New Law Gives Oklahoma More Responsibility In Finding And Fixing Failing Schools

-

Emily Wendler

Oklahoma State Department of Education

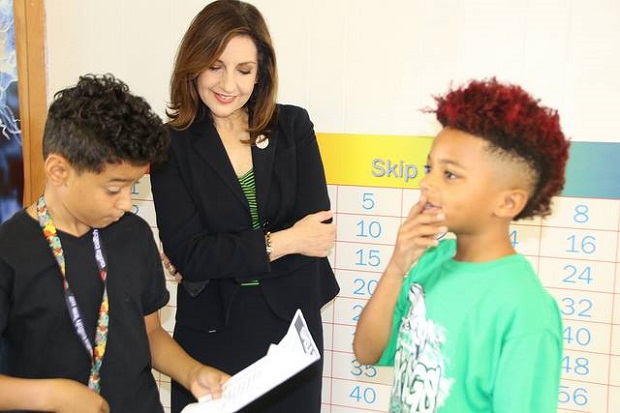

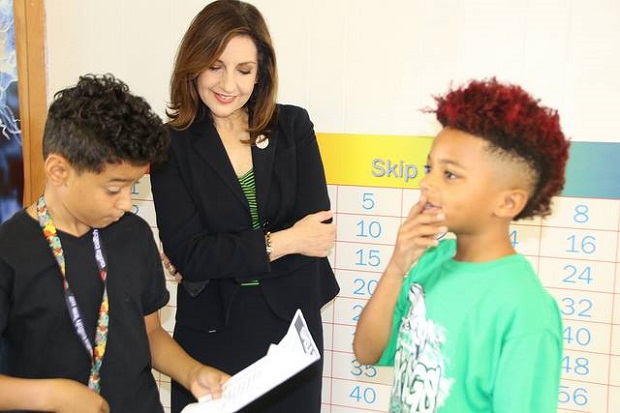

State Superintendent of Public Instruction Joy Hofmeister

Many people say the former massive federal education law, No Child Left Behind, was a failure. When President George W. Bush signed it in 2002, he set a huge goal for the country: Every child would meet the proficiency standard on state tests by 2014.

But, that never happened.

In order to reach this ambitious goal, the law increased the federal government’s role in state education systems, particularly in improving their worst-performing schools. To be eligible for certain federal dollars, states had to abide by strict guidelines of the law — which was, some say, a big reason the law didn’t achieve more.

For example: In 2010, six Tulsa Public Schools received a total of $22 million in School Improvement Grants. These federally funded grants were a main tenant of NCLB and were given to low-performing schools to help them progress.

Keith Ballard, Tulsa Public Schools’ superintendent at the time, says the grants were helpful, but they didn’t do as much as he hoped, especially given the amount of money that was spent. One part of the problem, he says, is the federal guidelines for spending the money were too rigid.

“I think that we could have made better use of the dollars, and probably done better, had we been more in charge of the guidelines and decision-making,” Ballard says.

Failing, flexibility

Now, a new federal education law — the Every Student Succeeds Act — is giving states the ability to write their own plans for improving academic outcomes. Oklahoma’s State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Joy Hofmeister, says this is a big change.

“We don’t have a prescriptive federally-defined approach on who is going to need support and what that support has to look like,” she says.

Oklahoma submitted its plan to the U.S. Department of Education on Sept. 18. Individual schools will have a lot more flexibility in how they use federal dollars to improve failing schools moving forward, Hofmeister says.

“The shift for decision making is going to be at the state level and then [state education officials] are shifting some of that responsibility to the local communities,” she says.

Now, when a school is identified as failing, local leaders will be in the driver’s seat, crafting an evidence-based plan for improvement. Hofmeister says her department will be very involved in that process.

State school support officers have already tried some of the strategies laid out in the new plan, and have seen positive results, she says.

New report cards

Another big change in the law is how Oklahoma and other states will identify failing schools.

Under No Child Left Behind, the U.S. Department of Education forced states to create school grading systems using narrow federal guidelines. Hofmeister says this system was flawed, and caused Oklahoma to flag hundreds of schools as failing, that weren’t.

State education officials used the flexibility provided under ESSA to create a new A-F Report Card — one Hofmeister thinks is more accurate, and won’t divert precious time and resources away from schools that really need it

“Our goal is to do intensive work to those truly at the bottom, where they are failing students,” she says. “Instead of spreading the same amount of money across 300 schools, we’re now focusing on maybe 90.”

New responsibility

Once the U.S. Department of Education approves Oklahoma’s plan — and Hofmeister expects it will — the state agency will be in charge of making sure all of this works.

“We have to be able to step up and do what we’ve asked for,” she says.

For some, this is scary.

Congress passed No Child Left Behind 15 years ago for a reason: Poor accountability lead to some lousy schools and kids suffered. Hofmeister says that’s changed — and Oklahoma is ready.

She’s confident this time around, things will be better: Oklahomans had more control over their new blueprint for improving education, and they don’t have to follow a generic plan handed down from Washington, D.C.

“We can move the needle for kids and create the kind of public education system that they deserve,” Hofmeister says.