Tulsa Union high school teacher Brittney Johnson (left), a student (middle) and student teacher Jenna Todd (right) watch a short video before an activity on the Mayan civilization.

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

Tulsa Union high school teacher Brittney Johnson (left), a student (middle) and student teacher Jenna Todd (right) watch a short video before an activity on the Mayan civilization.

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

How dire is Oklahoma’s teaching certification crisis?

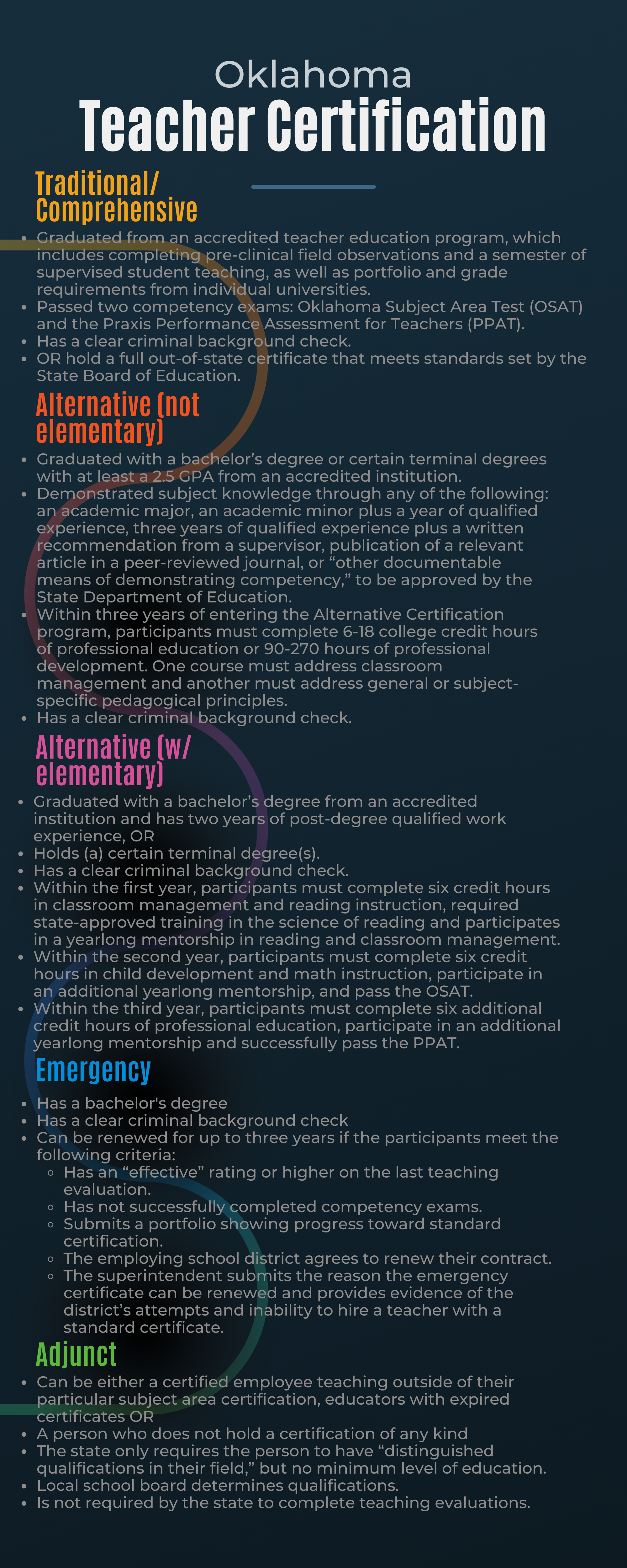

Oklahoma’s teacher shortage led to a record-breaking 3,780 emergency teaching certifications issued in 2022. In 2020, the legislature expanded the program to allow for renewals for up to three years.

The passage of SB1119 during last year’s legislative session underlined the crisis, sparking controversy about how prepared educators should be before they’re in front of children. The bill allowed adjunct teachers — whose qualifications are set by each district and who are not required by the state to attain a certain education level — to work up to full-time hours.

From 2001-2018, Oklahoma’s enrollment in university education programs dropped by 80%. That decline caused Oklahoma City University to phase out its early childhood and elementary teacher preparation programs altogether.

As schools struggle to fill classrooms with teachers holding standard teaching certificates, provisionally certified teachers have had to step in to fill the gap. But do students lose out when hiring traditionally certified teachers becomes a luxury this teacher-strapped state can’t afford?

‘A learner of learners’

Jenna Todd is a Northeastern State University social studies education senior who dreams of running her own classroom someday. She said before her cohort began student teaching, they were honored at a teaching certification ceremony. For Todd, it underscored the importance of not only what she was doing, but how she was doing it.

“It was like a celebration of going into the teaching program and to become teachers. And it felt really good,” Todd said. “Because you think about other students, business majors or art majors, and even though what they’re doing is absolutely amazing, and go pursue your dreams! But here we’re actually being celebrated like we’re firefighters or something. And it makes you feel thankful for what you’re doing, and that it’s important.”

