‘The Shale Dilemma’ goes global: Author discusses shale gas development across the world

-

Reid Frazier/The Allegheny Front

Across Europe, laws on fracking vary. In 2016, after years of debate over environmental concerns and economic interests around fracking, Germany banned some forms of it. Environmentalists are calling for a total ban. Photo: Robin Wood / flickr” credit=”

Fracking may have been born in the U.S., but there are shale gas reserves in dozens of other countries. Will these countries say yes or no to fracking? Shanti Gamper-Rabindran a University of Pittsburgh professor and editor of The Shale Dilemma, sat down for an interview about the topic. The book examines decisions being made around the globe about fracking. Here are some highlights:

Q: What are the benefits and drawbacks of shale development countries are weighing?

A: In every country that is pursuing shale, the government generally states four different reasons why they pursue shale.

One is long term energy security. Second is broad-based economic development, not just economic development. Third is climate protection by shifting from coal to gas. And the fourth is air quality protection by switching from coal to gas at the point of combustion.

However, to achieve all these goals you need to have policies in place that ensure broad-based economic development. So the benefits of shale in Argentina and South Africa, for example, are not just to the recipients of cheaper energy. There is also some investment going back to the local community that bears most of the costs of shale production. Yes, it’s true that if you switch from coal to gas you would have better air quality at points of combustion, but if you don’t protect the local community at the point of production of shale, then they are now exposed to worse air quality.

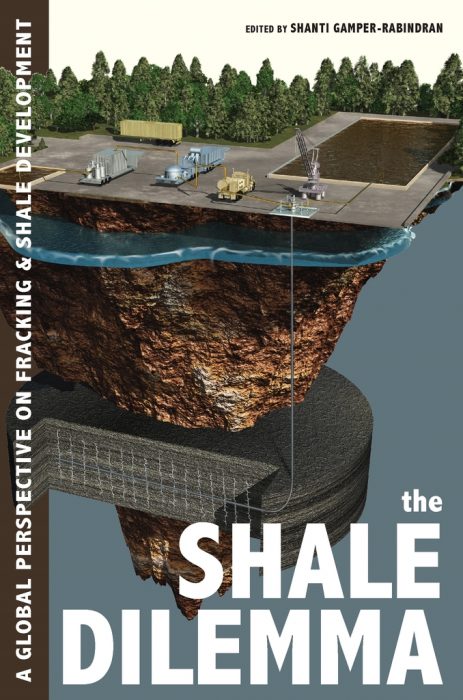

Published by University of Pittsburgh Press

Published by University of Pittsburgh Press

Q: What does “broad-based economic development” look like?

Take the case of some states in the United States. There are charges of severance taxes on oil and gas. The severance taxes go into permanent funds, which means funds are invested for the long term for people within the state.

So you can see that shale, although it could be owned by the private mineral rights owners through the severance tax, there is some form of transfer to the rest of the society. We also have shale extraction on public land so that royalty is also invested for the rest of the state.

Q: How does the U.S. stand apart in shale development?

In the U.S., we have two mechanisms that don’t exist in other countries that allow for broader economic distribution.

First, we’re less coupled with the world economy in terms of our natural gas. So when we have gas production, our gas prices fall and consumers in general benefit.

We have private mineral rights owners which means that the private owner gets benefits. However, the downside in the U.S. scheme is that private mineral right owners benefit, but the surface rights owners actually face the costs. At the moment, our laws very much favor mineral rights owners over surface owners. This is in a sense an equity issue because of surface owners are facing costs.

Q: How are other countries handling the shale dilemma?

France and Germany have decided not to pursue shale, and they are able to do this because they have other options in place.

In the case of France, they have reliance on nuclear and they are also investing heavily in a move from nuclear towards more renewable energy. They have been extremely diversified in their imports of natural gas. In those countries, we see a greater political space to debate the pros of shale and cons of shale. And given that they don’t have this immediate energy crisis at hand, they are able to take a wait and see approach.

In the case of Germany, it’s a moratorium. And in France, they’ve instituted a ban. They’ve bought this option value of time which is extremely valuable.

On the other hand, you see countries that have not invested in alternative energy resources as much as they need to. Argentina is highly dependent on conventional oil and gas and it’s fast declining. They are turning now to unconventional oil and gas in order to extract energy.

South Africa has not invested heavily in renewables as much as they could, although they have the physical capacity for very good solar and wind. So in those two countries you see an energy crisis and this desire to jump start the economy using shale.

We’ve seen that there is more of a push towards developing shale and less of an investment into the policies that you need to make sure that shale development results in broad-based economic development.