Nash Williamson (right) and his father Jamie Williamson pose for a picture at the Oklahoma Youth Expo in Oklahoma City.

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Nash Williamson (right) and his father Jamie Williamson pose for a picture at the Oklahoma Youth Expo in Oklahoma City.

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

School choice was just about the last thing on Nash Williamson’s mind.

It’s a hot button issue in Oklahoma City – where he was visiting to participate in the Oklahoma Youth Expo – a livestock show – at the State Fairgrounds. But it’s really a nascent concept for him and his classmates.

Instead, his mind is on the pigs.

“We’ve got three pigs here with us,” he said outside a stall in a barn filled with squealing hogs. “They’re crossbreed pigs, which is two different breeds put together.”

Nash is a freshman at Sulphur High School. He’s involved in football and agriculture. In fact, it was those two things that attracted him to Sulphur.

But Nash’s family actually lives closer to Wynnewood, a town one whole county north. And he even attended Wynnewood schools up until sixth grade.

But he wasn’t really happy there. He didn’t feel challenged. Nash has two younger brothers, and his dad Jamie Williamson said he and his wife wanted better for Nash and their two younger boys.

“We made the decision as a family, we have to put our children in a better environment for them to reach their potential,” Jamie Williamson said.

So the Williamsons looked around. The family went as far away as Ardmore and Ada to look at potential schools before landing on his top choice: Sulphur.

He said Sulphur was a natural fit with those strong athletics and agriculture programs. Plus, there’s plenty of college level courses.

“When Nash graduates he can actually have up to 18 hours of college credits under his belt, all on campus in Sulphur,” he said. “So his junior year and senior year, instead of just coasting to graduation for those that are motivated and higher achievers, they can have a full semester, possibly even a full year under their belt right there on the campus.”

This is what school choice looks like for many kids in rural Oklahoma.

Though homeschooling appeals to some, it didn’t to the Williamsons. There are very few private school options and they don’t have athletics and ag offerings like at Sulphur. They never thought of looking beyond public schools.

In fact, Sulphur superintendent Matt Holder said before an open transfer law was passed last year, the schools already let kids come and go based on their own personal needs and desires. And though several rural Oklahoma education advocates in this area are quick to call for money for private education or creating more choice, they’re just as quick to say they have no problem with the public school system and recognize its importance to the community.

That’s what made the flyers and TV ads so weird.

Sulphur, with its population of 5,000, is the largest city in Oklahoma House District 22. And because of the man who represents it – House Speaker Charles McCall – it’s become a battleground in a major fight in Oklahoma City over private school vouchers.

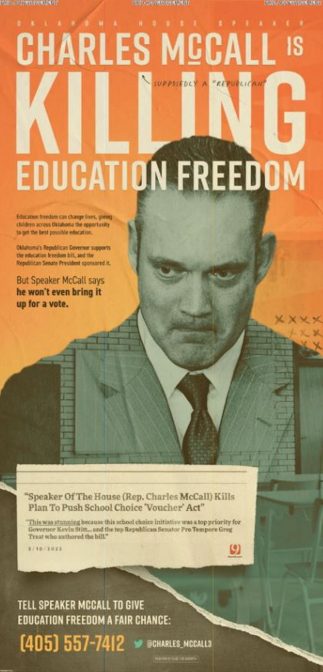

The Oklahoman newspaper

A political ad from the Club for Growth that ran in The Oklahoman newspaper.

Holder distinctly remembers the political mailer.

First of all, it was huge. Like maybe one of the biggest pieces of mail he’s ever gotten. But, one thing especially stuck out.

“I think the return address was the first thing that caught my attention,” he said.

Washington D.C.

The mailers came from Club for Growth. That group spent tens of thousands to attack House Speaker Charles McCall in his district, which stretches across portions of Atoka, Garvin, Johnston and Murray Counties. It also purchased television ad time.

The attacks came over Senate Bill 1647, a controversial school choice measure generating a lot of buzz in Oklahoma City. McCall is against it. Senate Pro Tem Greg Treat authored it, and it has the backing of Gov. Kevin Stitt.