Todd has just finished her first week as a student teacher at Tulsa Union High School, mentoring under Brittney Johnson — a 9th year educator. As students wrote summaries about the Mayan civilization on colored paper, Johnson repeated her instructions for the assignment in Spanish for the English Language Learning students in the class.

In Johnson’s classroom, she said she’s learning how to reach all students, regardless of ability or language.

“I’m really thankful I’m in a classroom right now with many [English Language Learning] students, because that is something that worries me. I don’t know how I’m going to go into a future classroom with a language barrier,” Todd said. “And so now that I see Ms. Johnson and the different assignments she’s giving that work specifically well for ELL students, for [students with disabilities on Individualized Education Plans], then I can take them into my classroom.”

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

Student teacher Jenna Todd helps a student during a lesson on ancient Mayan practices. Todd says she plans to stay in Oklahoma to teach after her graduation in the spring.

Language barriers are one of the many curveballs teachers have to learn to field. Aiyana Henry, associate dean for professional education at the University of Oklahoma, said students who go through the traditional certification process — OU calls this “comprehensively prepared” — are well-equipped to handle the rigors of being an educator.

“You really become a learner of learners,” Henry said.

Henry said OU’s curriculum is backed up by a variety of strategies based on research and experts in the field, “just like you would do in any field.”

“You would study the methodologies and best practice instructional strategies if you were studying to become a nurse or if you were studying to become a surgeon,” Henry said. “And it’s important that you practice those skills before you actually go into that operating room.”

Comprehensively prepared teachers are more effective educators, and the numbers bare that out:

OU, like many other universities around the country, is experiencing a decline in enrollment in teacher education programs. While no one culprit is behind the decline, several factors play a part: burnout — made especially worse by pandemic stress; low pay; student behavioral issues; and lack of respect from the parents and/or the public.

In a 2019 White Paper written by education professionals at eight different Oklahoma universities, authors lay out the argument for valuing comprehensive university teacher preparation. One key contention in the paper is addressing the problematic narrative that “deprofessionalizes” teaching and teachers, leading to fewer young people seeing teaching as a worthwhile career.

“The notion that preparation is not required to teach has been utilized to justify the exponential growth of emergency certification; the idea that ‘all a teacher needs is kindness’ is disrespectful to our profession,” the paper reads.

Henry said she acknowledges the crucial gap that emergency certified teachers are filling and is grateful for their service. But the proliferation of these certifications in Oklahoma sends a message about the value of preparation.

“It can be a little bit deprofessionalizing when you know that maybe the person next to you, however good the intentions are, didn’t go through the same preparation process, didn’t take out the school loans or didn’t invest that time,” Henry said.

Even in the state’s current educational climate, Henry said teaching is still a worthwhile and vital profession, and her university and the state have made moves to attract and retain qualified teachers. She said it’s time to change the narrative around teaching in Oklahoma.

“I think it’s a great time to become an educator at different institutions,” Henry said. “It’s one of the most rewarding and most impactful jobs and careers that you can get into.”

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

Student teacher Jenna Todd listens as her mentor teacher describes an assignment. Todd said school districts have been clamoring at job fairs to attract university-prepared teachers.

‘Far more to teaching than just liking children’

Forty-three year educator and Midwest City Republican Sen. Brenda Stanley can recount every pivotal teacher she’s ever had — and there have been a lot. She said the most impactful teachers were more than just instructors.

“My first grade teacher was Mrs. Taylor. I will never, ever forget her,” Stanley said. “My sister had to have her appendix removed. So back then, you put them in the hospital for a couple of days. My first grade teacher let me come live with her while my sister was in the hospital.”

Stanley went on to teach in Georgia, Arkansas and Mississippi before coming to Oklahoma. She was a traditionally certified teacher who also obtained a master’s degree in education and administrator certification. And while working at UCO, Stanley supervised student teachers.

She said she knows the value of adequate teacher preparation first-hand.

“I had a really strong background before I ever stepped foot in the classroom on my own. So my fear is that we’re putting people in front of a classroom full of children, and we’re not providing the support that we need for them to be successful,” Stanley said. “And I know that we have people coming up to us in the legislature, ‘We got a teacher shortage, we have to have someone in the classroom.’ I understand that. But we want well-trained, qualified people in the classroom.”

University programs teach future teachers techniques such as navigating special education requirements and state-mandated standards, understanding educational pedagogy and psychology, preparing lesson plans, working with parents and helping students through trauma or abuse.

“There’s far more to teaching than just liking children, you know?” Stanley said.

Without that training, Stanley said she’s concerned whether Oklahoma’s kids are getting the highest quality of education they could be.

Stanley is authoring several bills this legislative session aimed at supporting teachers — one of which is SB48, which would expand the state’s mentor teaching program. Under her bill, highly qualified master teachers would mentor new teachers for their first three years and receive a $2,000 per year stipend.

Other lawmakers are also trying to attract and retain educators this session through new legislation, including:

As another legislative session begins to get underway, lawmakers like Stanley still hope Oklahoma can bounce back from its teacher crisis and jam the revolving door of emergency certifications. Quality educators, she said, should know how valuable they are.

“It is such a responsibility and a role that you play in a child’s life,” Stanley said. “We have to be serious about who we’re putting in front of the classroom.”