Energy Hub vision challenged by Rinaldi's departure from PES

Newsworks

Sunoco Logistics plant in Marcus Hook, Delaware County. The site is undergoing construction to convert it from an oil refinery to a natural gas storage and processing plant.

The Philadelphia Energy Hub, a grand idea that was always longer on rhetoric than reality, took another step back this week when its leading advocate said he will retire early next year as chief executive of the East Coast’s biggest refiner, Philadelphia Energy Solutions.

Phil Rinaldi, dubbed “fossil Phil” by environmentalists for his aggressive promotion of Philadelphia as a major East Coast center for the transmission, storage and use of abundant natural gas from the Marcellus Shale, said he will step down in March but will stay on as head of the Greater Philadelphia Energy Action Team, the principal cheerleader for the Energy Hub.

The team’s spokespeople say it will continue to court investors in pipelines, storage tanks, processing plants and industries that would use natural gas and its associated liquids if they were pumped to Philadelphia in quantities that were large enough to allow the city to rival Houston as a regional energy center.

But two years after a closed-door meeting of potential investors at Drexel University failed to produce a desired surge in hub participants, Rinaldi’s coming departure from the helm of PES is renewing doubts about whether his vision will ever become a reality.

“The whole notion of the energy hub was always a lot of talk and a lot of PR,” said Matt Walker, community outreach director for the environmental group Clean Air Council, which opposes the project. “There were not a lot of specific proposals for projects that would make that into a reality, so with Phil Rinaldi retiring, and the lack of an obvious champion for the project, it’s going to lose a lot of steam.”

Some critics argue that the hub had already been killed by low energy prices which deterred investors and forced layoffs at Philadelphia Energy Solutions, the project’s primary driver.

Others say the hub’s boosters, including the Chamber of Commerce of Greater Philadelphia, squandered a chance to build city-wide support for the project when they failed to address the concerns of environmentalists, public health advocates, and some community leaders, fueling opponents who claimed the hub would make Philadelphia a “sacrifice zone” of dirty air, contaminated water and combustible oil trains.

“They lost the confidence of the public and a variety of very mobilized constituents to have what is often referred to as a social license – the confidence of people who are not directly benefiting but who are part of a city or region or state,” said Mark Alan Hughes, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy, which once played the role of honest broker between the hub’s advocates and other interest groups but has since stepped away from the project. “The failure of the Chamber’s vision to get their buy-in ultimately killed the project.”

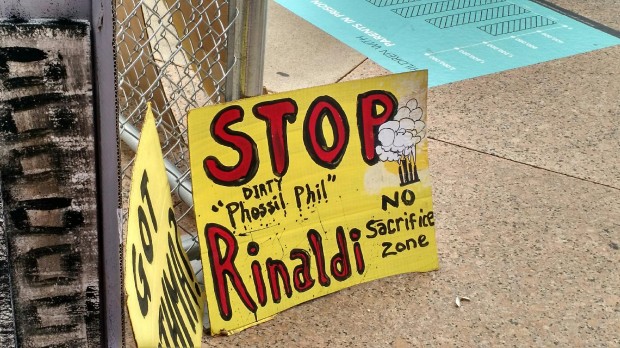

Katie Colaneri / WHYY

A protest sign targets Phil Rinaldi, CEO of the refinery Philadelphia Energy Solutions and visionary behind the Philadelphia "Energy Hub."

Opponents score some wins

Community qualms about the hub were amplified in late October when Philadelphia’s Democratic delegation to the Pennsylvania legislature urged the Philadelphia Regional Port Authority to reject plans for fossil fuel projects when selecting a developer for the Southport Marine Terminal.

Proposals for the site such as an oil-train terminal or a natural gas liquids facility would endanger public health by eroding air and water quality, and would contribute to climate change, the 18 lawmakers wrote in a letter that hub critics saw as an important reflection of public concern about the project.

Opponents cheered when the PRPA decided to use the land for the expansion of the Port of Philadelphia rather than selecting any competing bids such as a plan by PES for a crude oil import-export terminal.

Environmental groups that campaigned against any plan to use Southport for fossil fuel development said the PRPA’s decision was another nail in the coffin of the energy hub.

Walker of the Clean Air Council said the opposition from community groups played a role in the PRPA’s decision and has helped to deter investors.

“The opposition probably creates an unwelcoming atmosphere for potential investors or corporations thinking about locating here,” he said.

Little investor interest?

While there has been progress on some projects such as Sunoco’s Mariner East 1 and the Marcus Hook Industrial Complex that would contribute to the energy hub, there seems to have been little investor interest in the idea of a large-diameter pipeline to bring natural gas from the Marcellus to the Philadelphia area, as proposed by some advocates, Walker said.

Nat Hamilton/StateImpact Pennsylvania

CEO of Philadelphia Energy Solutions Phil Rinaldi and then Governor Tom Corbett watching the CSX train arrive supplying oil to the Philadelphia refinery.

