Oklahoma City Drought Problems A Microcosm Of the State’s Water Crisis

-

Logan Layden

Joe Wertz / StateImpact Oklahoma

A grounded boat dock at Canton Lake, where Oklahoma City got billions of gallons of water in early 2013.

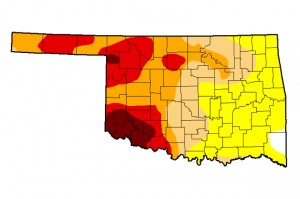

The latest update of the U.S. Drought Monitor shows 98 percent of Oklahoma experiencing at least abnormally dry conditions. As has been the case for the past five years, the worst of the drought is being felt in western Oklahoma, while the abundant waters of the eastern half of the state remain relatively unscathed.

There’s a geographic divide in Oklahoma between those who have plenty of water and those who desperately need it. As State Sen. Josh Brecheen put in during an interview with StateImpact Feb. 9:

“Unfortunately, this has turned into an east versus west debate in our state.”

And in Oklahoma City, it’s easy to see that divide vividly illustrated — not at the capitol building between lawmakers from opposite sides of the state, but between the lakes Oklahoma City residents rely on for water.

A smaller version of what’s happening with the drought statewide can be seen in OKC, where north side residents’ water supply is running low and the south side enjoying plentiful water.

From The Oklahoman‘s Silas Allen:

Take a walk at Lake Overholser or Lake Hefner, and it’s easy to see the toll the multiyear drought has taken on Oklahoma City’s drinking water supply.

Water levels at both north Oklahoma City reservoirs have dropped, leaving the lakes ringed by exposed mud flats that normally would be under water.

Now, city officials are working to move more water from reservoirs in the south, where it is more plentiful, to customers on the north side of the city.

U.S. Drought Monitor

From the Feb. 10 update of the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Residents on the north side aren’t exactly pitted against their south side counterparts, but it’s interesting how closely Oklahoma City’s water problems reflect those of the entire state. Lakes the south relies on — Stanley Draper, with is fed by Lake Atoka and McGee Creek Reservoir in southeast Oklahoma — are doing fine, while the northern lakes — Overholser, Hefner, and Canton — all suffer badly.

For some, a solution to the greater Oklahoma water crisis would include pipelines to move water from where it’s plentiful to where it’s needed. A bill before the legislature now would study that very possibility. But that’s already the plan in Oklahoma City:

They plan to lay a 29-mile pipeline connecting the Lake Stanley Draper treatment plant with a booster station at W Reno Avenue and N Council Road, and another 7 miles of pipeline to connect the booster station with an elevated tank on Cemetery Road south of W Reno Avenue.

That pipeline will improve the ability to move water from where it’s most plentiful to residents in other areas, said Larry Hare, an engineer with the city’s utilities department.

“Trying to get water to everybody is our No. 1 priority,” Hare said.

The paper reports the 29-mile pipeline is about 75 percent complete and has cost nearly $70 million so far. That’s a mere pittance compared to the billion-plus dollar price tag of potential pipelines to carry water hundreds of miles across the state.