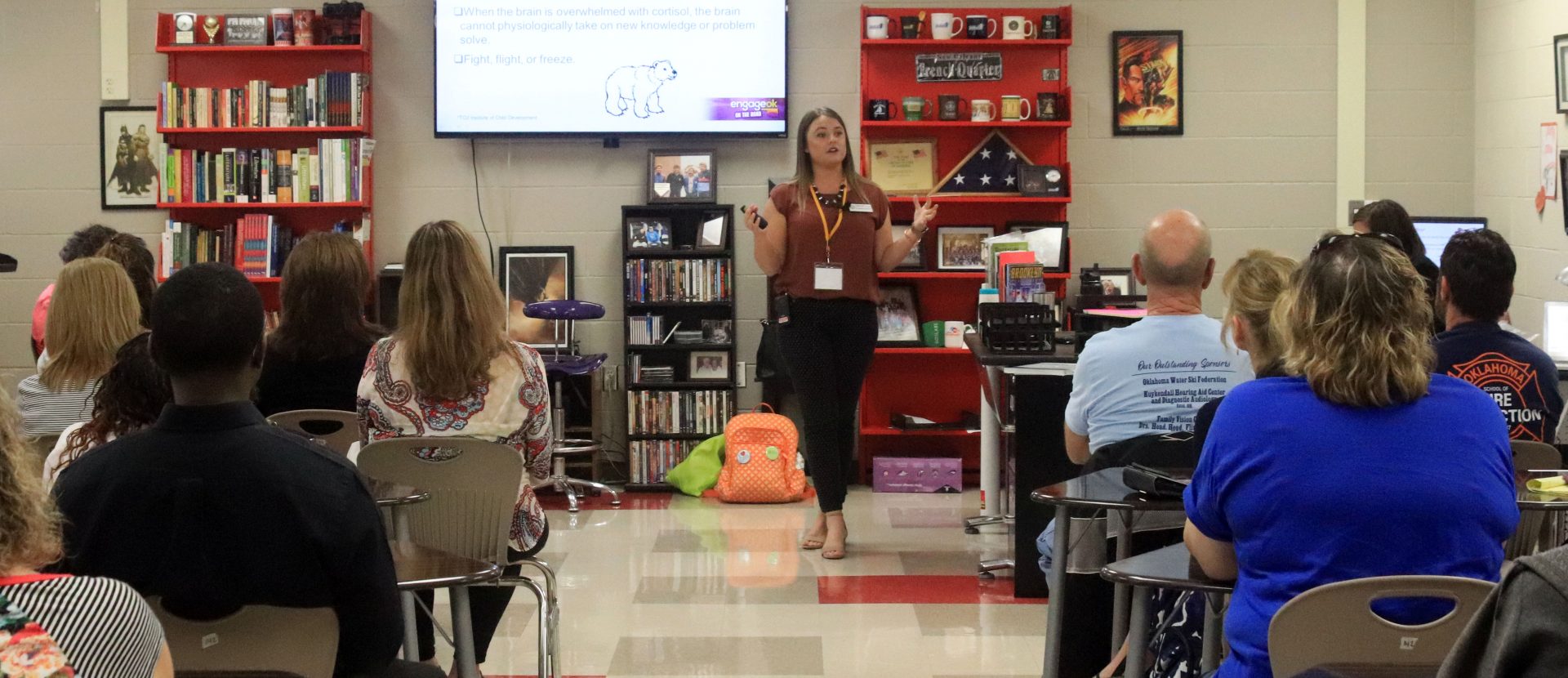

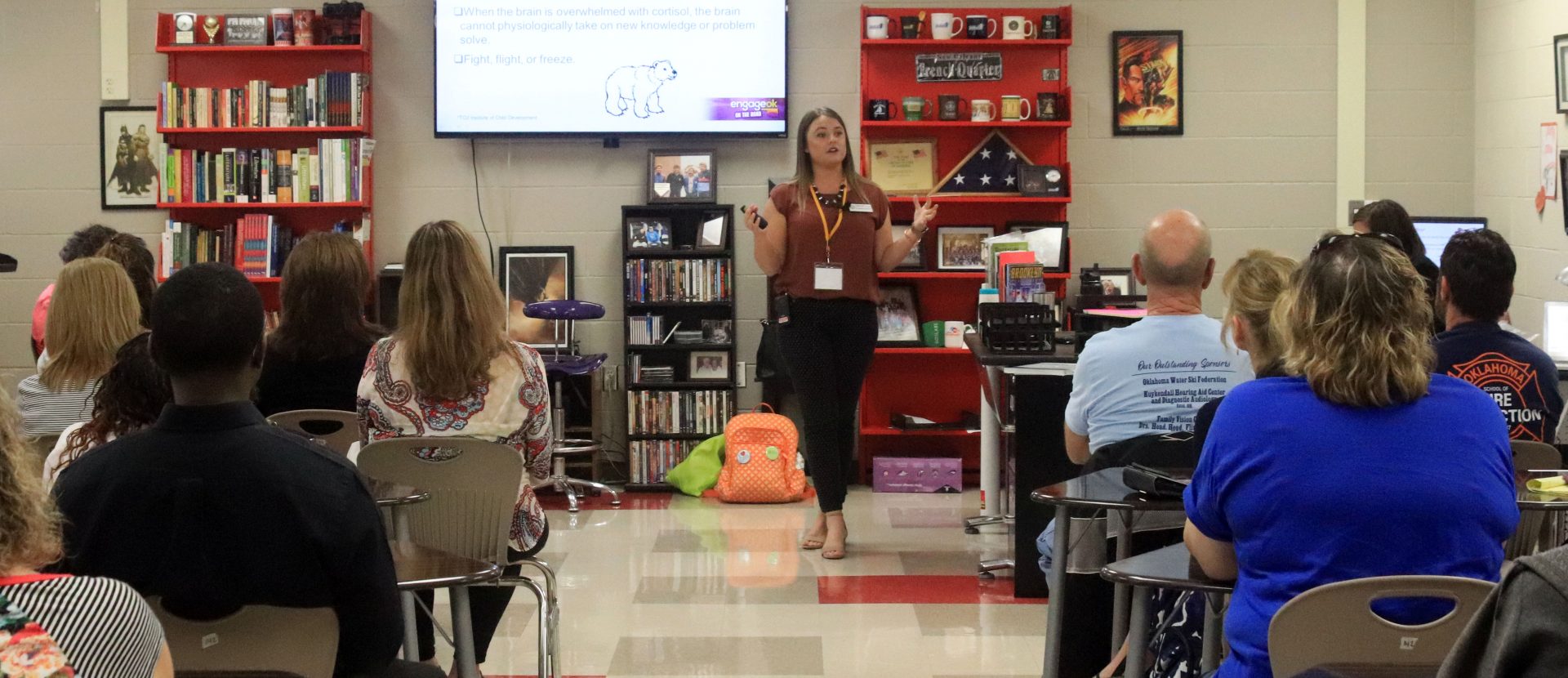

Oklahoma teachers learn about student trauma at a training session at Duncan High School.

Emily Wendler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Oklahoma teachers learn about student trauma at a training session at Duncan High School.

Emily Wendler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Emily Wendler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Kristin Atchley, the Executive Director of Counseling for the State Department of Education, educates teachers about student trauma.

Kristin Atchley, the Executive Director of Counseling for the State Department of Education said it’s standard practice for Oklahoma school teachers to yell at kids who are causing trouble, send them to the principal’s office, or tell them to put their head down without much regard for what might be driving their poor behavior.

Now she’s trying to change that.

“We didn’t know what we didn’t know,” she told a group of teachers in a training session at Duncan High School. “Well now we know it, and we can’t do it.”

Atchley has traveled around the state for the last seven months sharing research with teachers about student trauma, and how that trauma affects kids’ brains and behavior. She’s telling teachers that simply disciplining a child who’s experienced trauma can do more harm than good.

Atchley’s goal for these training sessions is to help teachers make small tweaks in the way they react to kids’ poor behavior, which she said can add up to big, positive changes.

