Mark Gardiner stands on his family's generational grassland prairie ranch. Gardiner contracted with Common Ground Capital in June 2022 to maintain a permanent conservation easement.

Beth Wallis/ StateImpact Oklahoma

Mark Gardiner stands on his family's generational grassland prairie ranch. Gardiner contracted with Common Ground Capital in June 2022 to maintain a permanent conservation easement.

Beth Wallis/ StateImpact Oklahoma

Following November’s decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list the Great Plains-based Lesser Prairie-Chicken under the Endangered Species Act, conservation organizations are expecting a boom from energy companies adapting to new protections and landowners volunteering their acreage for habitat.

The Lesser Prairie-Chicken is a grouse living in the southern and central high plains of the U.S. It’s known for its elaborate mating dance in which males raise their feathers, gobble and stomp their feet at a rate of up to 17 stomps per second, creating a drumroll on the prairie ground.

About 90% of the chicken’s historical range no longer exists, and according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), the grouse’s population numbers are concerning: of the two separate populations of Lesser Prairie-Chicken, one is likely to go extinct and the other is likely to become endangered in short order.

Courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

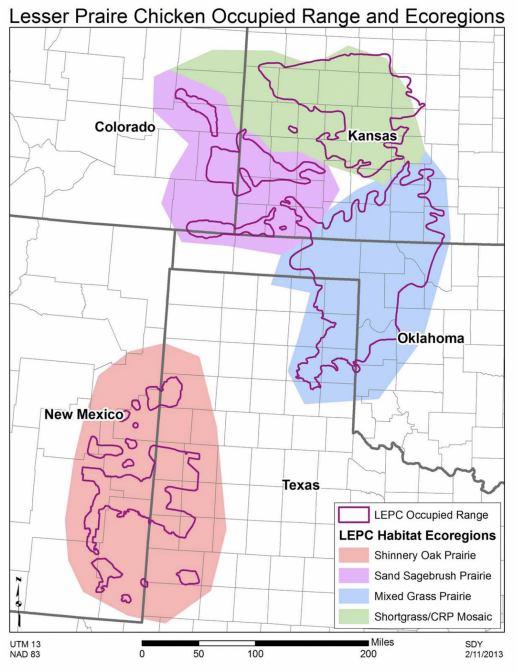

The habitat range of the Lesser Prairie-Chicken.

In June 2021, the USFWS proposed to list the bird, though it missed its June 2022 deadline to do so. In November 2022, it listed the Northern population — which lives in Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma and Texas — as threatened and the Southern population — which lives in Texas and New Mexico — as endangered.

A “threatened” listing means the USFWS believes the species will likely become endangered in the foreseeable future. An “endangered” listing means the service believes the species will likely become extinct in the foreseeable future.

But even though the Northern population is listed as threatened, the Service said it believes the bird is at risk of extinction in the foreseeable future. Because of this, the USFWS’s protections for the Northern population mirror those of the Southern population, with a few exceptions.

Well before the recent decision to list the chicken as threatened and endangered, Common Ground Capital was knocking on doors of ranchers, trying to convince them to share their land with the Lesser Prairie-Chicken — and get paid for it.

Common Ground Capital operates permanent conservation easements, which are protected, privately owned pieces of land that serve as prime habitat. Landowners agree to maintain the land and are paid through a system of conservation banking, which means industries purchase mitigation credits that allow them some leeway to develop near Lesser Prairie-Chicken habitats.

Wayne Walker, Principal of Common Ground Capital LLC, said energy and telecommunications industries are its primary customers for buying Lesser Prairie-Chicken mitigation credits. Lesser Prairie-Chickens are averse to tall structures where birds of prey can stalk them, so the presence of phone wires, wind turbines and oil rigs drives the chickens away — further fragmenting their habitat.

Walker said ranchers near one of their easements at the Gardiner Angus Ranch are starting to take notice of the increased demand on mitigation credits. More credits bought means more protected habitat for the Lesser Prairie-Chicken, and more money in landowners’ pockets.

“I think what’s happened is because of all the press on the Prairie Chicken, the Gardiners are certainly getting calls from their neighbors. ‘Hey, I know you did this crazy Prairie Chicken thing, I saw the news. What’s up?’” Walker said. “We hope over time that as we expand beyond the Gardiners and other landowners and Kansas and Texas and New Mexico and hopefully even Oklahoma again soon, that more and more landowners will see this model as a win-win.”