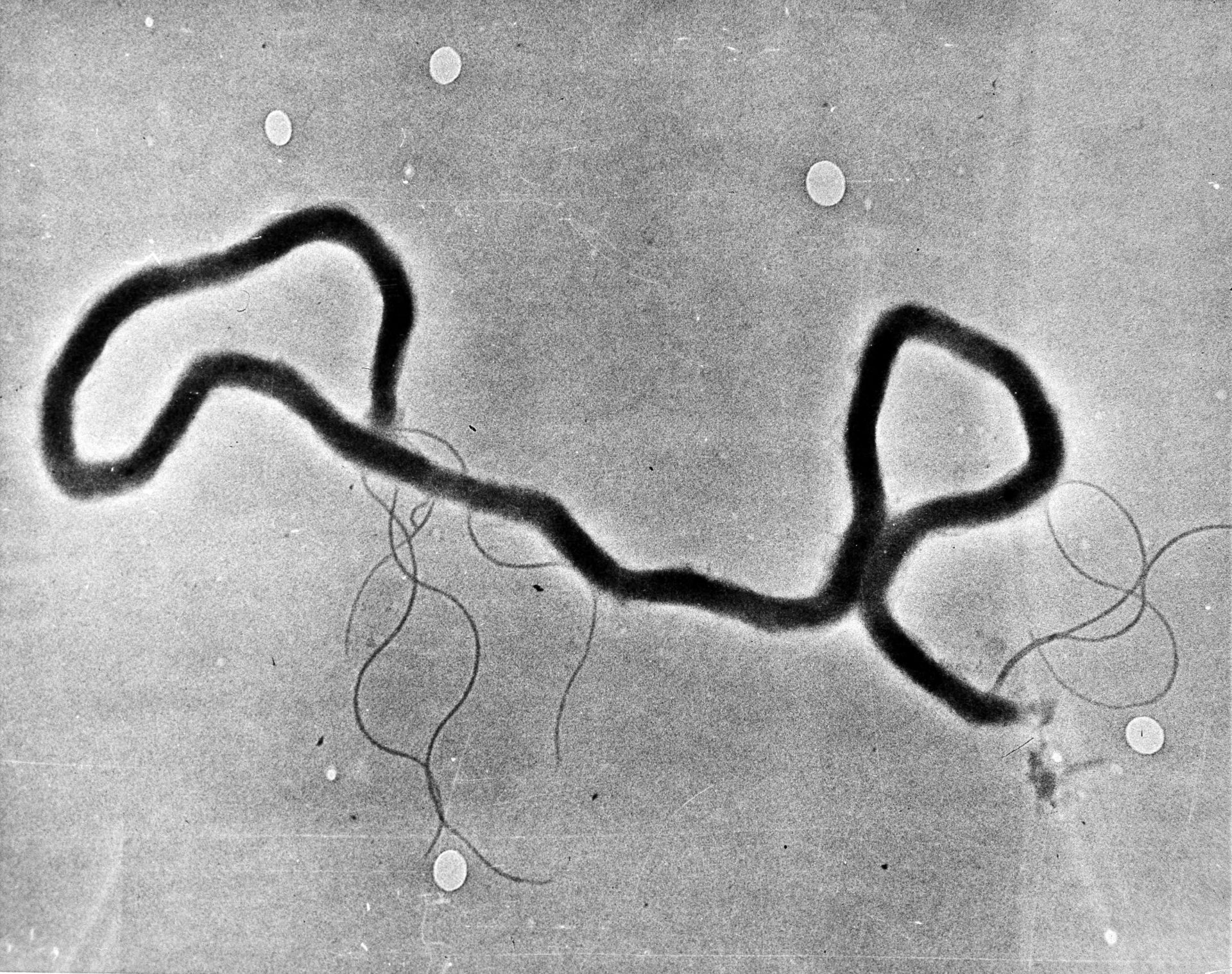

In this May 23, 1944 file photo, the organism treponema pallidum, which causes syphilis, is seen through an electron microscope. (AP Photo)

In this May 23, 1944 file photo, the organism treponema pallidum, which causes syphilis, is seen through an electron microscope. (AP Photo)

For years, syphilis seemed to disappear from the U.S. and from Oklahoma. But in the past decade, cases have been skyrocketing — especially among women and newborns.