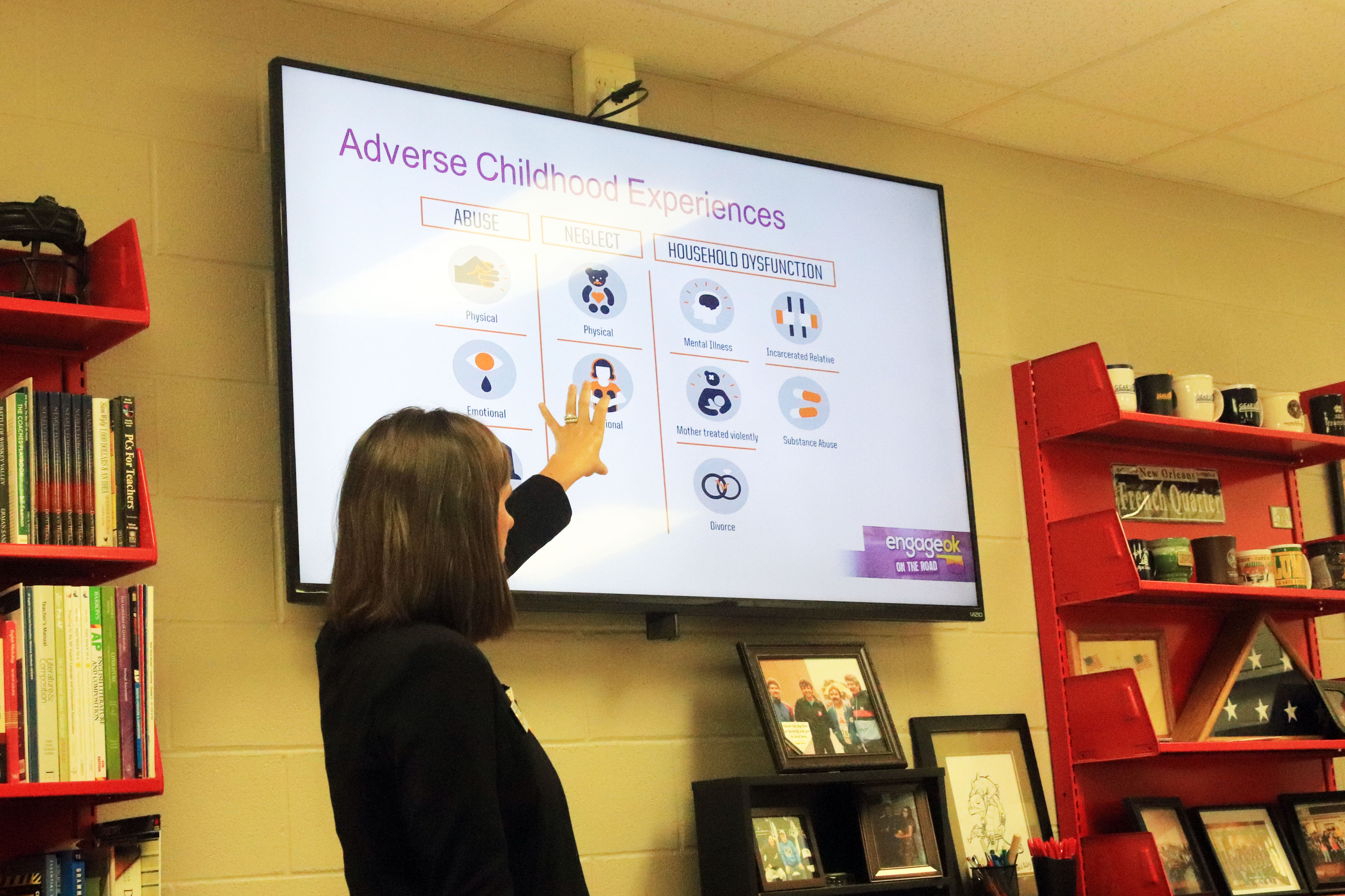

Trauma can mean many different things, but the kinds of trauma Atchley is focusing on are called Adverse Childhood Experiences — often referred to as ACEs.

ACEs are a list of 10 types of trauma that children experience, including physical and emotional neglect, physical and emotional abuse, and household drug and alcohol abuse.

In Oklahoma, 54 percent of children reported at least one Adverse Childhood Experience —the second highest rate in the country.

Atchley said researchers and schools are learning more about how trauma affects a child’s developing brain.

“Kids who experience trauma learn to respond to that trauma with survival skills instead of reasoning skills, which can look like bad behavior and poor decision making to teachers and school administrators,” she said.

Atchley said disciplining or yelling at a traumatized child can re-traumatize them, making it difficult for them to calm down and continue learning. She’s teaching educators alternative ways of dealing with students who are acting out.

Emily Wendler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Meagan Bryant, Mid Del Public Schools’ Coordinator of Counseling, is training the district staff to be more trauma-informed.

Officials at the Mid-Del Public Schools district have taken Atchley’s training and are running with it.

Meagan Bryant, Mid-Del’s Coordinator of Counseling who’s leading the change, calls it a “shift in mindset,” and said the first step is to educate staff about student trauma.

She said support staff, including janitors and cafeteria workers, received trauma training while schools were closed during the nine-day teacher walkout. Bryant also incorporated lessons for teachers in their mandatory professional development sessions before school started.

Bryant’s second step to becoming a more trauma-informed district is to give staff new tools for dealing with students who are acting out, which she said is an ongoing process.

“They can have a regulation station — an area where the kids can go and cool down,” she said. Another idea is for school staff to help students practice breathing techniques when their emotions get out of control.

Sometimes the strategy she encourages teachers to adopt is to just be more empathetic towards students. But she tells them that having this kind of empathy doesn’t mean they’re letting kids off the hook for their actions.

Instead, she said the idea is to make sure students who are struggling with trauma feel safe and calm during the discipline process so that they ultimately stay engaged in school.

Research shows that students who feel safe in school and emotionally supported by their teachers do better academically.

Atchley said schools are catching on to this research — and want to know more.

“I can’t even keep up with the requests coming to my office, for me to come out and speak on this topic,” she said.

She said every time she puts on a training session about student trauma the room is packed, and when it’s over, teachers thank her and say, “this information just makes sense.”