What more can be done to save the Lesser Prairie-Chicken?

-

Beth Wallis

Mark Gardiner’s ranch in southwestern Kansas has seen a few changes over the last 130 years it’s been in the family. What began as a 160-acre homestead would eventually swell to more than 48,000 acres of ranchland where Angus cattle can be seen grazing under a seemingly endless sky.

But one thing has stayed constant at the Gardiner Angus Ranch: the presence of a certain rare, dancing bird — the Lesser Prairie-Chicken.

Beth Wallis/ StateImpact Oklahoma

Mark Gardiner stands on his family’s generational ranch.

“There’s prairie chickens over our entire ranch, and I’ve seen them ever since I was a kid,” Gardiner said. “Fortunately, this is one of the largest and one of the best prairie chicken populations — not only in Kansas, but anywhere.”

The Lesser Prairie-Chicken is a grouse living in the southern and central high plains of the U.S. It’s known for its elaborate mating dance in which males raise their feathers, gobble and stomp their feet at a rate of up to 17 stomps per second, creating a drumroll on the prairie ground.

This June, part of the Gardiner Angus Ranch became an official safe haven for the imperiled bird. Through the use of a permanent conservation easement, Gardiner gave up his family’s development rights for part of the land — guaranteeing its status as a permanent, maintained habitat for the grouse. Habitat fragmentation has been one of the main drivers of the bird’s population decline.

About 90% of the chicken’s historical range no longer exists, and according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), the grouse’s population numbers are concerning: of the two separate populations of Lesser Prairie-Chicken, one is likely to go extinct and the other is likely to become endangered in short order.

In June 2021, the USFWS proposed to list the bird — a move that would’ve triggered significant federal protections for it. However, the Service has yet to finalize its proposal to do so, despite its June 2022 deadline.

While the USFWS initially agreed to an interview for this story, the Service was not able to schedule it before publication.

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

The landscape of the Gardiner Angus Ranch. The ranch is prime prairie chicken habitat, with plenty of grass, shrubs to provide cover from the sun and no tall structures that predatory birds can hide in.

Now, the USFWS is facing a lawsuit from the Center for Biological Diversity for delaying the prairie chicken’s status listing, despite a recent aerial survey showing a 20% decline in the bird’s population over just the last two years.

Given the bird’s major habitat areas in prime oil and gas country, Michael Robinson with the Center for Biological Diversity said the delay comes down to one thing:

“Political influence,” Robinson said. “When animals and plants are squeezed into some of their last homes and their previous habitats have already been developed, their remaining habitat is often desired to be exploited by corporations. (…) And in the case of the Lesser Prairie-Chicken, the energy development, agriculture, [and] so many causes have led to its decline. As in so many other cases, political influence delayed it to the point where extinction becomes a lot more likely.”

According to the Endangered Species Act, listing determinations are to be based solely on the best scientific and commercial information available – and not economic impacts.

If the USFWS ultimately decides to list the Lesser Prairie-Chicken, industries will be required to mitigate their development impacts through conservation measures. But if the delay continues or the bird is never listed, advocates say this rare, dancing bird is running out of time.

Where did the Lesser Prairie-Chicken go?

This isn’t the first time the Lesser Prairie-Chicken has become a candidate for the Endangered Species List.

The USFWS listed the bird as threatened in April 2014. That means the Service believed the species would likely become endangered in the foreseeable future. In 2015, that decision was reversed after significant pushback from the oil and gas industry, and in 2016, the grouse was delisted by the Service.

In a lawsuit, the Permian Basin Petroleum Association and four New Mexico counties argued the Service didn’t account for the existing conservation efforts already at work.

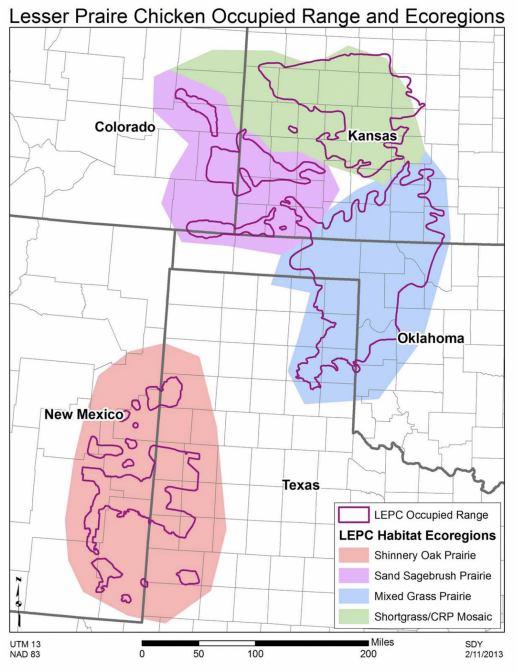

Courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

The habitat range of the Lesser Prairie-Chicken.

Other conservation efforts have stepped in, in lieu of an endangered listing. The USDA created a Conservation Reserve Program where landowners get paid to not use their land for crops, but rather to plant native grasses and forbs to benefit dwindling species populations.

While the program has shown success in expanding habitat range for the prairie chicken, it’s facing significant long term challenges due to contracts with landowners only lasting 10-15 years. Enrollment in the program has dropped every year for 13 years straight.

