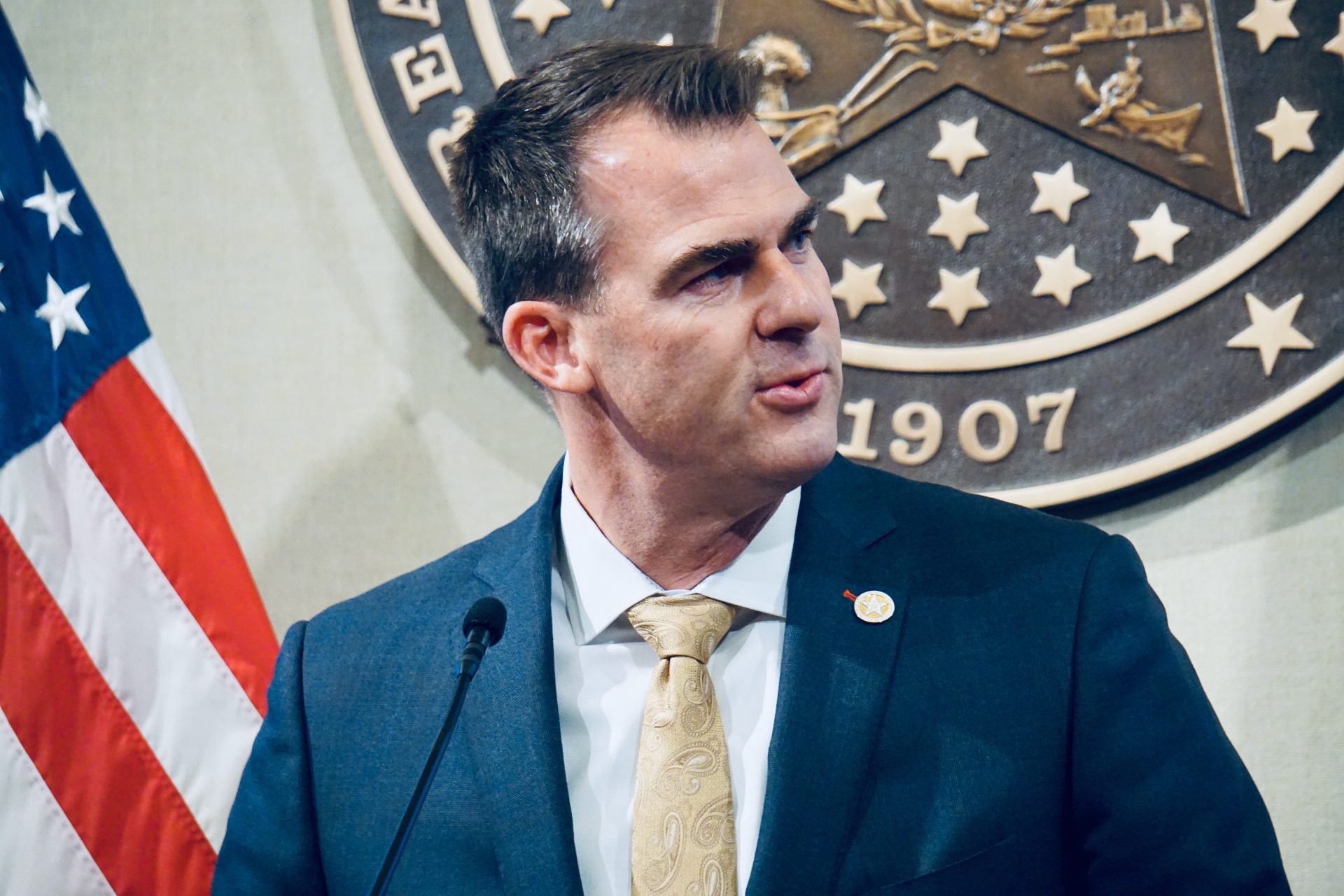

Gov. Kevin Stitt said during a Jan. 29 press conference that Oklahoma needs to improve its health outcomes, which now rank 46th in the nation. Photo by Ben Felder, The Frontier.

