Scientists who feel under attack, to march for political clout

-

Susan Phillips

Kimberly Paynter / WHYY

Marion Leary with her daughter Harper making signs at Frankford Hall in Fishtown, ahead of Saturday’s March for Science in Philadelphia. Leary will be speaking at the rally about science communication, and hopes to get more researchers out of the lab and talking to the public.

Thousands of marchers are expected in Center City Philadelphia on Saturday for the first ever March for Science. The event is combined with the 47th annual Earth Day observance, which is expected to draw millions of people to cities and towns across the country, with the main event in Washington, D.C. Philadelphia’s demonstration will start at City Hall, with a march that ends up at Penn’s Landing. While this celebration of science is billed as nonpartisan, organizers say it’s time that scientists become a political force in an era when evidence based decision-making seems under attack.

Philadelphia’s original Earth Day organizers turned a day into a whole week of activism, teach-ins, and concerts in Fairmount Park. At the time, protest movements and college activism focused on stopping the war in Vietnam and promoting civil rights. The idea that hundreds of people would gather to promote environmental protection was novel.

Still people like Allen Ginsburg, Ralph Nadar and Dr. Benjamin Spock came to speak. The cast from the Broadway hit Hair showed up and performed. The events of that day had enormous impact on public policy. But marches have since become routine. It begs the question on what impact scientists and their supporters will have in the age of Trump.

Speaking to the crowd in Philadelphia on April 22, 1970, Dr. Benjamin Spock had a simple slogan:

“I want to say it for you. A better world for children, not just American children, for all children…that’s my program for Philadelphia, for the world. Thank you.”

It made enough of a splash to attract national attention. Walter Cronkite devoted a long feature on the Philadelphia events for his show on CBS.

“One of the biggest Earth Day observances was in Philadelphia where an estimated 20,000 to 40,000 persons gathered in perfect weather in the city’s largest park. It was an Earth Day success story,” Cronkite said in his opening lead to a nine-minute piece documenting Philadelphia’s organizing efforts and the city’s unchecked air and water pollution.

AP Photo

Earth Week crowd in Philadelphia, including, youngster wearing “Let Me Grow Up:” sign on back relaxes in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park Wednesday, April 23, 1970. Crowd made up mostly of young people, was estimated at more than 20,000 persons.

Getting Walter Cronkite to devote significant time on his show was a huge success for the organizers. And those first Earth Day events are credited with the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, and passage of the Clean Air Act, and the Clean Water Act.

Forty-seven years later, Philadelphia, like most major cities, doesn’t have incinerators belching out toxic smoke, there are restrictions on what the refineries can emit, and there are even fish starting to mate in the Delaware River for the first time in decades.

But today, scientists feel that factual research designed to solve problems and help people is under attack.

“Instead of evidence-based decision making, you just make up your own facts,” said researcher Sylvia Nuremberg, speaking at a sign-making party in Philadelphia ahead of the march. “And if we start with that, if that becomes the norm, what’s going to happen to us?”

Nuremberg, a research scientist, has never felt the need to march before. But like many of her fellow scientists, the events of the past several months have politicized her.

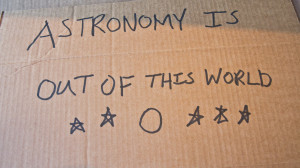

Kimberly Paynter / WHYY

A sign made ahead of the March for Science, which will take place in Philadelphia in conjunction with Earth Day on April 22, 2017.

Climate change, and the new Trump administration’s easy dismissal of it’s dangers, along with plans to de-fund the EPA and other scientific research has scientists like Nuremberg scared. It’s a novel thing for scientists to march.

Janice Rael hosted the sign-writing party at the Frankford Hall beer garden in Fishtown. With a hefeweizen beer in one hand, she’s wearing a molecular necklace.

“This is a molecule of caffeine,” said Rael pointing at her necklace. “I enjoy caffeine, I got a little science necklace, science earrings. Caffeine is one of my favorite chemicals.”

Rael says she expects 10,000 to 20,000 people to march in Philadelphia.

“I think with the cuts that are coming in the Trump Administration a lot more scientists are concerned and the general public is concerned as well. We’re trying to bring them together.”

But Rael knows a march won’t do much without continued organizing. So she works the room full of young volunteers making signs.

Jim Bergland, a PhD student at Temple University studying hydrogeology, is hard at work on his sign.

“It says ‘scientists don’t take the planet for granite’,” he explained. “It’s a bit of a pun. We’re geologists.”

Kimberly Paynter / WHYY

Janice Rael making her sign “Fund Science Research” in preparation for the March for Science on Saturday. Rael helped organize the Philly march.

Some scientists are critical of the march, worried it might backfire, or make scientists appear biased. This is an issue in the scientific community. But Bergland says he was inspired by the women’s march.

“We’re scientists so we try to be impartial because we want people to trust what we’re doing,” he said. “We’re out there collecting data and we want things to be objectifiable, but at some point as scientists, I think it’s ok to stand up and say ‘you know we need to be political about this.’ We need people to be well informed.”

But whether or not scientists can leave the lab and become a political force is still a question.

Richard Whiteford, a climate change activist and communicator is planning to take the train from Philadelphia to D.C. for the larger march in the nation’s capitol. Whiteford wonders what the long term impact could be.

“The march is valuable for visibility but what needs to happen is serious follow-up and serious pressure,” he said.

Whiteford says in some ways, the success of any demonstration is dependent on news coverage – but he says like everyone else, scientists can run for office, and they do have the power to boycott companies supporting the Trump Administration. His message to government scientists, those who work for NASA and NOAA is to go on strike.

“That’s real power,” he said.