There was a nationwide syphilis pandemic in the 1930s and 1940s right before access to antibiotics became common. As many as one in 10 Americans contracted syphilis at some point, and each year, half a million Americans were diagnosed with new cases. Through improved treatment and prevention, case counts dropped to just a few thousand nationwide a year. The disease — known as the ‘great imitator’ because of its ability to present like other infections — had effectively been eradicated.

It’s back, and it’s surging.

Rates are up across the country, and Oklahoma had the 4th highest rate of syphilis infections in 2020. Cases were going up long before the coronavirus pandemic made its way to Oklahoma, but public health workers say that only made the problem worse.

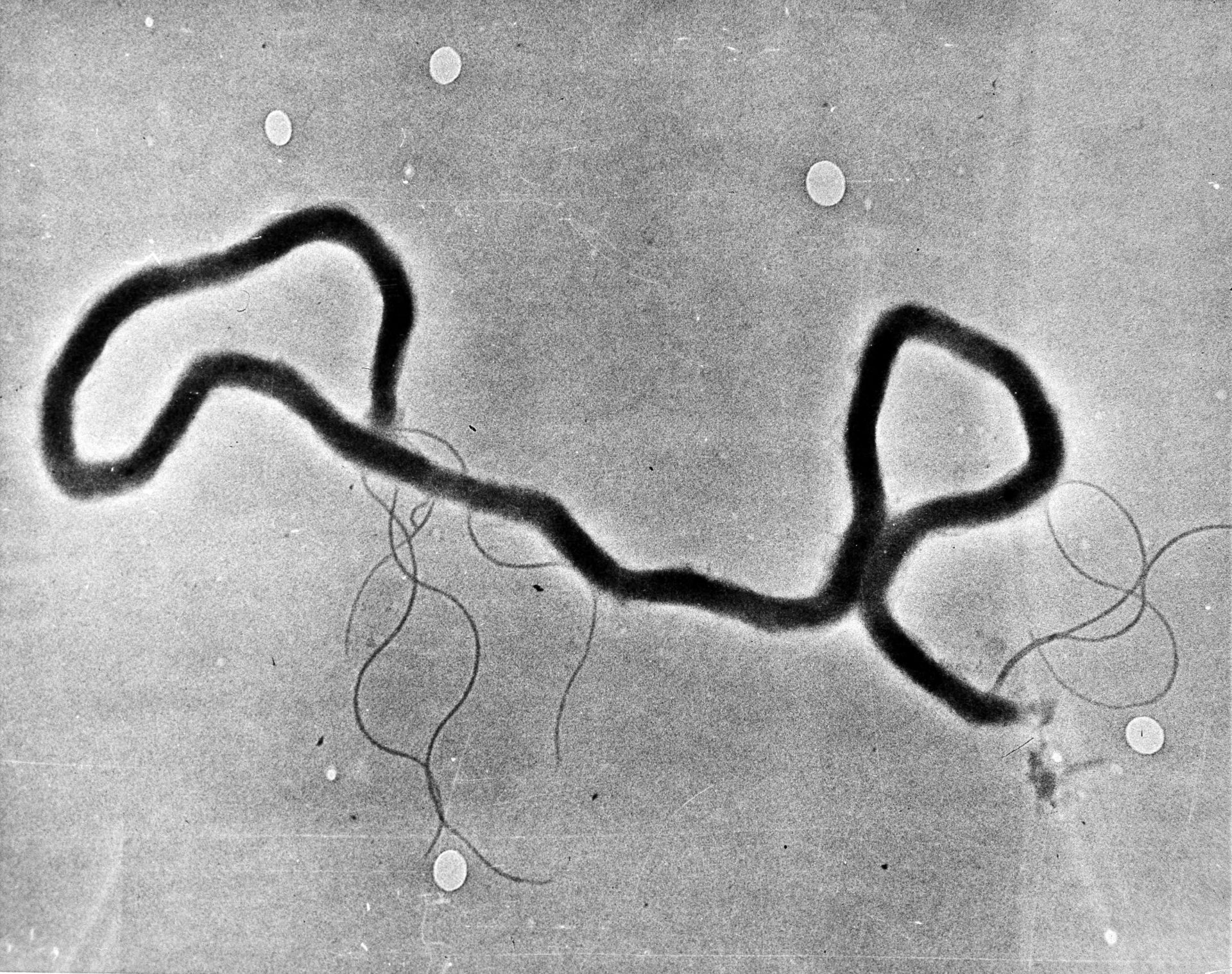

Until a few years ago, the disease was reported mostly among men having sex with men. But that has shifted as cases of it began appearing in heterosexual women. From 2014 to 2018, the number of syphilis cases among women grew eight fold in Oklahoma.

March of Dimes table shows Oklahoma syphilis rates increasing among women.

In Carter County, near the Texas border in central Oklahoma, public health officials began prioritizing efforts to fight that bacterial infection in 2019. Even with mitigation efforts, the county has been experiencing severe outbreaks.

“Our rate, it seems, here in Carter County compared to last year, we’re up 900 percent,” Mendy Spohn told StateImpact in 2020.

Spohn is the State Department of Health’s regional administrative director for the area. Carter County is home to Ardmore, one of the state’s worst hit areas in the opioid epidemic. Public officials were ringing alarm bells in 2018 about a burgeoning influx of heroin, which could be an unintended consequence of opioid crackdowns. Heroin and opioids are chemically similar, and if someone addicted to opioids can’t find a supply of opioids, heroin can stand in.