Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter begins closing statements during the opioid trial at the Cleveland County Courthouse in Norman, Okla. on Monday, July 15, 2019.

Chris Landsberger / The Oklahoman

Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter begins closing statements during the opioid trial at the Cleveland County Courthouse in Norman, Okla. on Monday, July 15, 2019.

Chris Landsberger / The Oklahoman

Chris Landsberger / Oklahoman

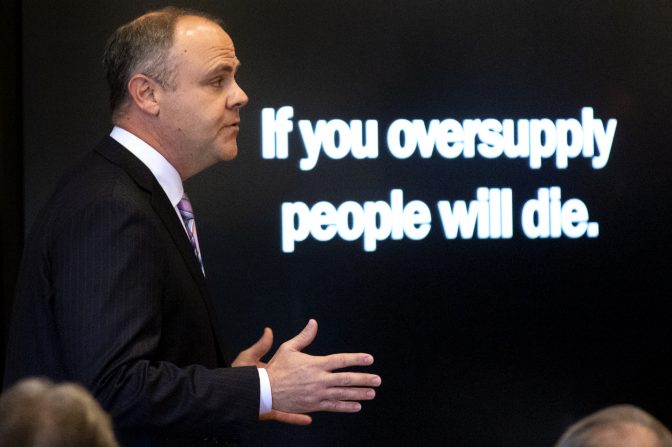

State’s attorney Brad Beckworth presents information in the opening statements during the Oklahoma v. Purdue Pharma opioid trial at the Cleveland County Courthouse in Norman, Okla. on Tuesday, May 28, 2019. The proceeding is the first public trial to emerge from roughly 2,000 U.S. lawsuits aimed at holding drug companies accountable for the nation’s opioid crisis.

The legal fight over who is responsible, and who should pay for the national opioid crisis that has killed thousands of Americans will likely take years.

In 2017 alone, more than 48,000 Americans fatally overdosed on opioids, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — accounting for more than two-thirds of all drug overdose deaths nationwide that year.

States, tribes, and municipalities across the nation, have joined a 2,500 case multidistrict litigation. Oklahoma’s leaders took a different tactic. Rather than join the larger federal litigation state Attorney General Mike Hunter chose to take opioid manufacturers and more recently distributors to state court.

As a result, the state is entitled to $829 million from settlements with drug companies or court orders. But so far, none of the money has been spent on opioid addiction treatment. Here’s where the money stands for each company or group.

At the conclusion of a seven week-long trial in Norman, Oklahoma District Judge Thad Balkman found Johnson & Johnson liable for helping fuel the state’s opioid crisis and ordered the company to pay $572 million to help meet health and addiction costs incurred by the state. The amount was based on what state lawyers claimed one year of abating the opioid crisis in Oklahoma would cost.

But in a motion filed with the court, lawyers for Johnson & Johnson pointed out that the judge inadvertently added three zeros in one portion of the calculation. They said one category, which would fund neonatal abstinence syndrome treatment evaluation standards, should be $107,600 not the $107.6 million in the judge’s August decision. At a hearing in October, the judge agreed.

Balkman decreased the amount the company owed the state to a one-time payment of $465 million.

His decision could mean the judgment amount will be cut, but the total amount that Johnson & Johnson will ultimately have to pay Oklahoma is unclear.

That’s because both sides have appealed.

Attorneys for the state argue that the judge should maintain jurisdiction over the case and annually review whether the public nuisance has been resolved. That proposed process could result in additional payments to Oklahoma from Johnson & Johnson that could be in the billions of dollars.

Johnson & Johnson’s defense team focused on the question of whether the specific opioids manufactured by the company could have caused Oklahoma’s high rates of addiction and deaths from overdose.

Johnson & Johnson’s lawyer, Larry Ottaway, argued the company’s opioid products had a smaller market share in the state compared to other pharmaceutical companies, and he stressed that the company made every effort when the drugs were tested to prevent abuse. He also pointed out that the sale of both the raw ingredients and prescription opioids themselves are heavily regulated.