Gov. Kevin Stitt said during a Jan. 29 press conference that Oklahoma needs to improve its health outcomes, which now rank 46th in the nation. Photo by Ben Felder, The Frontier.

Oklahoma is fundamentally transforming how it uses Medicaid, despite major opposition from the medical community and from the Legislature.

Medicaid is the program that uses state and federal funds to offer low-income Oklahomans health coverage. Here, it’s called SoonerCare, and by next year it is expected to cover about a million people — one in four Oklahomans.

Stitt’s plan — known as managed care — will shift $2 billion in Medicaid funding to four private health insurance companies, tasking them with coordinating care for about 700,000 Oklahomans. In essence, instead of paying doctors and hospitals directly, Oklahoma will be giving these companies a monthly allowance for each Medicaid member using their services. That managed care program will be named SoonerSelect.

Supporters say the program will improve health outcomes in Oklahoma, which rank among the worst in the nation. Stitt discussed the policy in his most recent State of the State address, which he delivered before the Legislature on Feb. 1.

“America’s Health Rankings puts Oklahoma 46th in the country in health outcomes,” he said. “We’re one of the worst in the country in obesity and diabetes rates. We have the third most deaths from heart disease. That’s unacceptable to me, and I know it’s unacceptable to all 4 million Oklahomans.”

Supporters say these private insurance companies have more experience in coordinating care with different providers, and they’ll have more flexibility in how they spend their money.

The agency that manages Medicaid, the Oklahoma Health Care Authority, held a briefing with reporters on Friday. During that briefing, Oklahoma Deputy Medicaid Director Traylor Rains gave some examples of that flexibility.

“There’s a lot of federal regulations that kind of hamstring our abilities to do certain things, like incentives,” he said. “To give certain incentives to members to join a gym, for example, or in the middle of the summer, if the AC goes out to buy a window unit to prevent someone that has a heart condition from going to the E.R. So these are things that a managed care plan can do that we can’t.”

Opponents are concerned the program was designed hastily, that it will reduce health access for low-income Oklahomans instead of improving it, that the $2 billion in contracts faced no legislative oversight, and that Oklahoma’s past attempts to implement full managed care failed miserably.

Oklahoma used managed care in the past, abandoning the model in 2003 after too many insurance companies dropped out of the program. Officials have considered resuming the policy for several years. Governor Stitt showed some interest, but it really took off last year.

“With medicaid expansion now in our Constitution, this is the perfect opportunity to re-imagine health care delivery in Oklahoma,” Stitt said during the State of the State.

He’s referring to the new policy Oklahoma voters adopted this summer. They opted into an Affordable Care Act program that has been available to the state for a decade, which expands Medicaid coverage to more low-income working adults. The governor’s office and Legislature had previously opted out of the program, arguing it was too expensive, but voters placed it into the constitution when they passed a state question in June 2020.

Those 200,000 expected new enrollees and most of the rest of the Medicaid population will be using one of the four health insurance companies.

Just about every health industry group — including the Oklahoma Hospital Association, the Oklahoma State Medical Association — have issued statements condemning the program. The latter issued a release last week, stating it intended to file a lawsuit with the Oklahoma Supreme Court to block the policy until lawmakers can weigh in. The association was joined by several others:

Several members of the Legislature have spoken out against the policy. Dozens of Republicans issued a joint release in December decrying it, saying that its implementation would be a costly disaster.

Current senator and former Senate Health Chairman Rob Standridge has been a vocal opponent. He expressed many concerns. The Oklahoma Health Care Authority faces a cap on its administrative spending at 5 percent, he said. The companies’ cap is 15 percent. He also raised the concern that the Legislature had no say in the bidding process.

“This may be the biggest contract ever contemplated by the state of Oklahoma, and we’re going to do that without legislative approval,” he said. “That defies all logic, in my opinion.”

Lawmakers have also raised concerns about the $50 million in state funding it would take to even launch the program, among other worries.

Note: This story is one of a series looking at Oklahoma’s managed care proposal.