c

c / c

c

c / c

Mattgrimm / Flickr

The dam at Lake Eufaula, a reservoir the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built in 1964. Seven reservoirs were built that year, the peak of reservoir construction in Oklahoma.

State officials, meteorologists and climate researchers say Oklahoma’s water needs are going to increase exponentially over the next century. Oklahoma’s population is projected to grow by almost 50 percent by 2075, according to state estimates. But the state isn’t getting any wetter.

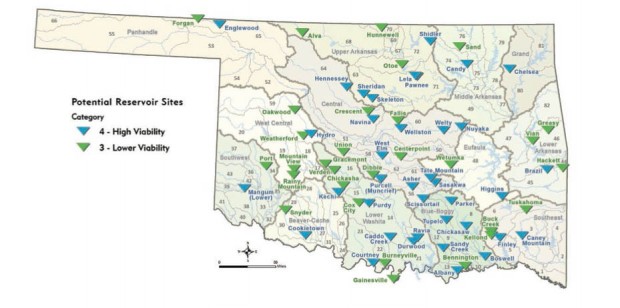

Water authorities in Oklahoma say there’s potential to build 68 new reservoirs. That would be in addition to more than 100 reservoirs built in the state in the last century.

Building lakes in Oklahoma is harder than it’s ever been, however. Here’s why.

New reservoir construction slowed to a trickle after the Water Resource Development Act of 1986 was signed into law. To that point, the federal government could fully pay for dam construction. The 1986 law required cost sharing with states, cities and other local authorities.

Reservoir construction dried up after that, and completely evaporated after 1997, when Oklahoma’s last manmade water supply — the Wes Watkins Reservoir near McLoud — was built.

Reservoirs are expensive to build. According to Ed Rossman with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Tulsa office, one reservoir can cost between $120 million and $190 million. In a time of tight state, local and federal budgets, finding that kind of money won’t be easy.

Source: Oklahoma Water Resources Board

Researchers have identified 68 sites with the most potential for future reservoirs. The locations that make the best reservoir candidates are well-mapped, heavily studied, and have a combination of high need and lowest potential for negative cultural/environmental impact, and predictable construction costs.

But cost is just one concern, says J.D. Strong, director of the state Water Resources Board.

“There are a lot of other things we know now that we didn’t know then,” he says. “There are a lot of new environmental laws and regulations in place. We have the Endangered Species Act, and a lot of endangered species’ problems can be exasperated by reservoir construction.”

The state’s official long-term water plan emphasizes some of those environmental concerns, such as industry’s impact on aquifers, including ones that are the only source of water for streams and wells that are used by rural residents and entire cities.

There’s also a direct human impact that often goes along with damming rivers and building reservoirs. People, their homes and often entire communities, must be moved to make room for manmade lakes.

Sardis Lake — the center of a water rights controversy between Native American Tribes and Oklahoma City — now covers what was once the town of Sardis. Just the town cemetery remains above water, on an island in the middle of the reservoir.

Even the house Will Rogers was born in had to be moved when Lake Oologah’s dam was built.

Rossman says property rights are a much more important consideration in planning reservoir construction than they were in the middle of the 20th century.

“When you do something like this, you’re going to have to acquire all these lands,” Rossman says. “You’re going to have to force these people off their land. And what does that mean to the community? It is a big consideration.”