In the meantime, Philadelphia Energy Solutions has fallen on hard times since Rinaldi arrived in 2012 and helped rescue the former Sunoco refinery when it was threatened with closure. Bakken shale oil from North Dakota, shipped on trains, breathed new life into the operation, saving hundreds of jobs. But Rinaldi’s attempts to take the company public in September failed, and layoffs followed.

Rinaldi, who denies human-caused climate change, failed to engage with the larger community over his vision for turning Philadelphia into the “Houston of the East,” according to Hughes.

Hughes says he believes the region could benefit from some aspects of Rinaldi’s Energy Hub vision, and that natural gas could be a bridge fuel to a clean energy future. But he blames Rinaldi and the Chamber for failing to listen to anyone with an alternative view of Philadelphia’s energy future.

“Its advocates were unyielding on things like climate denial,” said Hughes, “and what the [Energy Hub] vision is and the process that goes into putting the vision together. “Until there’s real change in that, I think it’s fair to say the energy hub is dead.”

For its part, the Energy Action Team argues that reports of the Hub’s death are greatly exaggerated.

‘Meaningful work’ to create hub

More than 100 companies and 170 individuals are now engaged in “meaningful work to develop the needed infrastructure,” said Erin Vizza, manager of team. She said the team is also supporting “priority projects” such as Mariner East 1 and the proposed Mariner East 2 natural gas liquids pipelines.

Vizza said Rinaldi’s retirement “will not affect our efforts” in light of the number of companies and volunteers contributing to the team.

She said 24 companies have contacted the team since its launch in 2013 to inquire about the availability of land and doing business in the Philadelphia region. She declined to name the companies, or specify the status of their plans relating to the hub, and acknowledged that the recent prolonged period of low energy prices had “slowed” inquiries from potential investors.

“We’ve seen a reasonably steady pace of energy-related projects,” she said.

Joe Ulrich / WITF

Fossil fuel infrastructure would become a more familiar sight in the Philadelphia region if the proposed energy hub becomes a reality.

Meanwhile, the team’s milestones include the publication in March of “A Pipeline for Growth”, a report outlining the energy hub vision, describing environmental safeguards, and discussing the economic growth that would come with the hub, Vizza said.

She also highlighted ongoing discussions with Pennsylvania officials and businesses about how to bring Marcellus gas to the Philadelphia region, and said hub advocates had recently joined City officials in a trip to Germany to discuss creating demand for natural gas among German manufacturers.

Vizza denied that investors have been discouraged by public opposition to current pipeline projects like Mariner East 2 and PennEast, and argued that critics can be won over by education about the economic benefits and environmental safety of such lines.

She declined to respond to Hughes’s claims that the hub idea has lost the support of the wider Philadelphia community, but argued that the project is “moving forward” with the support of civic and labor leaders such as Anthony Gallagher of Steamfitters Local 420 and Pat Eiding of the AFL CIO, both of whom are active team members, she said.

Cherice Corley, a spokeswoman for PES, said before Rinaldi’s retirement was announced that the company had contributed to the statement issued by the team but would have no further comment.

Support for the hub has also come recently from New Jersey Senate President Stephen Sweeney who talked up the project’s economic benefits for the Philadelphia-South Jersey region during a recent “South Jersey Road Show” by the team.

“Providing reliable, affordable sources of energy to the people and businesses of South Jersey is one of the most important things we can do to promote economic growth in our region,” Sweeney said in a statement.

Susan Phillips / StateImpact Pennsylvania

Protesters demonstrate outside of the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Old City Philadelphia, April 1, 2016. The Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce was meeting inside to discuss the energy hub.

In an apparent effort to raise the public profile of efforts to form the hub, Chamber of Commerce CEO Rob Wonderling wrote an op-ed piece in the Metro paper in late November, reiterating the economic benefits of the project and inviting readers to email him if they want to get involved in making the hub a reality.

That drew scorn from Kleinman’s Hughes who argued that the hub’s boosters were unlikely to garner more public support “unless there is a process that is more serious and more effective than that one.”

Wonderling’s piece, three weeks after the presidential election, may reflect the Chamber’s hopes that the incoming Trump administration will somehow breathe life into the hub process, Hughes said.

But even with a fossil fuel-friendly administration in Washington, hub advocates may face more public protests and legal challenges, and those circumstances are unlikely to help the investment climate, Hughes argued.

“Investors do not want the time delays in a region that lacks consensus, especially where there are alternative places to make investments, such as the Gulf Coast,” he said. “I think it’s a pipe dream that an old idea that was getting nowhere has suddenly got an investment-grade chance just because of the presidential election.”

Vizza said the Metro article coincides with team discussions about “new options for the facilitation of pipeline development.” She said the new options were related to a public-private partnership for pipeline development, but declined to be more specific.

In the end, the hub’s chances of becoming a reality will probably be determined by energy prices, argued John Quigley, a former head of Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection and now an independent energy analyst.

The recent rise in oil prices following OPEC’s production cut may foreshadow a more general increase in fossil fuel prices which would make a Philadelphia Energy Hub a more attractive proposition for investors, he said.

“I would think fossil fuel prices are going to start rising and that might bring some of the Energy Hub proposals back into the realm of viability,” Quigley said.