A mountain of waste rock outside a zinc concentrator near the Eagle-Picher plant near Cardin, Okla., in 1943. Production at the Tri-State Mining District peaked in the 1920s and largely stopped by 1970.

Fritz Henle / Library of Congress

A mountain of waste rock outside a zinc concentrator near the Eagle-Picher plant near Cardin, Okla., in 1943. Production at the Tri-State Mining District peaked in the 1920s and largely stopped by 1970.

Fritz Henle / Library of Congress

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

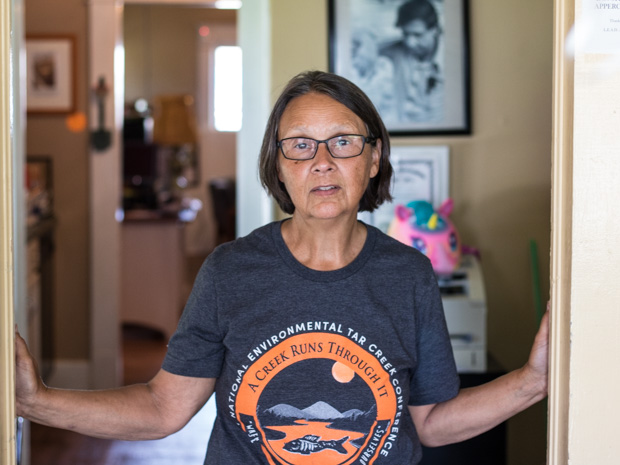

Rebecca Jim, executive director of the L.E.A.D Agency, at the nonprofit's headquarters in Miami, Okla.

Newly minted U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt spent his first months on the job steering the agency away from climate change to focus, in part, on cleaning up contaminated sites around the country.

The former Oklahoma attorney general has directed a task force to create a top-10 list of locations that need aggressive attention — welcome news at Superfund sites like Tar Creek in the northeastern corner of the state.

The spot where Kansas, Missouri and Oklahoma meet was once one of the world’s largest sources of lead and zinc. About half of the lead and zinc the military needed in World War I was produced here, in 300 miles of caverns hollowed out underneath towns like Picher, Cardin and Commerce.

In 1983, Tar Creek became one of the first sites added to EPA’s Superfund list. The law helps identify sites contaminated by dangerous substances, prevents hazards and makes responsible parties pay for cleanup.

Tar Creek is one of the oldest sites on a list of roughly 1,330 Superfund sites across the country. It’s large and has a lot of public health risks. It’s the kind of cleanup EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt is signaling is a priority.

“There are many that have been on that National Priority List for decades, languishing for direction, leadership, answers,” Pruitt told a U.S. House subcommittee in June.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Hills of mining waste known as 'chat' are scattered throughout the abandoned lead and zinc mine at the Tar Creek Superfund.

Mining in the tri-state district peaked in the 1920s and stopped by the ’70s. The miners left town; Cave-ins, dangerous dust and caustic water remained. Blood tests showed elevated levels of lead in more than 40 percent of children in some communities.

Most residents took buyouts to leave the former mining towns, which are largely abandoned by anyone not driving a truck tasked with hauling off hills of gravelly waste called chat that fill the horizon like moon-colored dunes.

“We’re averaging an almost 3,000 tons a day of of chat to the repository,” says Craig Kreman, assistant environmental director for the Quapaw tribe.

Fritz Henle / Library of Congress

A mountain of waste rock outside a zinc concentrator near the Eagle-Picher plant near Cardin, Okla., in 1943. Production at the Tri-State Mining District peaked in the 1920s and largely stopped by 1970.

The chat piles are just one part of the problem. Much of the ore was buried below the water table. When the companies left and stopped pumping the mines dry, the caverns filled up. Water carrying cadmium, lead and other toxic metals bubbles to the surface into Tar Creek and downstream into a critical watershed.

The EPA didn’t respond to interview requests. In the testimony on Capitol Hill, representatives pressed Pruitt on how he could champion the Superfund program while simultaneously supporting a budget plan from President Trump that slashes the program’s funding by nearly one-third.

“It’s more about decision-making, leadership and management than money, presently,” he said. Later, Pruitt told the committee he’d push for more funding if he felt it were needed.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

A worker brushes dusty mine waste off a truck before it exits the contaminated site.

Katherine Probst, an independent consultant who has spent 20 years researching and evaluating EPA’s Superfund program, says poor funding has plagued the program for decades.

“They don’t have the money to clean up an average Superfund site in most states,” she says. “They just don’t have $25 million to clean up a site.”

Superfund was initially funded by a trust fed by taxes on crude oil, chemicals and environmental taxes levied on corporations. Those taxes expired in 1995 and were not reauthorized. The money now comes by way of congressional appropriations. Research from Probst and the U.S. Government Accountability Office shows funding for Superfund has declined for nearly two decades — under Republican and Democratic administrations.

Probst says Superfund sites would benefit from clearing bureaucratic red tape, which Pruitt pledges to do. Technical problems are stalling progress at some sites. Others are delayed by foot-dragging by companies deemed responsible for contamination. Other roadblocks are unknown due to poor data about the sites and the health hazards they pose.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

A truck filled with chat transports mining waste to a nearby repository near Picher, Okla. Some of it is processed and reused for asphalt, while the most contaminated chat is taken to specially designed landfills for long-term storage. More than 180 truckloads carrying 3,000 tons of waste are transported daily.

Rebecca Jim, the executive director for L.E.A.D. Agency, says the government’s attention to Superfund faded alongside the tax money.

“Superfund is broke,” she says.

Jim founded the nonprofit in the mid-’90s to organize and amplify local residents’ concerns about the Tar Creek contamination and cleanup. The group’s headquarters in nearby Miami has become an information hub about the contaminated site and a community center for local youth.

Jim would like Superfund’s stream of tax money restored, but acknowledges that’s likely a pipe dream.

“You get a good start in trying to do the clean up, but you just do a little at a time — that’s all you can do,” she says.

In 2012, the EPA signed an agreement for the Quapaw to lead and manage the Tar Creek project — the first tribal-led cleanup of a federal Superfund site. Earlier this year, the agency awarded the tribe $4.8 million to clean up soil from contaminated tribal lands.

Jim says the tribal management is a positive development for Tar Creek.

“We’ve got some real hope to start restoring some larger pieces of land, but it costs money,” she says.

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

Quapaw Assistant Environmental Director Craig Kreman stands in a section of the Tar Creek Superfund site where remediation efforts are nearly complete.

Top EPA officials recently traveled to northeastern Oklahoma for a tour of the Tar Creek Superfund site. Kreman with the Quapaw says the tribe hopes the agency’s visit is a good sign.

“We took them up top a chat pile and they can see, for miles, the effects Tar Creek has had on the environment on the community,” he says.

Kreman says Tar Creek still needs tens of millions in federal money to support a cleanup that will likely continue for decades. If Superfund’s budget is slashed, Tar Creek will compete with others for a smaller slice of funding.

When the top-10 list comes out, Kreman and Jim hope Tar Creek is on it and that the contamination in their community once again is recognized as one of the country’s most polluted places.

“Every single acre is a celebration. Every bit of water that’s cleaned up before it enters Tar Creek, that’s a celebration,” Jim says. “I’m just waiting for the big one. The big joy when it’s done.”