“I pledge to support any legislation that gives parents more school choice, because in Oklahoma, we need to fund students, not systems,” he said at his State of the State address.

The mechanics of the bill works like this: if a family enrolls in an Oklahoma private school they become eligible for a publicly funded Education Savings Account. That account is worth whatever the student’s weight is on the public school funding formula, a massive pot of money that is distributed to public schools across the state.

Homeschool students aren’t eligible after homeschool parents lobbied to be left out. And there is an income cap of 300% of reduced lunch, which means a family of four must make less than $154,000 annually to qualify.

Treat has said the accounts will help students transfer to schools that are better for them as the bill has been debated in committee.

“We are trying to help make sure that we fund students in the best educational environment for their needs,” Treat said.

The bill is expected to be heard next week on the Senate floor. But McCall has repeatedly said that it will go no further.

“The House of Representatives was not approached or worked with to try to craft this policy to get it ready for this session,” he told Ardmore television station KTEN. So there’s just a lot of unanswered questions.”

McCall is incredibly popular in his district. In 2020 nobody challenged him. In 2018, he beat his Democratic opponent by more than 30 percent. So the attacks were confusing for district voters when they hit local airwaves and mailboxes. And he’s gotten that way by listening to constituents, both Holder and Jamie Williamson said.

He’s talked about education legislation with Holder and agricultural legislation with Williamson, they both said.

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Sulphur Public Schools superintendent Matt Holder.

On this bill, Holder said, he’s listened. And Holder believes McCall will continue to refuse hearing SB 1647. After all, it could end up being very costly for Sulphur.

That’s welcome news for rural superintendents like Sulphur’s Holder. Cost estimates for the bill range from $118 to upwards of $160 million. If that money was given to Oklahoma public schools instead, Sulphur would stand to get roughly $350,000.

“Real quick math, that’s six to seven teacher salaries,” Holder said. “That is what we’re looking at.”

The public school campus is the cultural center of Sulphur. Drive through town and you’ll see signs cheering on the Bulldogs everywhere from grocery store windows to bank signs.

“I would hope that our legislators understand the core values that we have in rural Oklahoma and will stand up for those core values, and I think Speaker McCall understands that and has so far put his heels in the ground and said, ‘You know, this is this is not going to happen,’” Holder said.

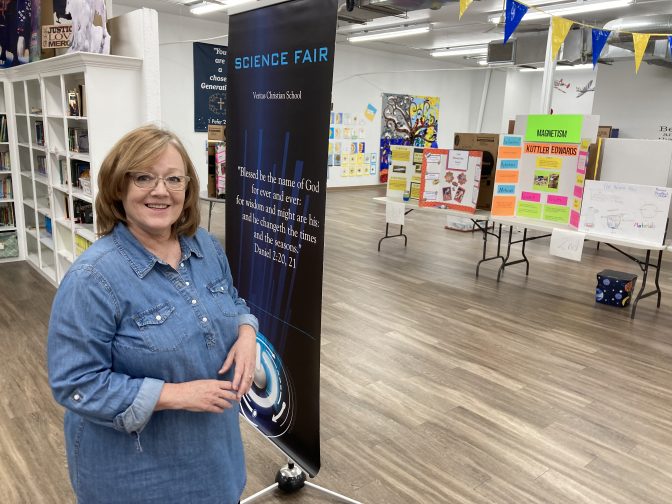

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Donna Abla at the Veritas Christian School science fair.

There is one school in Sulphur where parents would benefit from the bill. That would be Veritas Christian Academy.

And it’s a school where kids don’t just sit around reading the Bible – they do that, founder Donna Abla said – but they also do more.

The school recently hosted a science fair. And the posters look pretty typical.

“They have certain things they have to follow,” Abla said. “They have to have a picture of themselves, the name, the purpose, their Bible verse that goes with their project.”

