Mary Fallin meets with a worker at a July 2015 event commemorating Oklahoma Gas & Electric's new solar farm in Oklahoma City.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Mary Fallin meets with a worker at a July 2015 event commemorating Oklahoma Gas & Electric's new solar farm in Oklahoma City.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Mary Fallin meets with a worker at a July 2015 event commemorating Oklahoma Gas & Electric's new solar farm in Oklahoma City.

Oklahoma is synonymous with energy. It’s a major oil and gas state and one of the country’s leaders in wind power. But Oklahoma has been slow on solar energy, and experts say that’s because of state policy — not the sun.

Lawmakers, local business and community leaders, and workers in hardhats on July 27 gathered beneath a tent to celebrate the opening of a new solar power project in west Oklahoma City.

The guest of honor, Gov. Mary Fallin, arrived in an electric Nissan Leaf and made a few short remarks.

Adding “solar power into our energy mix in our state is truly a great accomplishment and something I’m very excited to see,” Fallin said, before throwing a fake switch and ceremoniously “energizing” Oklahoma Gas & Electric’s new solar farm.

The project is split in two parts and was built on both sides of the Mustang Power Plant, a 482-megawatt natural gas-fired steam unit built in 1950. That means OG&E’s newest power source was built on the grounds of its oldest. Renewable energy shares a field with fossil fuel.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

The north section of the solar farm, which will go into service soon, has 8,000 sun-tracking solar panels capable of generating 2 megawatts. The half-megawatt south farm has 2,000 stationary panels and went online in May 2015. Combined, the fields of solar panels generate enough electricity to power around 500 homes, says Scott Milanowski, OG&E’s director of engineering, innovation and technology.

“This is a bit of a science experiment for us, it’s our first entry into solar power,” Milanowski says on a tour of the south farm. “We also last summer put solar panels on two of our buildings.”

Solar energy can be collected or concentrated to heat water for homes or power steam generators, but the most common way to get the sun’s energy onto the electric grid is through photovoltaics — solar panels — installed in big arrays or on a smaller scale on roofs of homes and buildings.

OG&E is studying both, including solar power generated by the utility itself — and solar power added by residential customers. Milanowski says Oklahoma has abundant solar power potential.

“We’re standing out here on a bright, clear, blue day and the sun is going to be providing excellent output,” he says. “It’s interesting because Oklahoma is a little bit behind the curve as far as installing solar with regard to a lot of the rest of the country.”

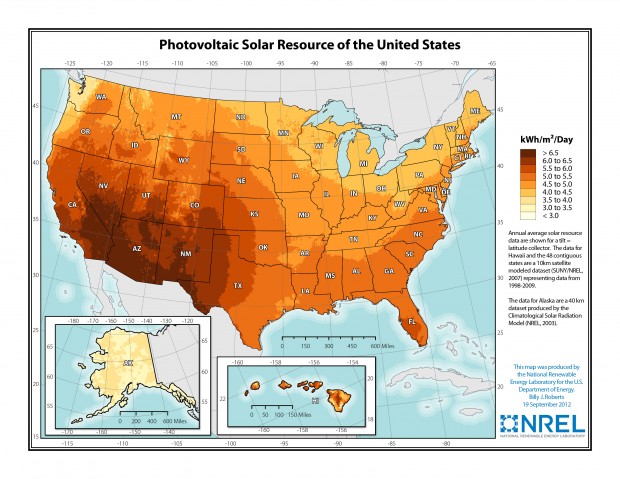

U.S. Department of Energy / National Renewable Energy Laboratory

Oil and gas is king in Oklahoma, but it’s also a heavyweight in wind power. The state is No. 4 in installed wind power capacity. When it comes to solar energy, however, the Sooner State ranks near the bottom. Researchers say Oklahoma has plenty of sun, but the resource is blocked by state policies.

Solar energy potential varies from state to state and is most concentrated in southwestern states like Arizona, California, New Mexico and Nevada. But the sun’s intensity is a relatively small part of the solar energy equation, says Tyler Ogden, a solar analyst at Boston-based Lux Research.

“What’s really key in the adoption in solar on a state-by-state level is the policies that are in place,” he says.

To explain the differences, Ogden compared Oklahoma to Massachusetts.

Massachusetts averages about 3.5 “sun-peak” hours a day; Oklahoma averages 5 to 6. But despite having less solar potential, Massachusetts ranks No. 6 in solar capacity. Oklahoma ranks 45th.

“Oklahoma currently has some policies that are acting as barriers to the adoption of solar or acting as weights that are preventing the establishment of a foundation for the emergence and growth of a solar market,” Ogden says

Ogden says top solar states are more aggressive with tax incentives and environmental mandates for renewable energy. They also make it easy and cheap for individual customers to add solar to the power grid.

Fees levied on electric customers who want to generate electricity with rooftop solar panels — known as distributed generation — can discourage solar growth, Ogden says. Oklahoma recently enacted a law clearing the path for utilities to impose such charges, which they argue is fair because it helps offset expensive electrical distribution technology and infrastructure.

But Ogden says the biggest driver in solar energy growth around the country — especially residential solar — is due to “third-party ownership”

“That’s usually through a lease model or what’s called power-purchase agreement where a homeowner or business would buy the electricity by the kilowatt-hour from the owner of the system,” he says.

A homeowner, for example, could get cash or credit for the electricity without having to pay to install and maintain the solar panels.

Oklahoma is one of a few states that block such arrangements. Ogden says third-party ownership is one reason Texas, which has comparable solar energy potential, is a top solar state and Oklahoma isn’t.

There’s another reason Oklahoma has been sluggish on solar: Electricity prices. Oklahoma has some of the cheapest power in the country.

On average, Oklahoman’s pay 7.54 cents a kilowatt-hour for electricity, data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration show. The U.S. average is 9.84 cents a kilowatt-hour.

“We’ve got relatively low prices for electricity and we don’t have the state mandates to put this in,” OG&E’s Milanowski says. “We’re doing this voluntarily. We’re doing this on our own dime.”

Ogden, the solar analyst, says inexpensive electricity means fewer people are interested in seeking out new sources of energy — and fewer people are willing to pay for the technology to collect it.