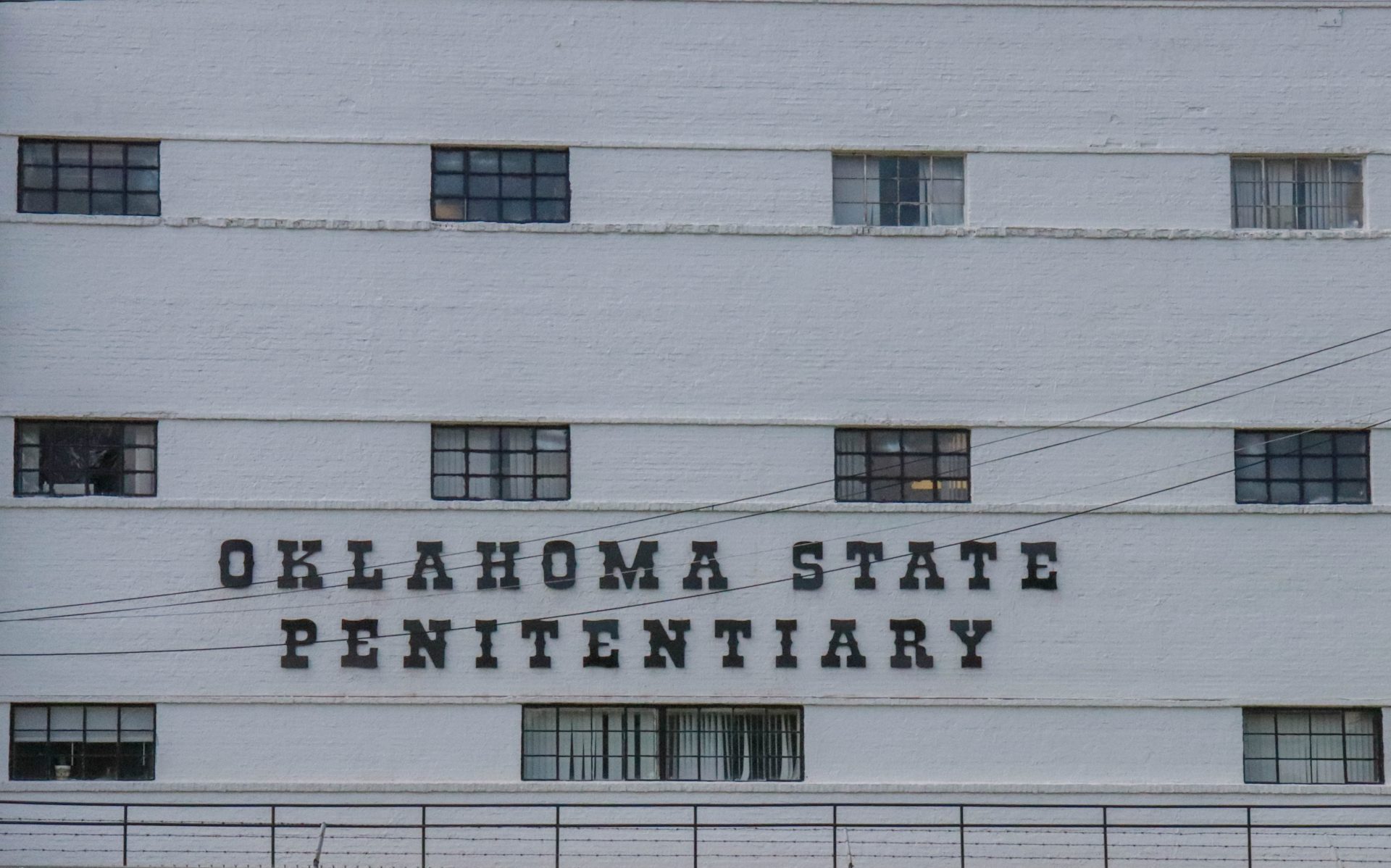

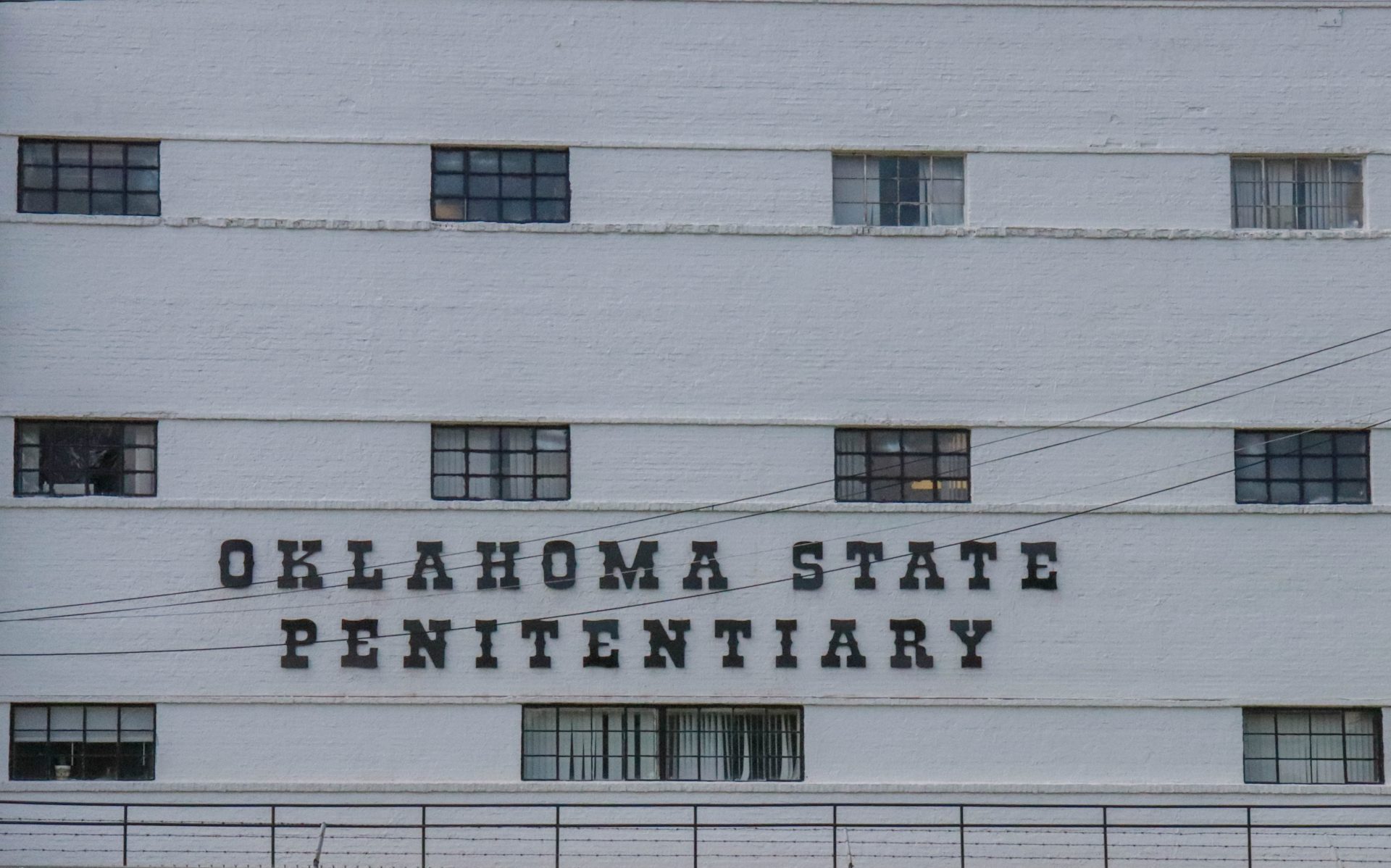

Oklahoma State Penitentiary houses Oklahoma's death row prisoners.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Oklahoma State Penitentiary houses Oklahoma's death row prisoners.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Quinton Chandler / Oklahoma State Penitentiary

Rep. Kevin McDugle invited fellow legislators to Pete’s Place last month for lunch and to explain his belief that Richard Glossip is innocent.

Ten minutes east of Oklahoma State Penitentiary’s white-washed walls, a lunch party converged on Pete’s Place – a famous Italian eatery in Krebs – to discuss the impending execution of Richard Glossip.

State Rep. Kevin McDugle (R, Broken Arrow) stood at the front of one of the restaurant’s private dining rooms forgoing a heavy wooden podium.

“I believe that we’ve got a guy in Oklahoma on death row that’s innocent,” McDugle proclaimed to the room of Democratic and Republican lawmakers.

He’s a Republican and he supports the death penalty, but he says the state has to “get it right.”

Richard Glossip was convicted of hiring an accomplice to murder his boss in 1997. Glossip’s supporters claim he was condemned largely by bad police work, ineffective defense attorneys, false testimony from the actual murderer and dishonest prosecutors – not guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

“We ought to at least have another mechanism if we doubt any part of it, because … we shouldn’t doubt when we put them to death,” McDugle said. “We shouldn’t doubt at all. We should know.”

