Philadelphia bets millions that restoring mussels in the Delaware River Basin can improve water quality

-

Catalina Jaramillo/WHYY

Ralph Wilson / AP Photo

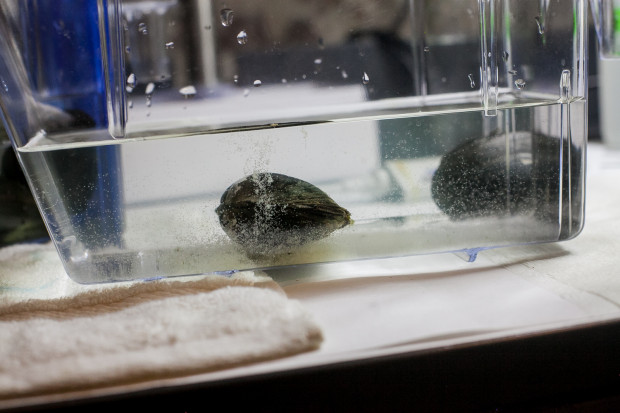

An Alewife Mussel expells its larva, known as Glochidia, which looks like a combination of air bubbles and cloudy milk. (Brad Larrison for WHYY)

Freshwater mussels function as nature’s water treatment plants. Each animal can filter up to 600 gallons of water per month. Working together, they can dramatically clean the water of the rivers they live in.

But the Delaware River Basin is running out of them. And the ones left are not reproducing nearly enough. That’s about to change.

On Tuesday, the City of Philadelphia and five organizations — The Partnership for the Delaware Estuary, Drexel University’s College of Arts and Sciences, The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, Independence Seaport Museum, and Bartram’s Garden — committed to create a large-scale mussel hatchery expected to bring millions of baby mussels back into the river. The facility will be part of a multi-site production and educational initiative called the Aquatic Research and Restoration Center.

The mussel hatchery, which will be located at Bartram’s Garden, already got funding from the state — 7.9 million through the Pennsylvania Infrastructure Investment Authority. The hatchery, which will be owned and operated by the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary, will be the world’s first that is dedicated to restoring mussel beds to promote clean water. Construction could begin next year.

From lab to the river

On a recent Wednesday, seven scientists gathered at a small city-owned hatchery at Fairmount Water Works, around a water tank the size of a shoebox. They stared at a female mussel, waiting for her to give birth.

“Oh! You see that?” said Danielle Kreeger, lead scientist with the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary, when the mussel released what looked like a white cloud of baby mussels. Kreeger has been studying mussels in the Delaware for the last 20 years.

“It’s puffing, it’s pulsing it out in plumes. It’s like contractions when you’re giving birth,” Kreeger said. “She’s basically bearing her babies. Here they come, they’re coming out… wow!!!”

One mussel releases about 100,000 baby larvae, called glochidia, but not all of them will survive. Female mussels carry their larvae for up to nine months. But to thrive, baby mussels, which look like tiny pac-men under a microscope, need a fish. And not just any fish.

The babies of each species of mussel attach to the gills of a specific species of fish. They travel that way for a couple of weeks, until they’re big enough to go through metamorphosis and form organs and a shell, and drop off into the river bed.

A group of year old mussels that were grown in the team’s lab inside the Philadelphia Water Works Mussel Hatchery. (Brad Larrison for WHYY)

If everything goes well in the lab, in less than a year these mussels will be in the Delaware River basin, cleaning the water we drink every day. They will be joined by plenty of mussels in the coming years as the city’s research and restoration center, a scaled-up version of the Fairmount exhibition lab, gets up and running.

Kreeger says freshwater mussels are underappreciated.

“Everyone loves oysters, you know, we eat them. But freshwater mussels are like the ultimate underdogs,” she said.

Kreeger said freshwater mussels can’t be eaten by humans because they have parasites and toxins that would be harmful. But they play an enormous role in river ecosystems.

“Each animal will filter 10 to 20 gallons of water a day, just like a Brita filter in your kitchen. They remove all these microscopic particles,” Kreeger said.

Mussels don’t only clean water, like trees do with air. They also provide food and housing for fish and other species, like coral reefs do in the ocean. And they can live for almost 100 years.

“They’re like conveyor belts — pulling material out of the water, cleaning the water, using some and enriching the bottom,” Kreeger said.

Hatchery’s aim includes cleaner water

Roger Thomas, a scientist at The Academy of Natural Sciences, says before the 1950s, mussels covered the Delaware River basin.

“The Schuylkill used to have mussels all the way to the headwaters. Now they’re gone,” Thomas said.

Mussel habitats got destroyed, rivers were contaminated and dammed — preventing the fish that would distribute them from reaching certain parts of the river — and people took too many of them, sometimes looking for pearls.

Kreeger said mussels may be in less than 5 percent of streams and tributaries in southeast Pennsylvania. Ten of about a dozen native species are in danger of disappearing.

“We’ve seen the range, the distribution, shrink. We’ve seen the numbers of animals drop. And in many of our remaining mussel beds, there is no natural reproduction going on; there are no juveniles to be found anywhere,” she said.

That is a big problem. Without a source of new mussels, it’s difficult for scientists to repopulate the river.

Last year, Philadelphia opened the exhibition mussel hatchery in the Water Works center, next to the Art Museum. And it’s been a good start. More than 25,000 visitors have learned about freshwater mussels and scientists have been able to successfully produce about 10,000 mussel seeds of two species.

Reid Frazier / StateImpact Pennsylvania

Biologist Lance Butler and Science Director Danielle Kreeger look at mussels and their larva to see if they are expelling viable larva known as Glochidia.

But Kreeger said the hatchery is too small. To repopulate the river beds and drastically improve water quality, she said the city needs a much bigger hatchery.

The new large-scale commercial hatchery, which will open sometime within the next three years, will produce about a million baby mussels every year. That will include the possibility of selling mussel seeds to populate and restore other areas of the watershed when needed.

But what will make this production hatchery unique in the world, Kreeger said, is that its goal is not only to preserve endangered mussels but to restore mussel beds to ultimately clean water.

“The possibility that mussel restoration will materially contribute to water quality and swimmable/fishable conditions is very plausible,” Kreeger said.

Mussels could be a money-saver for taxpayers

Lance Butler, a scientist with the Philadelphia Water Department working on the hatchery, said investing in mussels will also save taxpayers money. The city is already investing in gray and green infrastructure for water quality. By using living organisms, the Water Department is adding what Butler calls “blue infrastructure” to help them do the work.

Philadelphia gets drinking water from the Schuylkill and the Delaware rivers. Butler said if one mussel can filter 10 to 20 gallons of river water a day, imagine what tens of millions can do.

“They are doing the work for us, before the water comes in,” Butler said. “They are our ecosystems scrubbers. They are mini water waste treatment plants.”

A Philadelphia drinking water treatment facility cleans anywhere from 80 to 160 million gallons a day, so it would take 8 to 16 millions mussels to do their work. Butler is confident the bivalves — and their human colleagues at the hatchery— are up to the challenge.