of standing water around your home, where mosquitoes breed. The agency says these spots can be anything from old tires to clogged gutters to flowerpots.

Is It Contagious?

West Nile Virus is primarily spread through a mosquito bite, but the Centers for Disease Control says that “in a very small number of cases, [West Nile] also has been spread through blood transfusions, organ transplants, breastfeeding and even during pregnancy from mother to baby.” But it isn’t spread through casual contact, like touching or kissing.

What Should I Do If I Think I’m Sick? Is There a Vaccine?

If you think you have symptoms of West Nile, you should see a doctor. The A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia says that West Nile is not treatable.

“The primary objective is to diagnose the patient as soon as possible so they receive the right medicines to treat the symptoms,” the encyclopedia says. “It is very important to lower fever and ease the pressure caused by swelling of the brain. Patients with very severe encephalitis are at risk for body-wide (systemic) complications including shock, low oxygen, low blood pressure, and low sodium levels.”

There is no vaccine for West Nile, but scientists are looking for one. The Centers for Disease Control says one could become available within a few years. While there is a vaccine for horses, the CDC recommends against using it in humans, because it hasn’t been studied and its effectiveness even on horses “has yet to be fully evaluated.”

Does This Have Anything to Do With Climate Change?

West Nile didn’t even exist in Texas until 2002, when the first death from the virus occurred. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), it didn’t show up in the U.S. until 1999. This year has seen the highest number of cases for the virus, in both Texas and the country as a whole.

The Scientific American looked into the question, and here’s what they found:

“Though the CDC doesn’t have an official response to that question, the director of the CDC’s Vector-Borne Infectious Disease Division said that ‘unusually warm weather’ may be to blame. So far, 2012 is the hottest year on record in the United States according to the National Climatic Data Center, with record-breaking temperatures and drought a national norm. It’s likely no coincidence that some of the states hit hardest by West Nile are also feeling the brunt of the heat. More than half of cases have been reported from Texas alone, where the scorching heat has left only 12% of the state drought-free. Fifteen heat records were broken in Texas just last week on August 13th.

The fact that the worst US West Nile epidemic in history happens to be occurring during what will likely prove to be the hottest summer on record doesn’t surprise epidemiologists. They have been predicting the effects of climate change on West Nile for over a decade. If they’re right, the US is only headed for worse epidemics.”

Attributing ongoing and recent climactic events wholly to climate change is a tricky business, but some scientists are doing just that with recent extreme heat and drought events, including last year’s record drought in Texas.