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Don Knight represents Richard Glossip. He says he has uncovered new evidence and witnesses that debunk the state’s accusations against Glossip.

McDugle, Glossip’s attorney and other advocates brought the bipartisan group of legislators together to rehash the details of the murder and remind them of a bill McDugle proposed earlier in the year. The legislation would have created Oklahoma’s first conviction integrity unit.

Conviction integrity units are legal offices that review convictions. According to the National Registry of Exonerations there are at least 85 in jurisdictions across the U.S.

The same group counts 38 exonerations in Oklahoma since 1989.

McDugle is pushing the bill because of his doubts about Glossip’s guilt and the groundswell of support for death row prisoner Julius Jones.

Angela Marsee is district attorney for Beckham, Washita, Custer, Roger Mills and Ellis counties.

She sympathizes with McDugle’s fears but questions his plan.

“The role of prosecutors is ultimately to ensure justice in … all of our criminal cases,” Marsee said. “We have a duty and obligation, and a responsibility to take special precautions to prevent and rectify the conviction of any innocent person.”

Marsee isn’t opposed to a conviction integrity unit but if the state makes one, she says it will need to carefully gather input from multiple sides of the justice system. She says it has to be properly funded, have sufficient resources and it should operate on established best practices.

McDugle’s bill failed to clear early legislative hurdles but he plans to reintroduce it in the next session.

The bill would’ve created a conviction integrity unit inside the state’s Pardon and Parole Board that could initiate investigations of capital murder convictions on its own or whenever a prisoner submitted a petition with a “plausible claim of innocence.”

The claim would have to be backed up by new information or evidence, and it would have to be an issue the unit could investigate and resolve. The bill also required a prisoner to have exhausted their options in court.

Reports on the unit’s findings would be sent to the Pardon and Parole Board, the Attorney General, the prosecutor who handled the case at trial and the defense.

Angela Marsee thinks there are better ways to set it up.

“I’m not aware of any conviction integrity unit in the United States being placed with a pardon and parole board,” Marsee said.

Most units are in prosecutors’ offices and Marsee says that makes more sense. She believes prosecutors’ offices have better infrastructure for vetting cases. She also thinks the bill’s burden of proof for determining which cases get reviewed is too low.

Cynthia Garza has some suggestions. She is head of a nearly 14-year-old conviction integrity unit in Dallas County, Texas.

There is some debate on best practices for these units, but Garza recommends adopting at least three standards.

First, she says the people in charge of units have to be invested in their mission to find and rectify wrongful convictions.

Next, she recommends a unit report directly to a district attorney. Her own unit is based inside the Dallas County District Attorney’s Office. Garza stresses that the unit must have independence to find success.

“I think it really depends on the leadership, not just of the unit, but of the office,” she said.

Garza thinks prosecutors’ offices are good fits for integrity units because prosecutors have access to resources others don’t. They can get ahold of the state’s case files, police records and defense files. Prosecutors also have the power to secure legal representation and protection for witnesses.

Garza’s team uses a straightforward process to decide which cases to investigate.

“You look for the red flags,” she said. “Was this case only based on eyewitness I.D.? Was there anything else corroborating this person’s guilt?”

Did the state rely heavily on jailhouse informant testimony? These are common examples of conditions that led to wrongful convictions around the country.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Rep. Kevin McDugle toured death row inside Oklahoma State Penitentiary with a group of lawmakers after explaining his thoughts on Richard Glossip’s case.

After lunch, McDugle and his legislative guests visited Oklahoma State Penitentiary’s death row unit.

“The cells are so thick, it’s a thick glass and so you might hear somebody yelling on the other side, but you can barely hear them yelling,” McDugle said.

McDugle purposely wrote his bill to shield a conviction integrity unit from the influence of prosecutors, the Attorney General’s Office, the governor and the Pardon and Parole Board.

To help explain why, he pointed to the district attorney who prosecuted Richard Glossip.

“Bob Macy, his goal was to be the number one guy in the country for death row,” McDugle said.

Bob Macy won death sentences for 54 people throughout his career – courts later reversed nearly half of those sentences.

Macy’s career faced heavy scrutiny after the work of Joyce Gilchrist – a former Oklahoma City police chemist – was discredited. Gilchrist worked with Macy on multiple criminal cases. The Innocence Project says her testimony helped convict 10 people who were later exonerated.

Marsee says she and other prosecutors may be willing to work with McDugle on his legislation next year, but she worries that he is mostly interested in finding a way to help Richard Glossip – not find answers to systemic problems.

McDugle says his bill is about Richard Glossip and Julius Jones but it’s mostly about making sure innocent people aren’t killed by the state.