A sign is seen outside of 50 Penn Place in Oklahoma City where Epic Charter Schools leases 40,000 square feet for administrative use.

Whitney Bryen/Oklahoma Watch

A sign is seen outside of 50 Penn Place in Oklahoma City where Epic Charter Schools leases 40,000 square feet for administrative use.

Whitney Bryen/Oklahoma Watch

Oklahoma investigators believe Epic Charter Schools embezzled money by inflating its enrollment with homeschool and private school students. Because of the state’s dedication to privacy, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Joy Hofmeister says the alleged abuse would not have been preventable under current state law.

The Enrollment Loophole

Virtual charter schools are taxpayer-funded public schools. Like traditional public schools, they are free to families and receive funding from the state based on student enrollment. Unlike traditional public schools, they are run by private companies or non-profits, and student instruction and coursework happen online instead of in-person.

With over 20,000 students on the books last year, Epic is the largest virtual charter school in Oklahoma, and it appears to be exploiting a loophole in state law.

All virtual charters are under the purview of a separate agency, the Statewide Virtual Charter School Board, but verifying enrollment falls to the State Dept. of Education.

The education department has the data to easily keeps tabs on kids enrolled in public schools, including Epic, but it cannot track private or homeschooled students because they aren’t required to register with the state government. That makes it nearly impossible to weed out these so-called “ghost students” who are dually or falsely enrolled in homeschool or private school as well as a virtual charter school during routine audits.

“We do not have at the state level a list of homeschool students or private school students,” said Hofmeister. “So, if indeed what is being alleged and investigated is true, there isn’t a mechanism to be able to cross check-information and certify that what they report is accurate.”

One Homeschool Mom’s Story

Epic Charter Schools touts many benefits, but one reason for its popularity is financial incentives.

“For the homeschool community, the appeal has been the money,” explained Teresa Burnett, a homeschool parent from Shawnee.

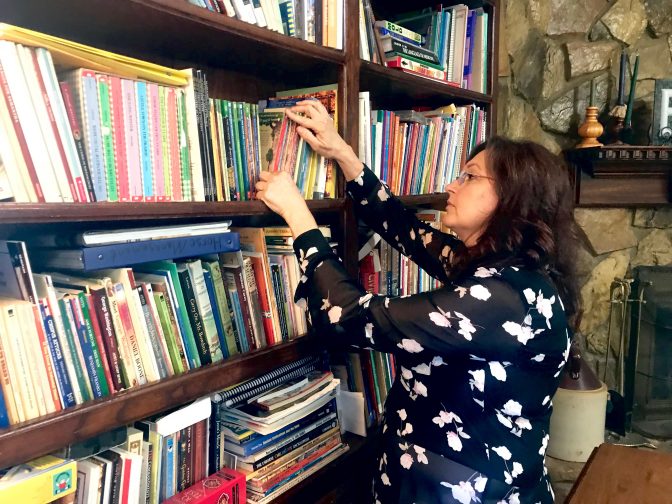

Teresa Burnett thumbs through a bookshelf in her living room that she uses to home educate on July 18, 2019.

Epic teachers get bonuses for recruiting students and families receive up to one thousand dollars per child. That money is part of what Epic calls its “Learning Fund,” which can be used to purchase extra products and courses.

Burnett regularly joins with other homeschool families in a co-op to do lessons and go on outings. While she has stuck exclusively with home education, many of those in the co-op she participated in last year have joined Epic.

“By the time we got to October, November, I’m going to estimate approximately 50 percent of the families had all enrolled in Epic,” Burnett recalled. “They were still participating in the co-op and still enrolled at Epic. These moms were being told that they basically can have the best of both worlds. We can home educate, and then we get to also take advantage of the perks that Epic will provide. ‘Perks’ being the financial perks.”

State law enforcement describes these kids as “ghost students”— homeschool and private school students that are also enrolled at Epic but receive little to no instruction from the school. Epic’s founders allegedly used them to embezzle millions of taxpayer dollars.

Lawmakers Weigh In

At least one state senator, Republican Ron Sharp, thinks the legislature should have done something to prevent Epic’s purported abuses.

“The state legislature has basically allowed for unlimited and unrestricted enrollment in your virtual charters without proper verification,” said Sharp, who is a former public school teacher and an outspoken critic of Epic Charter Schools. “The problem is all efforts of which to provide oversight have been met with resistance.”

Sen. Ron Sharp voiced his concerns about Epic Charter Schools in his office on July 17, 2019.

Lawmakers did tighten financial reporting requirements for virtual charter schools this year, and in 2018, they passed a law requiring virtual charters to implement attendance policies. Sharp thinks lawmakers could have done more sooner. His fellow Republican, Sen. Gary Stanislawski, however, disagrees.

Stanislawski pointed out that former Governor Mary Fallin directed the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation to investigate Epic in 2013, and no charges were filed.

“There was nothing that came out of that investigation whatsoever that told us that we needed to create any type of new policy,” Stanislawski said.

Stanislawski, who chairs the Senate Education Committee and architected the 2012 law allowing virtual charter schools to begin operating in the state, says he’s open to new regulations depending on how the current investigations into Epic play out.

“I think it is important we allow the investigation to conclude before we try to figure out what we need to do,” Stanislawski said.

Oklahoma would not be the first state to pass more virtual charter school regulations in response to a scandal. In Indiana, for example, a similar enrollment controversy led to a new law requiring virtual charters to drop students who fail to log into classes for too long. But even if the general appetite for regulation increases, closing Oklahoma’s enrollment loophole by creating a roster of homeschool and private school students may not be politically feasible.

“Our state is not one that wants to intrude on personal information of family members who are choosing not to be a part of public schools,” Hofmeister said.

Even Sen. Sharp admitted he could not support such a law and survive reelection.