This is a small Christian school. Abla has purposely never advertised, only letting the school grow based on word of mouth. After roughly a decade in Sulphur, the K-12 private school has 66 students, compared with more than 1,400 that attend Sulphur Public Schools.

Students get very small class sizes. No more than eight to a class. Plus parents like Garrett Leveridge said they know their children won’t be taught to just pass a test. He said the school offers great building blocks for early childhood education for his daughter.

“Smaller class sizes, more individual attention and learning, we felt like she could grow more as a reader, which at this age is almost almost the most important,” he said.

His family would do anything to help his daughter learn.

“Mixed with that would be the Christian aspect of it,” Leveridge said. “Her biblical learning would go along with it.”

Though she said she hasn’t kept up with every evolution of the bill, Abla said she’s supportive of SB 1647. She said she would welcome tuition relief for her students.

“When you go to a private school, you’re paying twice, you’re paying tuition and you’re paying your taxes,” she said.

Tuition here is some of the lowest you’ll find in the state – at one point Abla looked it up and it was the lowest. It costs $375 a month or $3,750 a year to attend school here. And that’s frankly not enough revenue. She estimates Veritas teachers make a third of what local public school teachers can make.

“The teachers are here because they’re committed people,” she said. “They want to help kids and they love teaching. They’re not here to get rich. Look at our cars and know that we’re not here to be rich.”

A majority of families at the school would likely qualify for the program.

But Abla said she is wary of government programs funding private schools in general. She’s only participated in one school voucher program in the past: that would be the Governor’s Stay in School Fund, which gave private school vouchers to students for tuition as part of COVID-19 relief.

Abla said she’s sometimes cautious of school choice legislation because she doesn’t want the government to get too involved in her school. She said she doesn’t want to have to deal with rules, requirements and regulations like they have in public school districts. It could hurt the school’s character and the education it provides.

“No strings,” she said. “We got enough strings. I mean, from Washington to Oklahoma, we don’t need any more strings attached. We don’t need any little things written in at the bottom of a bill that are going to end up hurting us later.”

Crystal Gregory poses for a photo with three of her sons, Louden, “Tiny” and Shaffer Gregory.

Crystal Gregory knows a thing or two about wariness toward government strings.

She’s plugged into the homeschool community and she said, many homeschool parents don’t want to accept government money for their kids education.

“They don’t want to have to answer the government,” she said. “[A] reason why they homeschool, half the time is because they want to do their thing.”

Gregory is a homeschool advocate and currently teaches for Epic Charter Schools from her dining room table on the east side of Sulphur. She’s also a mother of traditional public, Epic and homeschool children.

She actually disagrees with the homeschooling parents who don’t want to accept state money. She’s a teacher at Epic, which has 152 students in Murray County where Sulphur is located and has seen how her students have leveraged the learning fund, which gives $1,000 to students and their families to spend as they choose.

“When you spend your thousand dollars learning fund that you have, your child has the things they need for that year,” she said.

A lot of that money can go to textbooks, which are often better than the books kids might get in public schools that can be years out of date, she says. So when McCall says vouchers aren’t good for rural Oklahoma families, Gregory disagrees.

“There’s two or three hundred other students probably out here that you’re not representing, you know, and I get you do what’s best for the majority, you know, and not the minority,” she said. “But at the same time, like to me, it feels like you’re choosing one child over another.”

Robby Korth / StateImpact Oklahoma

Students gather their cattle for a walk during the Oklahoma Youth Expo.

Regardless of who gets their way on Senate Bill 1647, one thing is clear: In Oklahoma the school choice debate is here to stay.

Parents like Gregory will continue to advocate for school choice legislation.Rural superintendents like Holder say they’ll keep a close eye on these kinds of bills.

And school choice will continue to be an option. If it fails, students will still be able to switch public schools. They’ll be able to enroll in Epic or homeschool. And they can sign up at Veritas if slots are available.

But, bills like it are liable to pop up again, Sulphur superintendent Holder said.

“I feel like it will be a continual fight every year for as long as the rest of my career in education. I don’t necessarily see it going away anytime soon. ” he said.