Current numbers are close to where they were when the program began, in part due to the USDA slashing payments to landowners. Without enough financial incentive to turn down oil and gas development or use the land for farmland, advocates and researchers worry the gains made through the program over the years will be short-lived.

Wayne Walker serves as the Principal of the conservation organization Common Ground Capital LLC, which manages the easement at the Gardiner ranch. He said it often comes down to money.

“Landowners wake up every morning and they’ve got to make a living on their ranch. And if someone knocks on their door willing to pay down for some of their services or willing to buy their ranch and develop it, that’s a market-based discussion,” Walker said. “You’re competing with wind development, you’re competing with ranch development, you’re competing with livestock, etcetera.”

Another strategy comes from the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA). In 2013, WAFWA, in partnership with state fish and wildlife agencies, finalized a Range-wide Conservation Plan and later developed a companion oil and gas Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances in 2014.

Through that, oil and gas companies sign agreements to limit development impacts of projects located within Lesser Prairie-Chicken habitats and to mitigate “unavoidable” impacts. Private landowners sign agreements through WAFWA to restore and manage their land so it benefits the species. Those landowners are paid from a system in which industry developers voluntarily purchase mitigation credits.

But according to a 2019 audit ordered by WAFWA, the agency’s mitigation plan was fraught with issues.

The audit raised questions of significant financial mismanagement and found that because of temporary conservation contracts and undercharging for mitigation fees, among other issues, “the program as currently structured and operated does not provide a net gain in conservation.” WAFWA’s itemized response to the audit can be found here.

According to the Center for Conservation Innovation at Defenders of Wildlife, over 200,000 acres of impacts have not been mitigated by WAFWA. The Center estimates almost 1 million acres of Lesser Prairie-Chicken habitat has been lost or fragmented for oil, agriculture and other commercial development.

WAFWA declined an interview with StateImpact, but responded in an email:

“Our operations under the [Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances] are transparent and continue to operate under full compliance of the permit issued for our CCAA,” wrote Zach Lowe, the executive director of WAFWA. Lowe provided a link to the organization’s most recent annual report, which said WAFWA is currently in compliance with 26 of the 27 requirements for the agreement.

There are other conservation efforts for the Lesser Prairie-Chicken, including a variety of state-based initiatives. But according to the Species Status Assessment from the USFWS, Lesser Prairie-Chicken population decline is expected to continue “even when accounting for ongoing and future conservation efforts.”

Though the USFWS could designate Lesser Prairie-Chicken range as critical habitat — which provides significant federal protections for habitat land but also creates headaches for developers — and said it is “prudent,” to do so, the Service said that designation isn’t “determinable at this time.”

The business of conservation

At the Gardiner Angus Ranch, a different kind of conservation game is at play. Though it took 10 years of negotiations, Mark Gardiner worked with Common Ground Capital to come up with an agreement for a permanent conservation easement that will exist for the Lesser Prairie-Chicken in perpetuity.

Stephanie Manes is a biologist with decades of experience in Lesser Prairie-Chicken conservation and serves as a consultant for Common Ground Capital. She said with the agreement, a landowner extinguishes their development rights.

“For example, you can’t have a paved parking lot and have conservation values on the same property,” Manes said. “They’re mutually exclusive.”

Once the credits are sold and the easement put down, they go into a trust to fund maintenance projects in perpetuity.

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

Cattle graze on a hot summer day at the Gardiner Angus Ranch in Ashland, Kansas.

Walker, with Common Ground Capital, said of about 15 remaining prairie chicken strongholds left, his organization has four of them under option with landowners. Common Ground Capital has secured 75,000 acres of option agreements across three states.

If the USFWS decides to list the Lesser Prairie-Chicken, Walker predicts more industry participants, including renewable energy, will get on board with Common Ground Capital’s process. For now though, that’s still up in the air.

“Unfortunately, sometimes it takes these regulatory decisions to draw folks to participate,” Walker said. “So obviously, [by delaying the decision] the Service is creating uncertainty for all parties, anywhere they go.”

For Gardiner, the conservation agreement has provided economic assurance for his ranch, even when markets prove volatile.

“Where [ranchers] often get in trouble is when there’s a financial crunch,” Gardiner said. “And so they decide, ‘Well, I need to push it a little bit harder this year,’ or there’s a drought. And of course, it could be economically devastating to sell when prices are low. So that’s one thing that conservation banking can really help with.”

Gardiner said the conservation easement hasn’t changed much of his day-to-day ranch life. He took down some windmill towers and mows the grass, but ultimately, he said he was already taking care of the land. Now, he just gets paid for it.

What’s good for the prairie chicken, he said, is good for him. And while there’s no way to know if the Service will eventually list the bird, his conservation easement, at least, provides this population of Lesser Prairie-Chickens with a permanent safe haven.

“We like the ecosystem to be balanced,” Gardiner said. “If it’s balanced for the wildlife, it’s going to be good for the cattle too. (…) I guess I was fearful at first that, you know, prairie chickens are important, but people are too. And so making sure that the people and the cattle and all that could work together, it became an opportunity that we were excited about and happy to be part of.”

Beth Wallis/StateImpact Oklahoma

The prairie grassland on the Gardiner Angus Ranch meets the seemingly endless sky in Ashland, Kansas.