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, drug use — and especially the use of methamphetamine and injection drugs like heroin — is associated with sexual behaviors that increase the risk for acquiring syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. That includes having multiple sex partners or concurrent sexual partnerships, inconsistent condom use and exchange of sex for drugs.

Rebecca Burton is a public health nurse who has been serving the Carter County area for 26 years. She said the surge in drug use has likely caused the county’s syphilis diagnoses to skyrocket, as dealers accept sex in lieu of cash payments.

She also said syphilis poses a particularly difficult public health challenge.

Syphilis can be hard to diagnose.

“It’s not just straight-out disease like (when) you have gonorrhea — throw two pills and the shot at somebody, boom, it’s done,” Burton said.

First, she said it’s hard to identify, mostly because it can lie dormant or present differently in people. The infection has gotten nicknames for how sneaky it can be. Then, it behaves differently at different points of infection, so it’s important to identify which phase it’s in and how to treat that.

Primary syphilis symptoms tend to appear within 90 days. They include ulcers or sores at the infection site. Those symptoms can disappear — seeming to have resolved on their own. Public health workers warn that can lull someone into a false sense of security.

A few months after infection, patients can enter the secondary phase. Without treatment, patients would move to these later stages of infection. It can present as a rash on the hands,feet or other parts of the body, sores in the mouth or as genital warts. Tertiary syphilis occurs after years of untreated infection, and it can damage the circulatory system, the bones, liver and joints. It can impair vision and cause death.