“This is not a free market,” he said. “The supply is regulated by the government.”

Ottaway maintained the company was addressing the desperate medical need of people suffering from debilitating, chronic pain — using medicines regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and the Drug Enforcement Administration. Even the state of Oklahoma purchases these drugs, for use in health care services.

The Oklahoma Supreme Court will hear the appeals beginning in spring.

The court could overturn Balkman’s order and find in favor of the company, or if they side with the state, the amount the company owes could change significantly, but the state won’t be paid until litigation of the case has ceased.

Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter filed suit in 2017, alleging Purdue helped ignite the opioid crisis with aggressive marketing of the blockbuster drug OxyContin and deceptive claims that downplayed the dangers of addiction.

The drug giant settled with the state in March, about two months before the trial began. The drug giant agreed to pay the state $270 million and Hunter agreed unilaterally to a plan for how the money would be spent.

The vast majority of the settlement about $200 million would pay for an addiction research and treatment center at Oklahoma State University in Tulsa.

Oklahoma lawmakers were furious.

“Rose petals were not strewn in my path,” Hunter acknowledged in a speech before the Bipartisan Policy Council in Washington DC in May. “There was a great consternation with me going around the appropriations process.”

State lawmakers quickly changed the law so that any future settlements would go to the state treasury, to be allocated by the legislature.

The settlement also included $20 million for medicines to be used by patients in the center, $12.5 million for counties and municipalities in Oklahoma and $60 million for legal fees.

Purdue Pharma has paid the state $102.5 million, and the Sackler family has made it’s first of five $15 million payments, but that money isn’t being spent. OSU officials say that a board is still being formed to head the organization, with no start date in place.

Meanwhile, the federal government is seeking its slice of the settlement. In a June letter, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) stated that because the state relied on decades of Medicaid claims data to help determine the amount of opioid-related damages, the agency is entitled to its share.

Initial documents sent from the state to CMS and obtained by StateImpact estimate that the federal government could be entitled to around $60 million of the Purdue settlement. The state and CMS are continuing discussions.

Hunter’s office claims that the $12.5 million designated for cities and counties will be distributed at a later date after a board has been formed to allocate it.

The Israel-based pharmaceutical company became the second to settle, just days before they were headed to trial. Teva agreed to an $85 million settlement, leaving Johnson & Johnson as the sole defendant.

Lawyers hired by the state were entitled to $13 million under the terms of their agreement with Hunter’s office.

Because Teva settled after legislators hurriedly changed the law, the remaining $72 million Teva settlement is in the state treasury, waiting to be allocated by lawmakers.

Jackie Fortier / StateImpact

Narcan, also known as Naloxone is an opiate overdose antidote.

In January 2020, Endo International agreed to an $8.75 million settlement to keep them out of court in the state. Oklahoma had threatened litigation, claiming the drugmaker contributed to the opioid crisis by inappropriately marketing its addictive painkillers.

Hunter’s office says the Endo settlement will join the Teva settlement in the state treasury after lawyer’s fees have been deducted.

In January 2020, Hunter announced Oklahoma’s lawsuit suing some of the nation’s largest pharmaceutical drug distributors. The state contends that some of the industry’s titans—McKesson, Cardinal Health, and AmerisourceBergen—helped fuel that state’s opioid crisis by ignoring red flags.

Hunter said at a press conference that the companies are liable for an unspecified amount of damages because they should have known big orders of pills were being diverted and abused.

“These companies made billions of dollars by supplying massive and unjustifiable quantities of opioids leading to oversupply diversion addiction and overdose deaths,” he said.

“They have blood on their hands,” Hunter added.

The drug distributors have already paid hundreds of millions in settlements to counties and states so far.

Oklahoma is seeking a jury trial, with no trial date set.