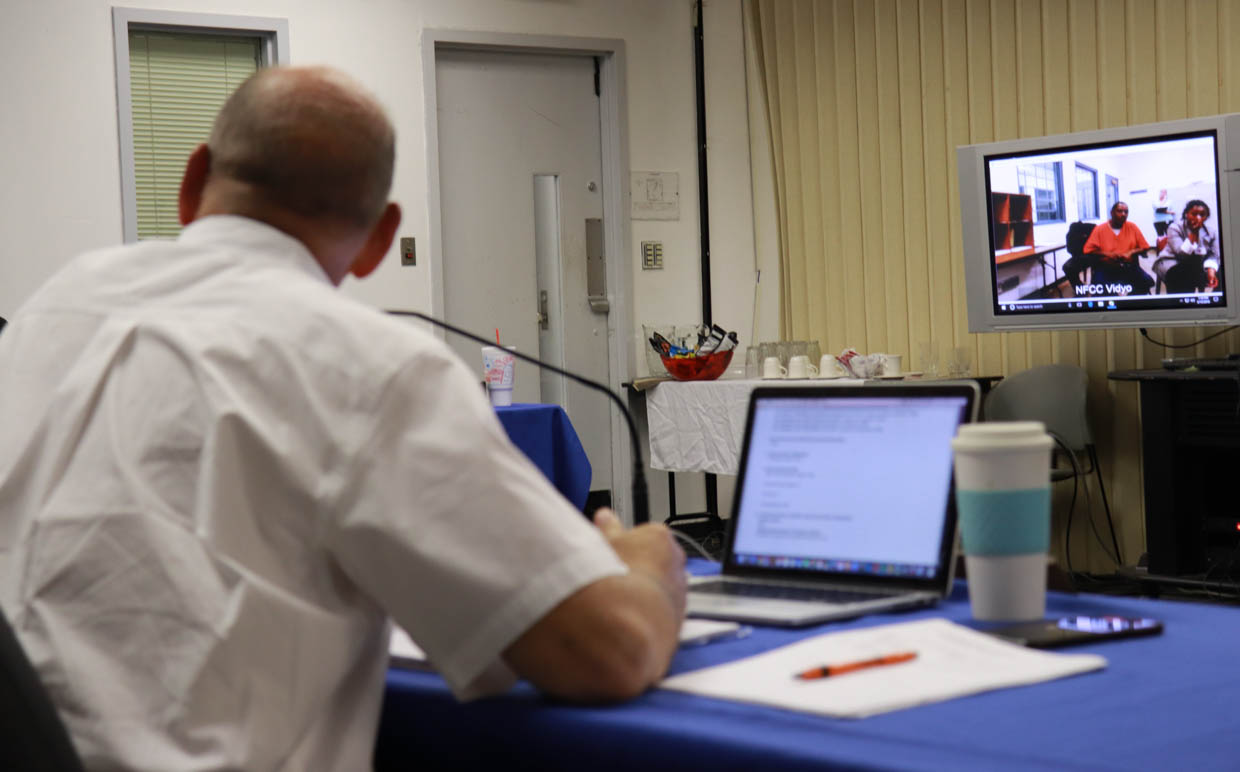

Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board interviews parole candidate.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