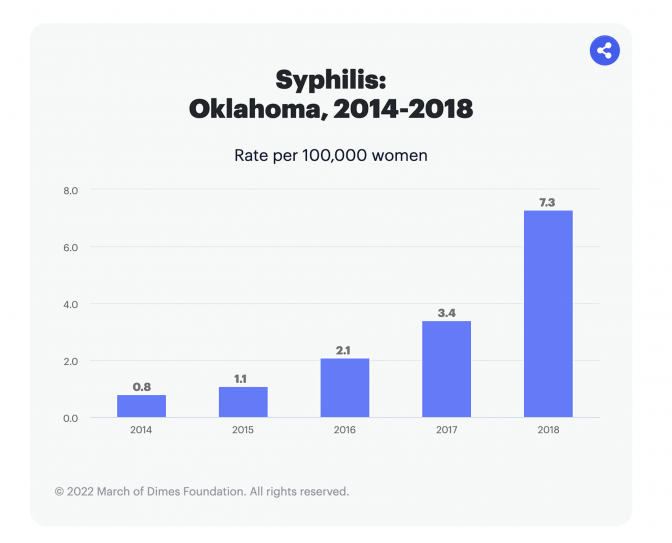

At any stage, syphilis can infect the brain and spinal cord and become neurosyphilis. That can cause dementia-like symptoms, incontinence, tremors, blindness and hearing loss.

A visual guide on ocular syphilis symptoms by the Oklahoma State Department of Health.

To cut down on infections, health workers aim to diagnose and treat the infected, but they also aim to raise awareness about it within the community.

“The general public seems to think that syphilis quit existing many years ago,” Burton said.

Spohn said although health providers aren’t mistaken about the existence of the disease, it might not be top of mind for them. So public health officials are working with partners in care facilities, too.

“We’re having to do a huge provider push to make sure that our emergency rooms, OBGYNs and our other providers are caught up on the medical presentation of syphilis and how to diagnose,” she said.

Terrainia Harris is the administrative program manager for the state’s Sexual Health and Harm Reduction Service. She told StateImpact in May there is another common barrier to diagnosis: stigma. It affects patients who might fear getting tested, but it can also affect providers too.

She says there’s a common story for patients who come in with symptoms and a ring on their finger.

“They ask to be tested for one of the (sexually transmitted) infections, and the physician or nurse or nurse practitioner would tell them, ‘Well, you’re married, you don’t need to worry about that,’ or, ‘You’re not in that population,'” she said. “So there’s still this kind of stigma of a difference between those people that get infections and those that don’t.”

COVID likely made this situation worse.

Ronneal Mathews is the director of community engagement for Thrive OKC, a nonprofit organization that advocates for access to sexual health services.

“I think we’re seeing a lot of the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, really,” Mathews said. “We’re looking at people who had a reduced frequency of in-person health care services and routine visits and screenings.”

Mathews points out people who still seek care face obstacles, too. Early on in the pandemic, providers leaned heavily on telemedicine. Labs had supply and labor shortages – problems felt across most industries.

“People had a lot of lapses in health insurance coverage due to, you know, employment losses and things like that during the pandemic,” Mathews said.

So all of those issues likely worsened the trends, but Oklahoma was already trending high. Harris says on the state level, one infection in particular has been surging.

Babies are being born with syphilis.

“The congenital syphilis rates have been going up — pretty astronomically — for the last several years,” Mathews said. “Since 2017, there’s actually been a 657 per increase in congenital syphilis cases.”

She’s referencing CDC data, which showed in that time, Oklahoma went from 7 cases of congenital syphilis per year to 53.

Congenital syphilis can cause abnormalities in facial features, neurological damage, and skeletal deformities. It can also cause stillbirths.

Oklahoma isn’t alone. The CDC reports nationwide, the rate of congenital syphilis nearly tripled from 2014 to 2018.

The CDC provides guidance on syphilis testing in pregnant people. But Ivonna Mims, the Sexual Health Nurse Manager for the Oklahoma State Department of Health, said while other states have passed legislation to require those screenings, Oklahoma hasn’t.

“There’s not been steps taken to mandate that third trimester and delivery screening in pregnant females,” Mims said. “And so therefore, it’s not getting done consistently.”