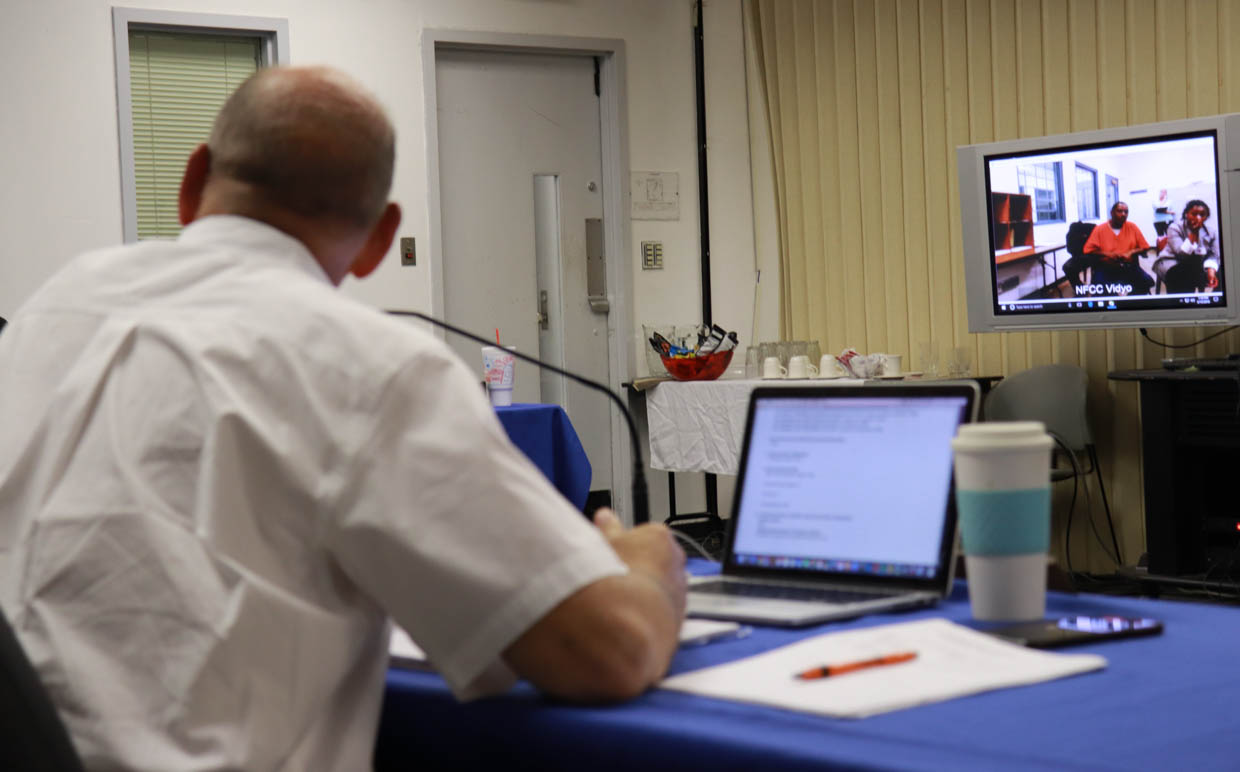

Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board interviews parole candidate.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

Frank McCarrell and his grandson Roman.

Baby Roman is just waking up from his afternoon nap and now he’s looking for a toy. His grandfather, Frank McCarrell, is trying to distract him from the house’s décor with a bottle of milk.

“He don’t usually be asleep this time,” said McCarrell, who just finished his workday to babysit for his daughter. “When I come home … usually he’s up and raring to go. Huh? You be running Papa around?

This is the highlight of McCarrell’s day. He goes to his job as a machine operator four days a week and then comes directly home to hang out with Roman. But, this routine is relatively new for McCarrell. He’s beginning his third year on parole for a drug conviction.

Years ago, McCarrell had finished serving 10 years for armed robbery when he was arrested again while carrying 1.4 grams of crack cocaine. McCarrell says he was using and selling the drug. His new arrest led to a 40-year prison sentence, which he thinks was an unfair punishment for not taking a plea deal.

McCarrell served about 12 years of the sentence before he was paroled — But most Oklahoma prisoners are not like Frank McCarrell.

Unlike some surrounding states, Oklahoma’s inmates can decide whether or not they want to be considered for parole. Roughly two out of three parole-eligible inmates choose not to go to their parole hearings, effectively disqualifying them for early release.

In late 2016, the state started counting how many inmates opted out. In one year 5,225 of the state’s 7,921 parole-eligible inmates chose not to go to their parole hearings.

State officials say this contributes to prison overcrowding and hurts inmates’ chances to avoid new convictions after they are released.

When McCarrell was imprisoned, he saw a lot of inmates opt out of their hearings. “I would ask some of them why,” he said. “And their reasoning is they don’t want to have to deal with the parole, the parole officers and this and that.”

Now, standing outside a probation and parole office in downtown Oklahoma City after a check-in with his parole officer, McCarrell understands why.

Most parolees have to agree to certain rules as a condition of their release. McCarrell, for example, has to meet his parole officer every couple of months, undergo random drug tests and he has to block out time for mandatory counseling.

McCarrell says it’s not too bad, but he hates checking in. “Because it’s always something new,” he said.

It’s always a hassle, he said. After two years on parole, Officers still question whether he’s staying out of trouble, which wears him down.

Quinton Chandler / StateImpact Oklahoma

DeLynn Fudge, executive director of the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board.

Delynn Fudge, the executive director of the state Pardon and Parole Board, is familiar with McCarrell’s frustrations. She said many offenders don’t want to deal with parole requirements. But, she said, the rules are important.

Some parolees could be required to have a breathalyzer installed in their car or wear an ankle monitor. Fudge says others might be required to get substance abuse treatment. “I think our top one is mental health, personal counseling,” she said.

Inmates released without these requirements are more likely to come back to prison,” Fudge said, “because there’s no one that is going to … bring them in and say, ‘Here’s some services that are available to you,’ in their community.”

Focus groups with Oklahoma prison inmates conducted in 2010 by the Council of State Governments confirmed many inmates would rather stay in prison than deal with parole restrictions. The inmates said they could even finish their sentences faster in prison if they get time off for good behavior.

Fudge says this is a problem.

“We want them to have the support systems, so that’s No. 1,” Fudge said. “Two, it’s an overcrowding issue. If they’re waiving parole, then they’re staying in prison.”

State officials considered new legislation that would prevent inmates from waiving parole reviews this year, but the idea was dismissed. One reason is that such a large increase in parole reviews would likely overwhelm the Pardon and Parole Board.

Frank McCarrell says he’s following the rules. But now, his new parole officer is telling him something he doesn’t want to hear.

When McCarrell accepted his parole terms more than two years ago, he agreed to move into a halfway house for a year. But, he said, “the halfway house was trashed out. It was just filthy and there were no professional people there, you know, counselors or anyone, sober living, nothing.”

McCarrell says he didn’t want to live there. He complained and said the Probation and Parole office, at first, compromised and said he didn’t have to move in.

Now, McCarrell says he’s been instructed to make good on his original agreement. He says he’d rather go back to prison.

“You know it sounds silly in a way,” McCarrell admits. “But it’s just a fact. You know, for me that’s a fact. I’d rather do that than deal with that. I just would. I can’t explain it.”